Mission

VSHD aims to help stabilize global population by securing women’s freedom to choose their family size. The purpose of this project is to transform girls’ lives by providing safe space clubs to adolescent girls in rural Niger, dramatically improving education outcomes and delaying marriage and childbearing.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

The Hausa is an ethnic group of 58 million deeply Islamic people living in several West African nations. Those living in southern Niger have one of the world’s highest rates of child marriage and maternal mortality and lowest rates of female literacy. More than 75 percent of girls marry before age 18, 30 percent before age 15, and more than 50 percent have their first child before their 18th birthday. Marriage has a dominant and pervasive position in the lives of the rural Hausa communities, as it is considered a safeguard against premarital sex and the primary avenue to secure a girl’s future childbearing within marriage.

Child marriage and childbearing: Child marriage has long-lasting consequences for girls’ health, education, income, and the development of agency and voice. It means early sexual activity and subsequently early childbearing. Hausa wives face social pressure to give birth during the first year of marriage. Married adolescent girls have significantly limited access to education because of restricted mobility and seclusion, household burdens, childbearing, and childrearing. These girls face disadvantages over a wide range of welfare indicators including health, education, and labor force participation. This has a direct impact on the broader social and economic development of Niger.

Child marriage and childbearing: Child marriage has long-lasting consequences for girls’ health, education, income, and the development of agency and voice. It means early sexual activity and subsequently early childbearing. Hausa wives face social pressure to give birth during the first year of marriage. Married adolescent girls have significantly limited access to education because of restricted mobility and seclusion, household burdens, childbearing, and childrearing. These girls face disadvantages over a wide range of welfare indicators including health, education, and labor force participation. This has a direct impact on the broader social and economic development of Niger.

Married adolescents are up to five times more likely to die from complications of pregnancy and childbirth than women in their twenties, and they are more likely to suffer from prolonged or obstructed labor and obstetric fistula. Adolescent brides are also less likely to receive proper medical care during pregnancy and delivery. Complications of pregnancy and childbirth are among the leading causes of mortality and morbidity for adolescent girls in developing countries. Child marriage also has consequences for the girls’ children: infants of adolescent mothers are 60 percent more likely to die and 20 percent more likely to be born preterm and with low birth weight compared to infants born to young women.

Seclusion and lack of quality education: Virtually all rural Hausa families practice a system of seclusion in which married women are expected to conduct most activities within their compounds and other private spaces. A woman needs t he permission of the head of household to go outside the home to visit a relative or a health facility, even in the case of an emergency. With such limitations on work outside the home, women engage in a variety of economic activities in their courtyards such as sewing and preparing products for sale. Girls assist their mothers by going to the market, hawking foodstuffs, fetching water, and minding younger siblings. As a result, mothers are often uninterested in keeping a daughter in school. Girls typically drop out of school when they get married. This limited exposure to school has an impact not only on their future earnings but also on the number of children they will bear and how healthy their children will be.

he permission of the head of household to go outside the home to visit a relative or a health facility, even in the case of an emergency. With such limitations on work outside the home, women engage in a variety of economic activities in their courtyards such as sewing and preparing products for sale. Girls assist their mothers by going to the market, hawking foodstuffs, fetching water, and minding younger siblings. As a result, mothers are often uninterested in keeping a daughter in school. Girls typically drop out of school when they get married. This limited exposure to school has an impact not only on their future earnings but also on the number of children they will bear and how healthy their children will be.

Parents in rural Niger are forced to make tough choices. Rural public education suffers from a lack of qualified teachers, decaying infrastructure, and limited funding – all of which contribute to poor learning outcomes. Rural government schools are of such poor quality that it is not unusual for a child to graduate from primary school without learning to read and write. Parents complain that the investment in uniforms, levies, transport, snacks and the opportunity costs of losing their daughters’ labor are hardly worth the poor learning outcomes they see.

There are three primary drivers of child marriage:

- Poverty

: Child marriage occurs most frequently among the girls who are the poorest, least educated, and living in rural areas. Girls from households in the poorest quintile are almost twice as likely to marry before the age of 18 compared with those from households in the wealthiest quintile. The same is true for rural girls compared to urban. When a daughter reaches puberty, the poorest families will attempt to find her a husband rather than keep her in school, because schooling presents both high fees and opportunity costs.

: Child marriage occurs most frequently among the girls who are the poorest, least educated, and living in rural areas. Girls from households in the poorest quintile are almost twice as likely to marry before the age of 18 compared with those from households in the wealthiest quintile. The same is true for rural girls compared to urban. When a daughter reaches puberty, the poorest families will attempt to find her a husband rather than keep her in school, because schooling presents both high fees and opportunity costs. - Social norms: In much of the Sahel, marriage-related decision making is usually a communal process. Once a girl has started menstruation, fears of non-marital sexual activity and pregnancy become a major concern for parents. The parents of an older adolescent girl who remains unmarried can experience community pressure to get her married before she “brings shame” upon the family and community.

- Lack of socially viable alternatives, especially in rural settings: Schooling is the most socially viable alternative to child marriage. Parents know that school can lead to highly valued employment as teachers and government employees and can bring a number of other benefits. They say that children who have attended school are more composed and that one can immediately tell that they are educated. Yet, in Niger, only 44 percent of girls are enrolled in primary school and even less (14 percent) are in secondary school. For every 100 boys enrolled in primary school, there are only 80 girls, and in secondary school, only 70 girls. The situation is worse in rural communities where girls are twice as likely to be out of school as those from urban areas.

Niger’s population of 20.7 million people is growing at almost 4 percent a year—one of the highest rates in the world, with a total fertility rate of 7.6 children per woman. There will be triple the number of people in the nation in just 30 years if this pattern continues. This unparalleled growth could overwhelm improvements in education and health.

The Project

The Pathways to Choice project encourages girls in rural Niger to stay in school and delay marriage and childbearing. This grant allows VSHD to bring the Pathways to Choice program from Nigeria to rural Hausa girls in Maradi, Niger, where the culture and language is the same but the situation is even more challenging. The Pathways to Choice Initiative dramatically improves the lives of rural girls ages 12 – 14 by increasing core academic skills, which promotes their transition from primary to secondary school, a time of risk for withdrawal and early marriage. The Pathways Initiative will serve as a girls’ education learning hub for southern Niger.

The Pathways to Choice project encourages girls in rural Niger to stay in school and delay marriage and childbearing. This grant allows VSHD to bring the Pathways to Choice program from Nigeria to rural Hausa girls in Maradi, Niger, where the culture and language is the same but the situation is even more challenging. The Pathways to Choice Initiative dramatically improves the lives of rural girls ages 12 – 14 by increasing core academic skills, which promotes their transition from primary to secondary school, a time of risk for withdrawal and early marriage. The Pathways Initiative will serve as a girls’ education learning hub for southern Niger.

The project combines two highly successful programs that offer on-the-ground safe spaces to adolescent girls: the Oasis Initiative (OASIS) and the Centre for Girls Education (CGE). CGE is a nongovernmental organization that provides safe, mentored after-school locations and the Oasis Initiative (Organizing to Advance Solutions in the Sahel) is a VSHD program that helps accelerate demographic change in the Sahel. VSHD oversees OASIS Niger and the Centre for Girls Education, and these will act as a single implementing body for the Pathways Initiative.

The dynamics underlying early marriage are so pervasive that interventions meant to enhance the viability of alternatives must provide clear and tangible benefits that are valued by parents and daughters. VSHD’s methodology is both practical and best suited to the rural Hausa girls. The program design and the theory of change underlying it evolved over 10 years of careful community-based research with rural girls, their mothers, fathers, community members, and religious leaders by the Centre for Girls Education in Nigeria, and more recently, by OASIS in Niger. The Pathways initiative was designed to address parents’ and daughters’ concerns about poor educational outcomes and other issues and builds on the work of the Centre for Girls Education.

The Pathways to Choice program has already seen great success in rural Nigeria: after two years in the program, girls’ secondary school graduation rate increased twentyfold and the age of marriage increased by 2.5 years. These 2.5 years are a critical time in a young girl’s life when she can further develop physically and emotionally, gain a greater sense of self, and acquire the skills that allow her to live the life to which she aspires.

The Pathways to Choice program has already seen great success in rural Nigeria: after two years in the program, girls’ secondary school graduation rate increased twentyfold and the age of marriage increased by 2.5 years. These 2.5 years are a critical time in a young girl’s life when she can further develop physically and emotionally, gain a greater sense of self, and acquire the skills that allow her to live the life to which she aspires.

Six years or more of girls’ schooling is associated with delayed marriage, improved use of prenatal care and delivery services, and increased contraceptive use. If all girls in Sub-Saharan Africa were to complete primary school, 113,400 maternal deaths would be prevented each year. If all were to complete secondary school the number of child marriages would fall by 64 percent. Girls’ secondary education reduces poverty, stimulates economic growth, and helps women realize their fundamental human rights.

The objectives of this program are to:

- Quadruple participating rural girls’ junior secondary school completion rates

- Dramatically enhance girls’ aspirations, agency, and voice

- Delay marriage by at least 2.5 years

- Improve effectiveness of rural female teachers

- Increase community support for girls’ education and delayed marriage

- Increase local and provincial governmental stakeholder support and ownership of project.

The core components of the Pathways Initiative include focused community engagement, mentored girls’ clubs (safe spaces), and capacity building activities for the female teachers who lead the clubs. Safe spaces – a safe place, friends, and a mentor – is the heart of the program. VSHD has adapted the safe space methodology to meet girls’ need for strengthened core academic competencies, particularly reading and writing, and mentored support. The safe spaces are organized after class in the girls’ own schools and are led by female teachers trained in group facilitation, interactive teaching methods, accelerated literacy instruction, reproductive health, and gender equity. Pathways to Choice works in the poorest parts of the poorest countries in the world. They recruit all the girls in the last year of primary school at participating schools. VSHD’s experience is that including all the girls, instead of just those who stand out, is the most effective way to facilitate change in a community.

The core components of the Pathways Initiative include focused community engagement, mentored girls’ clubs (safe spaces), and capacity building activities for the female teachers who lead the clubs. Safe spaces – a safe place, friends, and a mentor – is the heart of the program. VSHD has adapted the safe space methodology to meet girls’ need for strengthened core academic competencies, particularly reading and writing, and mentored support. The safe spaces are organized after class in the girls’ own schools and are led by female teachers trained in group facilitation, interactive teaching methods, accelerated literacy instruction, reproductive health, and gender equity. Pathways to Choice works in the poorest parts of the poorest countries in the world. They recruit all the girls in the last year of primary school at participating schools. VSHD’s experience is that including all the girls, instead of just those who stand out, is the most effective way to facilitate change in a community.

The three key components of the project are:

1. Focused Community Engagement

Pathways is introduced to the communities through a series of discussions with groups of traditional and religious leaders, women, men, teachers, and informal leaders. Religious leaders from clusters of communities are convened to examine support in the Qur’an and Hadith for girls’ education and to carefully review the safe space curriculum with them. Once consensus is attained, community meetings are organized in each location to review and agree on the key conclusions from the group discussions and the key components of the girls’ education program.

2. Safe Spaces

2. Safe Spaces

Safe spaces are the backbone of the program. Typically used as an alternative, non-formal approach to educating adolescent girls who are not in school, VSHD has adapted the safe space methodology to meet school girls’ need for strengthened core academic competencies and mentored support as they address the challenges encountered in secondary school. Girls’ participation in the safe spaces greatly enhances their literacy and numeracy skills and provides opportunities to gain crucial reproductive health information and life skills not offered in secondary school.

3. Enhanced capacity of female teachers

The safe spaces are organized after class in the girls’ own schools and are led by female teachers trained by the Pathways’ team in group facilitation, interactive teaching methods, accelerated methods for literacy, adolescent reproductive health, and gender equity. The presence of female teachers has been shown to increase girls’ enrollment, retention, and learning outcomes. Female teachers can advocate for girls, represent their perspectives, and may increase protection from sexual harassment, abuse and exploitation. In addition, the Centre has documented female teachers’ use of the teaching methods they learn as mentors in their own school classrooms.

The Pathways for Choice initiative will recruit 700 adolescent girls ages 12 – 14 residing in rural communities in Maradi. Nearly all participants will be from farming families with incomes below one dollar a day. Nearly all of the people impacted will be women and girls. Adolescent girls who participate in safe spaces teach what they learn to younger siblings. These same girls are then recruited as safe space mentors and go on to impact even more girls, in safe spaces and beyond.

Pathways will indirectly impact rural children of a range of ages and backgrounds. In Hausa communities, the older children, especially daughters, are expected to care for their younger siblings. Research shows that a majority of the girls in the safe spaces pass on what they are learning (especially literacy and life skills) to their younger siblings. The inhabitants of rural southern Niger have large families, with a typical adolescent girl caring for three siblings on average. With 700 participating girls, the estimate is that 2,100 younger siblings will indirectly benefit from the program (one half of them girls). In addition, research shows that the girls in the safe spaces are extremely effective advocates for girls’ education.

Neighbors and community members report being impressed by the girls’ composure and ability to express what they want in a respectful manner. Norms change as more and more parents enroll their girls in school. Pathways will conduct 39 clubs with 18 participating girls in each. VSHD estimates that for every girl in a safe space club, five families are encouraged to enroll their daughters in school following successful implementation of safe spaces in their community.

Year 1 direct impact: 250; indirect impact: 1,638

Year 2 direct impact: 450; indirect impact: 2,925

UN Global Goals for Sustainable Development

![]()

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- Why is it important that all girls be offered this program in participating schools?

- What changes might occur over time for the girls’ parents?

- What kind of outcomes do you think might convince Niger’s government to adopt these educational practices?

How the Grant Will be Used

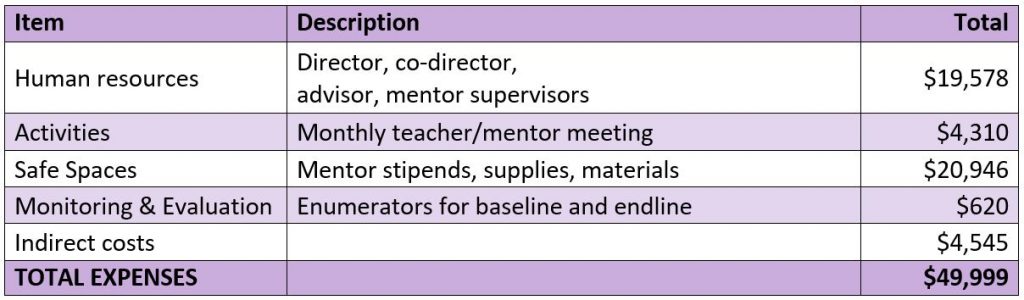

DFW’s grant of $49,999 will be used for the following:

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love this project, which is grounded in proven field-tested methodologies with its focus on vulnerable, isolated rural adolescent girls of the Hausa minority in rural Niger. This project involves the entire community in supporting safe spaces for adolescent girls to develop leadership skills, gain knowledge about reproductive health, and be mentored to continue their education and increase their self-confidence and self-esteem.

Evidence of Success

As an organization, VSHD has been making steady progress towards building the evidence base for family planning, girls’ education, and women’s empowerment as key levers for sustainable development in the Sahel. VSHD believes that sustainable solutions in the Sahel are best conceived, implemented, and scaled up by local people. VSHD has trained more than 150 emerging leaders in a vast array of topics, including research methods, demography, and program design.

The Centre’s northern Nigerian mentored girls’ clubs (safe spaces) have been remarkably successful. At baseline in 2007, only 4 percent of girls graduating from primary school in participating communities went on to graduate from senior secondary. Of the first 1,000 girls attending the Centre’s safe spaces, 82 percent graduated from secondary school. The age of marriage increased by 2.5 years – from 14.9 to 17.4. The Centre’s safe spaces provide intensive literacy and numeracy training. Girls who have spent years in primary school without even learning to read are now literate.

The Centre’s northern Nigerian mentored girls’ clubs (safe spaces) have been remarkably successful. At baseline in 2007, only 4 percent of girls graduating from primary school in participating communities went on to graduate from senior secondary. Of the first 1,000 girls attending the Centre’s safe spaces, 82 percent graduated from secondary school. The age of marriage increased by 2.5 years – from 14.9 to 17.4. The Centre’s safe spaces provide intensive literacy and numeracy training. Girls who have spent years in primary school without even learning to read are now literate.

Venture Strategies for Health and Development has received numerous accolades:

- VSHD was recognized as the top organization of the 2018 Unfunded List competition.

- The Malala Fund, founded by Malala Yousafzai, has awarded Habiba Mohammed, Co-Director, a Gulmakai Fellowship in recognition of her two decades of work enhancing girls’ education.

- Malala Yousafzai has visited Nigeria and met with the Centre’s staff and participating girls two times, and invited one of the girls, Amina Yusuf, to attend her Nobel Peace Prize award ceremony to represent the 66 million girls who are out of school globally. Amina is now on the Centre’s full-time staff.

- The Centre has been shortlisted for the 2018 WISE Award by the World Innovation Summit for Education.

Voices of the Girls

“What is the use of six years of schooling if you give your child a book to read and all she does is stammer? We think of all we go through to keep our children in school and yet with nothing to show for it. It is better to withdraw your girl from school and marry her off.”

“What is the use of six years of schooling if you give your child a book to read and all she does is stammer? We think of all we go through to keep our children in school and yet with nothing to show for it. It is better to withdraw your girl from school and marry her off.”

- A mother in rural Niger

“If a girl is getting a quality education her mind will be occupied with school and she won’t have time to spend with boys.”

- A mother in rural Niger

“A school girl lives in the house where I stay. Her aunt told me that she would be removed from school soon. ‘She’s in secondary school and can’t read a word,’ she said. I asked why this is so. She said they don’t teach them in school and the women in the house have little education and are unable to help. They themselves would like to attend adult education classes and learn to read and write.”

- From a researcher’s field diary

“You could say the girls are being reeducated in the fundamentals that they were taught in school but never learned,” said one father. “The mentors sit them down and teach the girls in a practical way, and when they get back home, they share what they learn with their siblings.”

- Father of Centre for Girls Education participant

“They say a book is a weapon against illiteracy and poverty. It liberates a nation and makes the world a better place. My safe space gave me knowledge of adolescent issues, among many other things, and what I learned helps me become a better mentor to the younger girls.”

- A former safe space participant

About the Organization

Venture Strategies for Health and Development (VSHD) was founded in 2002 by Martha Campbell at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Public Health. Alisha Graves is the current president. In 2003, VSHD launched a program to promote misoprostol availability for the prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in developing countries. Their international advocacy work has grown to include family planning, women’s health, and girls’ education. Following these successes, VSHD widened its scope to work with local partners and helped found and oversee OASIS Niger (Organizing to Advance Solutions in the Sahel) and the Centre for Girls Education (Centre, CGE), in rural Niger and Nigeria, respectively.

Venture Strategies for Health and Development (VSHD) was founded in 2002 by Martha Campbell at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Public Health. Alisha Graves is the current president. In 2003, VSHD launched a program to promote misoprostol availability for the prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage in developing countries. Their international advocacy work has grown to include family planning, women’s health, and girls’ education. Following these successes, VSHD widened its scope to work with local partners and helped found and oversee OASIS Niger (Organizing to Advance Solutions in the Sahel) and the Centre for Girls Education (Centre, CGE), in rural Niger and Nigeria, respectively.

The Sahel Leadership program works with mid-career professionals from Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, Cote D’Ivoire, and Benin in the fields of girls’ education, empowerment, and family planning. The Women in Development program trains female graduate students in research methods and program design in Niger. The Room to Grow project engages rural women who work in women-led gardens in Niger.

The Centre for Girls Education, led by Habiba Mohammed, is registered as an indigenous non-governmental organization in Nigeria, and has been a close partner of VSHD from its founding in 2006. The Centre has been an innovator in safe space (mentored girls’ clubs) design, implementation, and evaluation in northern Nigeria since its inception. The Centre conducts operations research in partnership with the University of California, Berkeley on the effectiveness of educational strategies, both formal and informal, in improving adolescent girls’ lives and, more specifically, maternal and child health outcomes in the region.

Safe Spaces is an intervention designed around mentored groups proven to delay marriage by keeping girls in school. Teenage girls connect with peers, gain life skills and bridge gaps in academic learning, particularly reading and writing. The Centre has implemented Safe Spaces with more than 20,000 girls ages 8 – 18, in rural areas in four northern Nigeria states. The girls range in education attainment from those in school, to out-of-school, to married adolescents. It has also hosted five UNFPA sponsored delegations from Sahelian nations, is the subject of five training films on girls’ education by the World Bank, and has trained staff from numerous national and international governmental and non-governmental organizations. The Centre for Girls Education currently serves 20,000 girls,

Safe Spaces is an intervention designed around mentored groups proven to delay marriage by keeping girls in school. Teenage girls connect with peers, gain life skills and bridge gaps in academic learning, particularly reading and writing. The Centre has implemented Safe Spaces with more than 20,000 girls ages 8 – 18, in rural areas in four northern Nigeria states. The girls range in education attainment from those in school, to out-of-school, to married adolescents. It has also hosted five UNFPA sponsored delegations from Sahelian nations, is the subject of five training films on girls’ education by the World Bank, and has trained staff from numerous national and international governmental and non-governmental organizations. The Centre for Girls Education currently serves 20,000 girls,

OASIS Niger is a recognized civil society organization in Niger and addresses the most serious challenges to women and girls’ welfare in the Sahel region of Africa. OASIS has conducted extensive operations research (including anthropological research on child marriage and women and girls’ health and capacity building) in the Maradi, Niger, region for the past three years. These studies have laid the groundwork for VSHD’s expansion of the Centre’s groundbreaking program to Maradi in southern Niger. The Sahel Leadership Program is catalyzing a critical mass of emerging leaders dedicated to women’s empowerment and family planning, and the Women in Development Fellowship attracts Nigerien graduate students to the field of population, family planning, and empowerment.

Southern Niger has not experienced the level of civil conflict found in northeastern Nigeria, which is at the center of the Boko Haram insurgency and the location of the abduction of over 200 girls in Chibok. However, there has been some violence near Niger’s borders with Nigeria and Mali. Despite these challenges, the Centre’s work in northern Nigerian communities continues to be well received and the Centre has thrived, as has OASIS Niger’s research in the Maradi region of southern Niger. The fact that the two organizations overcame such challenges and built a strong base for their programs reflects the quality of their staff. In the same way, the Pathways program in Maradi will employ local women as mentors and outreach staff. Though insecurity does present an ongoing risk, the experienced staff works to mitigate this risk by implementing the program in a culturally sensitive manner and by consulting regularly with parents and community leaders. The world’s lowest rates of girls’ school enrolment and highest rates of child marriage are found in regions that are experiencing social unrest, and if this is to be addressed, it is necessary to work in areas where it is occurring.

Where They Work

VSHD focuses on the Sahel region of Africa. Local offices are in Niger’s capital city of Niamey (OASIS Niger) and in Zaria, Nigeria (Centre for Girls Education).

Africa’s Sahel is a large semi-arid swath more than 600 miles wide that goes from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, the dividing line between the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. To the north is Arabic, Islamic, and nomadic cultures, and to the south are indigenous and traditional cultures. The northern portion is hot, dry desert, while the southern portion has more tropical areas. Both regions of the Sahel are challenged by ethno-religious tensions, political instability, poverty, and natural disasters.

Niger is a landlocked country situated on the northern side of the Sahel, with 80 percent in the Sahara Desert. It is the size of France and home to 19 million people. Although the official language is French, there are about 20 indigenous languages spoken. Life in Niger is challenging, due to the desert terrain, lack of education and healthcare, and poverty. In dry years, there is typically not enough food to go around. When drought strikes, nomadic families often lose entire herds of sheep, cattle, and camels. Niger has the highest fertility rate in the world (average 7.6 children) and one of the lowest average incomes ($427 per year). Only 18 percent are enrolled in secondary school – the second lowest percentage in the world – which is one of the key reasons why just 19 percent are literate. Only 11 percent of women in Niger are literate, as girls only stay in school an average of three years.

A closer look at the benefits of safe spaces for girls

We take after-school and other youth programs for granted, worrying that our young daughters are “over scheduled” in the afternoon. But that isn’t the case around the world. Today, as the average age on the planet grows younger, fewer girls have access to an adequate education or guidance, much less a place to go after school. Many carry a heavy burden of responsibility, caring for younger siblings or other family members.

Safe spaces usually mean girls-only meeting places, and they are an important way to help girls develop positive relationships and talk through issues that are otherwise often off limits at home. The key here is that these gathering places emphasize a sense of community versus individuality – which is unlike what we experience in our Western culture.

Safe spaces usually mean girls-only meeting places, and they are an important way to help girls develop positive relationships and talk through issues that are otherwise often off limits at home. The key here is that these gathering places emphasize a sense of community versus individuality – which is unlike what we experience in our Western culture.

After-school groups and clubs are a way for girls to connect on a whole new level. Researchers have found that girls’ clubs that include a time for self-reflection and questioning the status quo help combat discriminatory and oppressive gender norms. This is especially the case when the questioning is led by trained female mentors who create a welcoming and safe environment for honest reflection. Researchers have found that girls exposed to this kind of environment experience positive changes in attitude and are more likely to report incidences of violence compared to girls who did not participate. Opening up a dialogue about sensitive issues such as sex and relationships requires a skilled, female leader, preferably one who is an integral part of an already-established school or community group rather than an outsider who is unknown.

Most of us can remember a teacher or older friend who left an impression. A positive, uplifting mentor can have a profound effect on a young girl living in poverty. Sometimes it can mean the difference between a life of grief and a path to success. Data confirms that giving girls a chance to rise out of abject conditions often starts with education – and that education often includes a safe space where a girl can open up about the inherent difficulties in her life.

Source Materials

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/whatworksingirlseducation1.pdf

https://www.devex.com/news/opinion-safe-spaces-can-unlock-girls-potential-when-we-get-it-right-93259

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ng.html

http://theconversation.com/sahel-region-africa-72569

http://rain4sahara.org/about-rain/niger-facts