Mission

Mali Health’s mission is to reduce maternal and child mortality in resource-poor communities in West Africa. It improves access to quality primary care at low costs, while increasing the capacity of and participation in local health systems.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

Mali is a challenging place to be a woman and a mother. In this landlocked West African country, far too many women and children are lost to preventable death. One in eight children die before their fifth birthday and one in 26 women die in childbirth. Save the Children generates an annual State of the World’s Mothers Report that documents the condition of maternal health and well-being. Mali is consistently at the bottom of the list, ranked the fourth worst place to be a mother or a child under 5. The Gender Development Index, a measure which considers the Human Development Index from a women’s empowerment perspective, ranks Mali in the bottom 10: 179th of 188 for gender equality.

Life is particularly grueling in the slum communities of Bamako, the capital city, where residents lack employment or education beyond primary school. The women in these slums are among the poorest and least educated in Malian society, working almost exclusively in the informal sector with no guaranteed income. Malian society is traditionally patriarchal and rigidly hierarchical, and women often lack a great deal of decision-making power even in their own homes. Many of the women are young: 22 percent are under age 25 and 75 percent are under age 35. They have extremely limited education, with 60 percent having no formal schooling and an additional 28 percent having only a primary school education.

Life is particularly grueling in the slum communities of Bamako, the capital city, where residents lack employment or education beyond primary school. The women in these slums are among the poorest and least educated in Malian society, working almost exclusively in the informal sector with no guaranteed income. Malian society is traditionally patriarchal and rigidly hierarchical, and women often lack a great deal of decision-making power even in their own homes. Many of the women are young: 22 percent are under age 25 and 75 percent are under age 35. They have extremely limited education, with 60 percent having no formal schooling and an additional 28 percent having only a primary school education.

Access to healthcare is extremely limited. Only 55 percent of Malian women give birth in clinics; for the poorest women that number falls to 25 percent. Only 41 percent attend four WHO-recommended prenatal visits and 25 percent receive no prenatal care. This is due in large part to the decentralized Malian health system that leaves each community clinic faced with the challenge of raising revenue through a fee-for-service system. This places the burden of payment on poor families. These communities lack the training, financial resources, and education to manage clinics effectively, so both people and clinics struggle. Women have little power to pay for healthcare or anything else because of their traditional exclusion from financial management in their families. As a result – and despite high levels of preventable diseases like malaria, diarrhea and malnutrition – clinic utilization in these communities is low, leaving clinics under-resourced, under-staffed, and thus unable to provide the high quality of health care that community members deserve and need.

The Project

Mali Health’s Health Savings program was created to meet the needs of the Bamako slum community, whose residents overwhelmingly desire a means by which to save and pay for healthcare. The program provides access to credit to Bamako’s poorest women, which allows them to pay for their healthcare expenses and ultimately enhances their social standing. MH’s Health Savings program was piloted in 2013 with 100 women in two communities. Today it serves seven communities and 3,335 women around Bamako. With Dining for Women’s grant, the program will expand into two new sites, Sebenicoro and Sabalibougou, thus directly benefiting 5,000 women and, factoring in their families, indirectly benefit 20,000.

MH’s Health Savings program is based on the traditional West African tontine model in which women pool small amounts of money that is disbursed to members on a rotating basis. Groups of 20 – 25 women meet weekly to deposit savings into two shared accounts: one for health-related expenses and the second to support income-generating activities. By taking turns pooling and sharing money, the program ensures that participating women have uninterrupted, speedy access to funds.

MH’s Health Savings program is based on the traditional West African tontine model in which women pool small amounts of money that is disbursed to members on a rotating basis. Groups of 20 – 25 women meet weekly to deposit savings into two shared accounts: one for health-related expenses and the second to support income-generating activities. By taking turns pooling and sharing money, the program ensures that participating women have uninterrupted, speedy access to funds.

Members leverage the pooled funds in the form of small, easy-to-access loans. Health loans carry no interest and are used to finance the cost of clinic consultations and medications for group members and their children. General loans do carry interest and are used by group members to pursue activities that will help to raise their income, such as purchasing wholesale goods to sell at the local market or learning a skill that can be translated into a profitable trade. These women also have increased access to funds for income-generating activities, and gain basic financial knowledge and the ability to plan for small business expenses. As women take advantage of these opportunities to build financial independence, they acquire influence and decision-making power in their families and in the community.

The groups’ weekly deposit amounts are decided upon by the women themselves, in addition to other rules that define repayment schedules and late fees. Borrowers repay their loans over an agreed upon timeline. Interest earned is also deposited in the shared fund and distributed back to the members along with the accumulated savings at the end of the loan cycle. On average, loan cycles last about nine months.

Organized into these neighborhood savings groups, women build social solidarity and increase their self-efficacy as they participate in financial training and begin managing their own finances. The familiarity of this practice, and the fact that most savings groups are comprised entirely of women who already know one another, has already led to the program’s tremendous popularity. In fact, the driving force behind the program’s explosive growth has been the group members themselves, who share their enthusiasm with friends and neighbors, encouraging them either to join existing groups or to form their own.

Organized into these neighborhood savings groups, women build social solidarity and increase their self-efficacy as they participate in financial training and begin managing their own finances. The familiarity of this practice, and the fact that most savings groups are comprised entirely of women who already know one another, has already led to the program’s tremendous popularity. In fact, the driving force behind the program’s explosive growth has been the group members themselves, who share their enthusiasm with friends and neighbors, encouraging them either to join existing groups or to form their own.

In addition to the groups, MH facilitators help participants access care more quickly by facilitating links with local clinics and providing preventive health education on reproductive health, prenatal care and childhood nutrition and illnesses. Further, the women make commitments to the group at the start of each cycle, promising to purchase specific preventive health products such as mosquito nets, soap and chlorine tablets. The women also learn health-promoting behaviors, thereby utilizing social support for follow through. Participants are encouraged to seek care within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms, thus increasing the timeless of care. In addition, Mali Health animateurs (facilitators) lead group talks at each meeting on relevant health topics, such as malaria prevention, prenatal care and other topics of members’ choosing.

Prospective participants are identified and selected by MH community health workers, who provide the link between their communities and the health system. These women and their children benefit immediately from improved access to health services, preventing or lessening the severity of illness and increasing chances of maintaining health. As women have access to capital and social solidarity to support one another, their economic activity increases. As their incomes rise and they are able to contribute more to their families’ well-being, their influence and decision-making power in the home and in the community grows as well, allowing them to leverage their power to fulfill their own and their families’ needs.

Prospective participants are identified and selected by MH community health workers, who provide the link between their communities and the health system. These women and their children benefit immediately from improved access to health services, preventing or lessening the severity of illness and increasing chances of maintaining health. As women have access to capital and social solidarity to support one another, their economic activity increases. As their incomes rise and they are able to contribute more to their families’ well-being, their influence and decision-making power in the home and in the community grows as well, allowing them to leverage their power to fulfill their own and their families’ needs.

Health Savings is designed to keep external financial investment to a minimum. Mali Health does not contribute funds to the communal coffers maintained by savings groups, and though Mali Health staff attend group meetings, the groups operate autonomously. Further, the ability to save for health care expenses is a skill and habit that will not require long-term involvement by Mali Health, once introduced.

Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- Why might participants’ husbands encourage their wives to participate in the Health Savings program?

- How does the social aspect of the tontines benefit the members?

- How could the Health Savings program affect the quality of care provided through clinics and other providers?

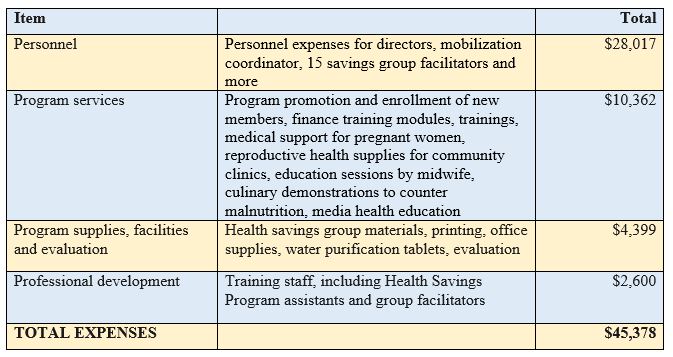

How the Grant Will be Used

Dining for Women’s one-year, $45,378 grant will allow Mali Health to provide the education, training and related program expenses to provide the Health Savings program to two new communities.

Direct Impact: 5,000; Indirect Impact: 20,000

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love this project because it simultaneously enhances women’s health, economic standing and social status.

Evidence of Success

Since 2014, Mali Health’s primary program of free healthcare for families has eliminated the death of expecting mothers and children under 5 in the eight service areas.

In 2014, Mali Health played a leading role in the response to and containment of the Ebola outbreak in Bamako, working closely with the World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and the Malian government to train clinics and community members on how to identify and monitor for signs of illness and how to prevent the spread of the virus. At the end of 2014, Mali Health was recognized by the World Health Organization for their leading role in tracing and containing the Ebola outbreak in Mali. From 2012-2015, they worked with researchers from Brown University and Innovations for Poverty Action to conduct a randomized control trial of the Action for Health program to assess the impact of Community Health Worker services and free care on health outcomes among enrolled mothers and children.

In 2014, Mali Health played a leading role in the response to and containment of the Ebola outbreak in Bamako, working closely with the World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and the Malian government to train clinics and community members on how to identify and monitor for signs of illness and how to prevent the spread of the virus. At the end of 2014, Mali Health was recognized by the World Health Organization for their leading role in tracing and containing the Ebola outbreak in Mali. From 2012-2015, they worked with researchers from Brown University and Innovations for Poverty Action to conduct a randomized control trial of the Action for Health program to assess the impact of Community Health Worker services and free care on health outcomes among enrolled mothers and children.

Total Health Savings program enrollment nearly doubled in 2015 and the amounts saved for health expenses and income-generating activities both more than doubled. In addition, every pregnant woman in Mali Health’s savings groups gave birth in a health facility in 2015 through Mali Health’s new program, Saving for Health and Reproductive Empowerment (SHARE). Women in Health Savings who become pregnant are given the option to enroll in SHARE groups in which they save additional weekly sums in a personal cash box. By saving money specifically for her pregnancy, each woman can finance her own prenatal care and clinic-based delivery, giving her and her child the best chance of starting a healthy life together. As all SHARE group members are expecting mothers, they are also able to offer one another social support and share knowledge. Once a month, Mali Health organizes workshops in which doctors, nurses, and midwives attend SHARE group meetings and teach the women about numerous topics, including proper nutrition, how to recognize danger signs while pregnant, and the importance of prenatal care, postnatal care and childhood vaccinations.

In 2015, MH also exceeded their goal of ensuring all participating women and children accessed care within 72 hours of first symptoms. They did so in 48 hours on average. Women were more easily able to access funding for health expenses as well. While only 3.9 percent were able to access a health loan from a formal microfinance institution, 44.9 percent of women in the savings groups were able to access a health loan whenever needed. The impact on women’s sense of empowerment and self-efficacy was one of the strongest results of the program in 2015, with 98.4 percent of women surveyed reporting that being in a Health Savings group increased their financial autonomy and capacity to manage their own finances.

In 2015, MH also exceeded their goal of ensuring all participating women and children accessed care within 72 hours of first symptoms. They did so in 48 hours on average. Women were more easily able to access funding for health expenses as well. While only 3.9 percent were able to access a health loan from a formal microfinance institution, 44.9 percent of women in the savings groups were able to access a health loan whenever needed. The impact on women’s sense of empowerment and self-efficacy was one of the strongest results of the program in 2015, with 98.4 percent of women surveyed reporting that being in a Health Savings group increased their financial autonomy and capacity to manage their own finances.

One of MH’s founders, Caitlin Cohen, won the Do Something award for Mali Health’s early work. With the Malian government, MH has been recognized for work in mobile health efforts. In 2014, Mali Health was listed in the Sustainia100, a network of sustainable solutions to international health challenges, and they were named a recipient of the Grand Challenges Explorations grant for innovative use of quality improvement tools in small Malian clinics.

Voices of the Girls

“I am very grateful to everyone in the group for your generosity. [Health Savings] is very important to the women of this community. With initiatives like this, we will not be afraid to reach out for care for a lack of money because with the health fund, there is hope.”

“I am very grateful to everyone in the group for your generosity. [Health Savings] is very important to the women of this community. With initiatives like this, we will not be afraid to reach out for care for a lack of money because with the health fund, there is hope.”

Assan, Health Savings group member

“After spending a long and restless night with my son, I quickly took a loan of 10,000 CFA (approx. $16-17) to bring him to the health center. This amount, though small, could be enough to save [my son] from malaria. We live in a suburban settlement area where the houses are surrounded by crops – something that increases the possibility of contracting malaria during the winter. A big thank you to the health fund and the members of my group for this gesture of solidarity.”

Keita Djenebou Camara, Health Savings group member

“Outside of better financial access, this program has really helped pregnant women. The program provides reimbursements for the costs of our prenatal consultations during our pregnancy, which motivates us to frequently visit the health centers. We joined this program not too long ago, but the impact is already perceptible in our group. Outside of our group activities, we have initiated a solidarity tradition to further strengthen our bonds. Each time a mother gives birth, we collect a piece of soap from each member of the group so that the new mother can wash her newborn. We sincerely thank Mali Health. [The old proverb applies:] they’ve taught us to fish, rather than giving us fish. This initiative truly puts women first. We invite all women to join us to take care of ourselves and our children with the support of Mali Health.”

Awa Keïta, Health Savings group member

About the Organization

Founded in 2006 by a Malian midwife and three Brown University undergraduate women, Mali Health began in Sikoro, a slum community in Bamako, Mali. This team of women supported Sikoro residents in prioritizing local health needs and in collectively designing innovative ways to address them. Residents identified many challenges and were especially impassioned by the links between women’s empowerment and maternal and child survival – this became the foundation of Mali Health. Mali Health believes that mobilizing community members to advocate for improved health services is critical to achieving systemic change and they use the knowledge and assets that exist in communities to help generate that change.

Mali Health uses an integrated approach to overcome the barriers to healthcare faced by the poorest women and children in Bamako. They train community health workers (CHWs) to regularly engage families in their communities, empowering them with preventative health education and bringing the health system to the doorsteps of the most vulnerable. In addition to CHW services, Mali Health provides free care to pregnant women and children under three years old.

Mali Health uses an integrated approach to overcome the barriers to healthcare faced by the poorest women and children in Bamako. They train community health workers (CHWs) to regularly engage families in their communities, empowering them with preventative health education and bringing the health system to the doorsteps of the most vulnerable. In addition to CHW services, Mali Health provides free care to pregnant women and children under three years old.

In recent years, Mali Health has extended its reach beyond the community level and has begun targeted health system strengthening efforts, designed to improve the quality of care at the clinics.

Mali Health has partnered with a number of community groups and government partners, including many women’s groups, in the design, implementation and evaluation of their programs. To develop Health Savings, Mali Health worked with Oxfam to adapt their Savings for Change program, expanding the focus beyond women’s economic empowerment to include an emphasis on health education and improving access to health care. Mali Health also collaborates with Freedom from Hunger, an organization that offers expertise in financial training.

Where They Work

Mali Health serves mothers and children in eight peri-urban slums of Bamako, with a population of approximately 140,000. These communities are characterized by high levels of poverty, low education and significant geographic and financial barriers to public services, particularly the health system.

Bamako has been inhabited for more than 150,000 years as part of the West African empires, a French colony until 1960. It is Mali’s capital and largest city, with a population that has experienced pronounced growth to 1.8 million. The uncontrolled growth has caused problems with traffic, sanitation and pollution. Today, the city exhibits extreme poverty.

Mali is characterized by a tropical savanna climate. Situated between the Sahara and the Gulf of Guinea, it is extremely hot all year. Virtually no rain falls between November and April, and very little falls during the rest of the year. Bamako spans both sides of the Niger River. Most roads are unpaved, which leads to dust in the dry season and mud in the rainy season.

A closer look at health emergencies in developing countries

A trip to the emergency room may feel unfamiliar and unsettling in the US, but in developing countries it might be fatal. Many hospitals, clinics and associated medical facilities lack the equipment, medication and staff to accommodate even basic maladies. Many emergencies start small but become serious because they go untreated. An infection may go unchecked because the patient can’t reach a hospital or pay for services, while infected tissue or organs become increasingly inflamed. Unsanitary conditions may lead to diarrhea and result in dangerous levels of dehydration. According to the World Health Organization, even during life-threatening emergencies, timely treatment is not always a priority for health systems in developing countries. In addition, a lack of on-the-job safety measures puts workers at risk for emergencies.

One out of ten deaths in low-income countries is due to lower respiratory infections – more than double the incidence in high income regions. Developing nations fight malaria, tuberculosis, diarrheal diseases and perinatal conditions – all conditions that either do not exist or are easily treated where healthcare is accessible and adequate. In addition, due to inadequate infrastructure, unpaved roads and a lack of road rules, road traffic accidents are all too common in developing nations, causing almost 2 percent of all deaths.

Source Materials

http://www.who.int/bulletin/archives/en/80(11)900.pdf

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310.pdf