Mission

African Women Rising empowers women after war by providing self-sustaining solutions that give hope and change lives.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

Women and girls in developing countries who have experienced the horrors of war face a grueling future. Many are widows and orphans, girl mothers, formerly abducted, raped, tortured, and HIV-positive. They are largely uneducated, poor, and often ostracized from their communities. The most vulnerable typically have the least access to support or social services, thus rebuilding their lives or reintegrating back into their communities becomes almost impossible. Most are left destitute and hungry.

South Sudan’s 22-year civil war is a clear example. According to recent data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), ten months after fresh violence erupted in South Sudan, a growing famine produced by the vicious combination of fighting and drought is driving the world’s fastest growing refugee crisis. Total displacement from South Sudan is now 1.6 million people. The rate of new displacement is alarming, creating a burden for countries in the region that are significantly poorer and quickly running out of resources.

After enduring unspeakable cruelties, 95 percent of the South Sudanese have been forced to live in camps for the internally displaced. At least 50,000 people have died, 100,000 are suffering famine, and 1,000,000 are on the brink of starvation. Almost half of these refugees are crossing the border into Uganda to escape the fighting and to search for food and security. Today, Uganda hosts over 900,000 refugees from South Sudan. The majority – over 64 percent – are children under age 18. Together with women, they make up 86 percent of the refugee population in Uganda.

The situation is critical in Uganda’s northern region, where until recently, new arrivals were arriving at a rate of almost 2,000 people daily. The influx peaked in February 2017 at more than 6,000 in a single day. Transit facilities created to deal with the newly arriving refugees from South Sudan are becoming overwhelmed. Recent rains in the area have also not helped matters and are adding to the difficulties in relocating the refugees and providing adequate services within the newly opened camps that serve them.

The situation is critical in Uganda’s northern region, where until recently, new arrivals were arriving at a rate of almost 2,000 people daily. The influx peaked in February 2017 at more than 6,000 in a single day. Transit facilities created to deal with the newly arriving refugees from South Sudan are becoming overwhelmed. Recent rains in the area have also not helped matters and are adding to the difficulties in relocating the refugees and providing adequate services within the newly opened camps that serve them.

Access to food is a key challenge faced by the newly arrived refugees. Due to lack of resources, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has limited rations and cannot guarantee long term adequate food supplies for the refugees. In addition to concerns about the health of the starving refugees, experts fear the food shortage could spark tensions between the people living in host villages and the refugee communities who have nowhere else to go – and nothing to eat.

Even without the refugees, 80 percent of the population in Northern Uganda relies on subsistence farming. These individuals depend on food from their gardens and resources from the broader environment for firewood, medicine, building materials, and fodder for their animals. As smallholder farmers, they consume much of what they grow. At harvest, their yields are often only seven months’ worth of food. Even with improved yields, food insecurity and potential hunger still remain. Households then buy, trade, or barter for food (often at higher costs later in the season) or cut down on meals to once a day or every other day.

The Acholi region of Northern Uganda is one of the most food insecure regions in the country. In addition to the 600,000+ Ugandans living in Acholi land, an additional 50,000 South Sudanese refugees are expected to be living in a camp recently established. UNHCR has requested $501 million to support refugees in Uganda but only received 15 percent. Access to food remains a major concern. Even as peace has come to the region and more land has been put into cultivation, seasonal hunger gaps remain a persistent problem. Severe climatic fluctuations in recent years have affected field crop production. Since the conflict ended in 2007, unseasonal floods and intra-seasonal drought have kept yields lower than anticipated.

Another related challenge is the lack of access to agricultural land. In conjunction with the Ugandan Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), refugees have been allocated 30 x 30 meter plots of land from which they are expected to feed their families. The small amount of land is further compounded by the unpredictable changes in the climate and weather patterns. Rains have become more erratic and unevenly distributed throughout the growing season. These environmental pressures require innovative agricultural interventions that can ensure food production continues on these small plots amidst harsh climatic conditions.

The reason tens of thousands of refugees from South Sudan have not received the support they need is because the government of Uganda, as well as the UN agencies and NGOs, face a massive shortfall in funding, despite international appeals for help.

The Project

Dining for Women’s grant allows Africa Women Rising (AWR) to help Ugandans and South Sudanese Refugees (mostly women) in Uganda’s Acholi region become more self-sufficient and able to provide food for themselves and their families. AWR’s Permagarden Program ensures year-round access to vegetables and fruit through the establishment of small home vegetable gardens. The ability to grow their own food gives women confidence and freedom to pursue higher goals. Often, they can sell excess yields to supplement their incomes and send their children to school or access health care. Only when this basic need for food is fulfilled can families pursue higher goals such as literacy and economic stability.

More than “kitchen gardens,” permagardens are based on the appropriate use of local resources, water conservation and long-term soil fertility measures to produce a variety of nutritious and accessible food crops. The program draws from best practices and lessons learned from thousands of permaculture and biointensive gardening projects around the world. These practices include interventions that can mitigate the impacts of climate change such as fluctuations in temperature and rainfall. Permagardens work hand-in-hand with field crops as an insurance policy against crop failure. Households and communities are able to control the water, nutrients, and care far more than in field crops, and have the potential to produce abundant crops year-round. With households depending on their own primary food sources, it is all the more important to focus on improved yields at the household level.

More than “kitchen gardens,” permagardens are based on the appropriate use of local resources, water conservation and long-term soil fertility measures to produce a variety of nutritious and accessible food crops. The program draws from best practices and lessons learned from thousands of permaculture and biointensive gardening projects around the world. These practices include interventions that can mitigate the impacts of climate change such as fluctuations in temperature and rainfall. Permagardens work hand-in-hand with field crops as an insurance policy against crop failure. Households and communities are able to control the water, nutrients, and care far more than in field crops, and have the potential to produce abundant crops year-round. With households depending on their own primary food sources, it is all the more important to focus on improved yields at the household level.

The one-year Permagarden Program will serve 400 individuals directly and 2,800 indirectly, since the average woman has seven dependents (her own children and, often, orphans). Participants will be recruited and organized through community meetings and through AWR’s existing microfinance groups and literacy programs. Ninety percent are expected to be women and 75 percent Sudanese refugees. The goal of the program is for 85 percent, or 340, of these 400 participants to establish permagardens, enjoy improved food security, adopt at least three productive practices (such as composting, crop rotation, and fencing) and utilize beneficial water and soil conservation measures. To achieve this, AWR has a proven method that combines outreach, training, monitoring, and exchange visits.

- Outreach: Community Mobilizers hold community meetings to inform women about the Permagarden Program and recruit them into the program. Groups identified as having high food insecurity (refugees) are prioritized for the program.

- Training: The training consists of three-day intensive hands-on workshops held three times per year (every four months). Sessions are held at different homesteads within the community and selected by the group. Approximately 25 to 30 individuals participate in each of the 10 training modules that cover:

- Community resource walk and landscape mapping

- Water harvesting and control

- Biointensive soil preparation

- Planting techniques and management

- Water conservation

- Composting

- Botanical pesticides and fungicides and liquid fertilizers

- Organic materials, fertilizers and soil amendments sourced in the community

- Garden protection and upkeep

- Monitoring: AWR conducts a baseline assessment at the start of each program that includes income level and assets, access to land or other natural resources, number of children and how many are in school, health issues (including whether they are HIV-positive) and literacy level. Another assessment is made one year later to see what has changed. In addition, local Community Mobilizers receive ongoing feedback from the groups they interact with weekly. An Agricultural Extension Agent conducts bi-monthly visits to provide technical support. Data is captured in AWR’s permagarden Monthly Monitoring Survey, a mix of quantitative and qualitative measures. The results are compiled and aggregated on an annual basis to measure overall program performance.

- Exchange Visits: Participants visit other permagarden sites as well as a local commercial organic agricultural production site during the year. Having participants see a functional permagarden drastically increases the success rate.

Benefits of the program include increased soil fertility, enhanced crop yields, healthier diet and nutrition, more income for participants, and better access to healthcare and schooling. The primary indicator used to measure success is the average number of Months of Adequate Household Food Provisioning (MAHFP). It is measured through annual quantitative household surveys, and forms part of the baseline information gathered when AWR begins working with participants. Participants are re-assessed yearly as long as they remain in the program.

Benefits of the program include increased soil fertility, enhanced crop yields, healthier diet and nutrition, more income for participants, and better access to healthcare and schooling. The primary indicator used to measure success is the average number of Months of Adequate Household Food Provisioning (MAHFP). It is measured through annual quantitative household surveys, and forms part of the baseline information gathered when AWR begins working with participants. Participants are re-assessed yearly as long as they remain in the program.

The Permagarden Program was developed from discussions with women who were experiencing hunger. Program participants decide where and when the trainings will take place and choose the host farmer. The host farmer is a participant who attends the instructor training alongside AWR’s other Community Mobilizers and on whose homestead the permagarden trainings take place. The host farmer serves as a leader for the group. Many host farmers end up becoming employed with AWR and work as Community Mobilizers.

The Permagarden Program has been well received. As a result, there is more interest than there is funding. Several local government officials have asked AWR to work in their sub-counties. While participants are able to continue on their own after completion of the program, it is highly unlikely the program will reach a point of self-sufficiency. The long-term vision is to build a cadre of permagarden trainers who can help other organizations implement this kind of work. The unfortunate truth about work in war affected communities is that NGO intervention and support will be needed for a long time to come.

Direct Impact: 400; Indirect Impact: 2,800

Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- How will permagardening benefit women beyond easing hunger? Could it help heal emotional wounds?

- What are the long-term benefits, especially for the two-thirds who are children?

- How does this program fit in with the microfinance movement?

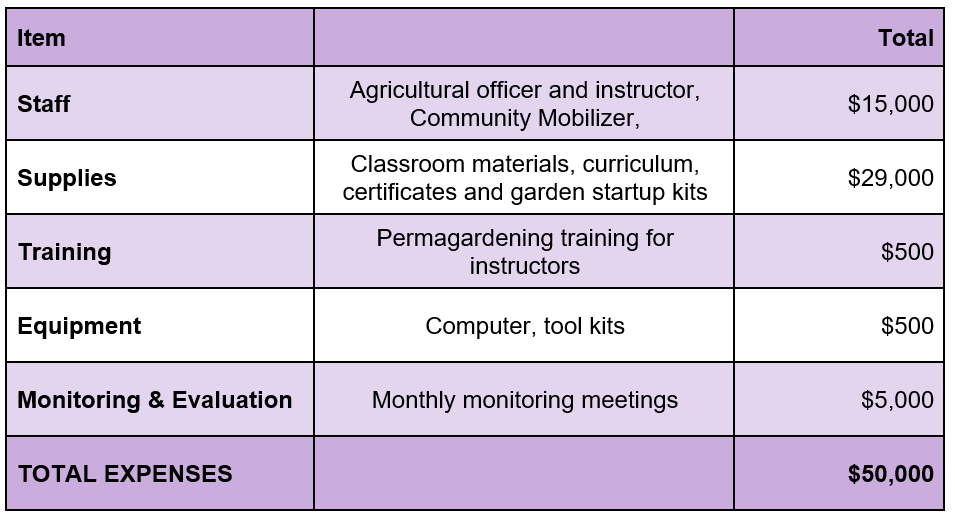

How the Grant Will be Used

Dining for Women’s grant of $50,000 covers program staff, supplies and equipment, training, and program monitoring expenses for 400 participants.

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love this project because it helps post conflict communities and refugees recover and rebuild their lives while learning valuable skills to ensure their food security, economic sustenance and good health.

Evidence of Success

AWR has improved the lives of over 5,000 women through its microfinance, literacy, and agriculture programs. The Permagarden Program has provided 2,000+ women increased access to food. Through the Organic Field Crop Program, over 800 women have gained ecological training. The majority of these participants have seen higher yields, better nutrition and increased income. Permagardens are now being implemented in Chad, Niger, and DRC, and the programs are based on AWR’s work and the years spent fine tuning the methodology.

In 2014, AWR was the recipient of the Leah Horowitz Humanitarian Award from the Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University.

Voices of the Girls

Success story:

Lilly has had her permagarden for one year. Her family of 12 – including five biological children and six orphans – used to go to sleep hungry. The year before she started her garden she had one bag of beans (75Kg) to feed everyone and pay for school fees. Now she and her family eat on a regular basis and all the children go to school. Lilly even started a second permagarden, and she plans to sell everything from this garden to be able to invest in goats and pigs.

“Inside South Sudan there is insecurity, food shortages and gross human rights abuses. This is what has prompted these people to flee to Uganda and safety.”

-UNHCR spokesperson Babar Baloch

“After seeing the soldiers had reached home my husband wanted to run. They caught him. After arresting him they didn’t even use a single bullet. They used knives and just stabbed him until he died… They took ropes and started tying my husband and took me inside. They tied his hands together behind his back. Even after they killed him, they kept stabbing his body with a bamboo stick… My husband also was a businessman with a shop and a bar… I think the soldiers knew he sold a cow and maybe they wanted the money… The soldiers beat me on the back and stepped on my stomach. One was holding me and brought me back to the compound and started kicking me. He told me he wants to get the money off my husband, if I don’t get the money they are going to kill my husband. I managed to escape through the window.”

-Joyce, a 37 year-old refugee from Kajo Keji in South Sudan. She arrived in Uganda in December 2016 with nine children, five of her own and four of her husband’s children by another wife. Her husband was killed, leaving her responsible for all the children. The oldest is 15 and the youngest is 11 months old. Joyce described the brutal killing of her husband to Amnesty International. He was stabbed to death in September 2016 by uniformed men whom she believes were government soldiers.

About the Organization

Linda and Thomas Cole established African Women Rising (formerly known as Community Action Fund for Women in Africa) in Santa Barbara, California, in 2006 after studying and working in Africa for more than a decade. AWR has evolved from providing mainly agricultural and microfinance programs to providing education programs for adults and girls. They have expanded their agricultural programs to include natural resource management through organic field crop and permagarden programs. AWR has grown from a two-person start-up to a 48-person team, plus 46 additional part-time literacy instructors. The initial program assisted 150 women. Today the organization serves 4,500 women and men every year. Geographically, AWR has expanded its reach from one sub-county in Gulu district to the sub-counties of Bardege, Paicho and Palaro as well as Lamwo and Amuru districts.

Linda and Thomas Cole established African Women Rising (formerly known as Community Action Fund for Women in Africa) in Santa Barbara, California, in 2006 after studying and working in Africa for more than a decade. AWR has evolved from providing mainly agricultural and microfinance programs to providing education programs for adults and girls. They have expanded their agricultural programs to include natural resource management through organic field crop and permagarden programs. AWR has grown from a two-person start-up to a 48-person team, plus 46 additional part-time literacy instructors. The initial program assisted 150 women. Today the organization serves 4,500 women and men every year. Geographically, AWR has expanded its reach from one sub-county in Gulu district to the sub-counties of Bardege, Paicho and Palaro as well as Lamwo and Amuru districts.

AWR develops programs based on evidence of need. For instance, its Functional Adult Literacy program was established after seeing that savings groups with high levels of illiteracy did not perform well. Because these individuals were unable to read or write, they had difficulty tracking their savings. AWR is passionate about improving the lives of women and girls who are marginalized and in poverty. As females traditionally run the household and care for the young and the elderly, AWR works to ensure that they have access to the resources necessary for survival. Not only do these women carry the heaviest burdens in conflict and post-conflict situations, they are also central to the daily work of repairing fractured communities.

AWR’s four program areas include adult education, girls’ education, agriculture, and microfinance.

Where They Work

Uganda is a landlocked country a little smaller than the state of Oregon but home to over 35 million people. Most live in the central and southern regions, particularly along the shores of Lake Victoria and Lake Albert. The population is young and among the fastest growing in the world, with the median age just 15 years old. Although the official language is English, there are over 30 indigenous languages spoken.

The Ugandan landscape is mostly plateaus surrounded by mountains. It contains substantial natural resources, including arable land where 80 percent of the workforce is employed. Uganda shares borders with five countries: The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and South Sudan. AWR works primarily in the Acholi region of northern Uganda. The region is recovering from a 22-year-long armed conflict between the Lord’s Resistance Army rebels, led by Joseph Kony, and the government of the republic of Uganda. The instability and influx of refugees in neighboring Sudan have had a serious effect on Uganda, as Sudan was Uganda’s primary export partner.

Uganda is one of the poorest countries in the world, with 38 percent of the population living on less than $1.25 per day. Poverty is especially pronounced in the rural areas, where women not only work in the agricultural sector, but also take care of their families. The average Ugandan woman spends nine hours a day on domestic tasks, including cooking, fetching water and firewood, and caring for children, the elderly, the sick, and orphans. Some women attempt to supplement their incomes by rearing animals, but finding the time is challenging. Gender inequality is fact of life in Uganda. Because of this, many women are unable to attain higher education, participate in community life, or break away from abusive husbands. Many Ugandans have emigrated to southern or western Africa looking for jobs, security, and an escape from poverty.

A closer look at climate change and food security

Climate change has had a negative effect on agriculture in developing countries, and if the tide does not turn, the future appears even more challenging. One study estimates that if trends continue, up to 20 percent more people will be at risk of hunger. More frequent and extreme weather events have already been seen, but there is much concern about a total change in temperature and rainfall patterns. Even slight changes can increase the risk of crop failure, new pests and diseases, loss of livestock, and access to seeds.

There are four dimensions of food security: availability, accessibility, utilization, and food system stability. According to scientists, all four will be affected by climate change. In addition, it will impact health and the ability to earn a living. Unfortunately, those who are already vulnerable, such as women and children, are the most likely to feel the brunt of climate change.

It is imperative that strategies be developed and deployed to mitigate the effects of climate change. What is needed is a shift from conventional farming toward more sustainable methods such as those found in AWR’s permagardens. This will assure a more resilient production system and better diversification of crops. Learning these techniques is especially important for refugees, who aim to someday bring what they have learned back to their countries.

Source Materials

http://www.fao.org/forestry/15538-079b31d45081fe9c3dbc6ff34de4807e4.pdf

http://unctad.org/en/Docs/osgdp20111_en.pdf

http://www.g20-insights.org/policy_briefs/achieving-food-security-face-climate-change/

http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/communications/wfp258981.pdf

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html

http://www.jlof.net/about-jlof/about-uganda-and-acholiland/