Mission

ConTextos transforms the education experience so that students go beyond rote learning to develop literacy and socio-emotional skills like critical thinking, analysis, and creativity.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

El Salvador is dubbed the homicide capital of the world and the deadliest country in Latin America for women and girls. This violence reflects generations of trauma from war and gangs and the ripple effect endured by generations to follow. The traumatic experiences impair children’s cognitive and emotional development. Children who have been victims of violence are more likely to engage in crime and antisocial behavior, developing beliefs that violence is an appropriate means of settling conflict. This mindset played out in homes and on the street as a survival mechanism in El Salvador’s war zones.

Women take the brunt of the brutality, enduring sexual, physical, and psychological violence. Salvadoran women suffer violence in the street and in their homes and often end up in prison because of crimes committed by their husbands and boyfriends. Sadly, there is a social indifference and acceptance of this phenomenon. In fact, it is so prevalent that it is considered normal, even by women. Women in prison are some of the most marginalized and traumatized. These women, some of whom are guilty of crimes that were motivated by basic needs to care for their children, give birth to and raise their children behind bars. In the Granja Penitenciaria de Mujeres de Izalco (Prison Farm for Women in Izalco, GPMI), children spend their first crucial years of life with women with unhealed trauma.

In the GPMI, each day these children are sent to the Child Development Center (CDC). There, they are cared for by 35 Childcare Volunteers. These female inmates are responsible for the physical well-being of these children but have no training in early stimulation, cognitive development, or how to provide support for the women who do not access the CDC. Eighty percent of inmates in El Salvador have received less than a ninth-grade education, while 7.2 percent have no schooling at all. They rely on the parenting they remember from how they were raised or have observed in others, the same parenting that is failing Salvadoran youth who now turn to gangs or emigration to flee the violence.

In the GPMI, each day these children are sent to the Child Development Center (CDC). There, they are cared for by 35 Childcare Volunteers. These female inmates are responsible for the physical well-being of these children but have no training in early stimulation, cognitive development, or how to provide support for the women who do not access the CDC. Eighty percent of inmates in El Salvador have received less than a ninth-grade education, while 7.2 percent have no schooling at all. They rely on the parenting they remember from how they were raised or have observed in others, the same parenting that is failing Salvadoran youth who now turn to gangs or emigration to flee the violence.

Not surprisingly, El Salvador is one of the worst countries to be a girl. Statutory rape is widespread, 70 percent of victims of sexual violence are girls under age 20, and child marriage was only made illegal in 2017. Emblematic of the everyday sexual, psychological, physical, and economic violence is the rate of femicides. El Salvador has the highest rate of femicides in Latin America, at 8.9 homicides per 100,000 women. In October 2017, a man killed his girlfriend in front of their two children as she attempted to press charges against him for domestic violence.

There are many reasons why this unfortunate environment persists for Salvadorian women and girls, starting with the fact that inside and outside of prison, children are born and raised in a violent machista society without the proper social supports. There are no public structures or support to effectively educate and provide integral healing. While schools could be a positive influence, children receive an education based on rote memorization in classrooms and communities that tend toward male dominance. Young mothers receive no parenting classes to confront cycles of violence and neglect or develop stimulating, supportive homes.

Only 20 percent of schools claim to have adequate reading materials and space. Reading at school is infrequent and almost non-existent in the average home, especially as a shared experience between parent and child. If you ask why there is so much violence in this small country, many people will tell you, “That’s just the way it is.”

The Project

This project, Soy Autora: Women Author the Future, aims to develop literacy-rich environments for incarcerated women and children as a tool for healing and development and to work intensely with moms to capture their stories to share publicly. It transforms the educational experience of both women and children, promotes healing and positive social-emotional skills, and teaches these women how to pass along these skills to their children. This is an opportunity to inspire women’s creativity and healing by writing their own stories and to provide the groundwork for reading for pleasure in the small children they care for.

The program assists women and their children at the GPMI prison in Izalco, Sonsonate, El Salvador. There, training is provided to incarcerated Childcare Volunteers, who develop a library, implement strategies that stimulate learning, literacy and dialogue, and participate in the Soy Autor (“I am an author”) writing program to publish their memoirs. The one-year program will directly benefit 35 Childcare Volunteers and 184 children, and indirectly touch the lives of 418 other women detained at GPMI. After these women are released, the expectation is that the benefits will be felt by family members and the community at large.

The outcomes will include a functioning library space – which neither mother nor child has ever experienced – that encourages and models best practices in learning and early stimulation for literacy. Mothers will gain self-esteem and have better relationships with the children they are raising behind bars, and incarceration will be an opportunity for healing and rehabilitation, not just punitive punishment. There will be demonstrable increases in interest in reading, improved reading and writing scores, and improved measures on social emotional skills. Best of all, by telling their stories and strengthening their emotional health, these women will have the chance to change their lives and the lives of the small children in their care. They will leave prison one day and need more than just vocational skills to move on: they need the emotional resilience to break the cycle of violence in their communities and families.

The outcomes will include a functioning library space – which neither mother nor child has ever experienced – that encourages and models best practices in learning and early stimulation for literacy. Mothers will gain self-esteem and have better relationships with the children they are raising behind bars, and incarceration will be an opportunity for healing and rehabilitation, not just punitive punishment. There will be demonstrable increases in interest in reading, improved reading and writing scores, and improved measures on social emotional skills. Best of all, by telling their stories and strengthening their emotional health, these women will have the chance to change their lives and the lives of the small children in their care. They will leave prison one day and need more than just vocational skills to move on: they need the emotional resilience to break the cycle of violence in their communities and families.

To achieve these outcomes, ConTextos employs a three-pronged approach:

- Train Literacy Leaders – ConTextos trains all 35 Childcare Volunteers to become Literacy Leaders. This group ensures the greatest impact within the prison, as they have contact with both children and mothers. Through regular trainings and coaching, Leaders develop skills to cultivate a love of literacy in the children they care for and share the joy of reading and writing with their incarcerated peers, including emergent learning and childhood development strategies and theory.

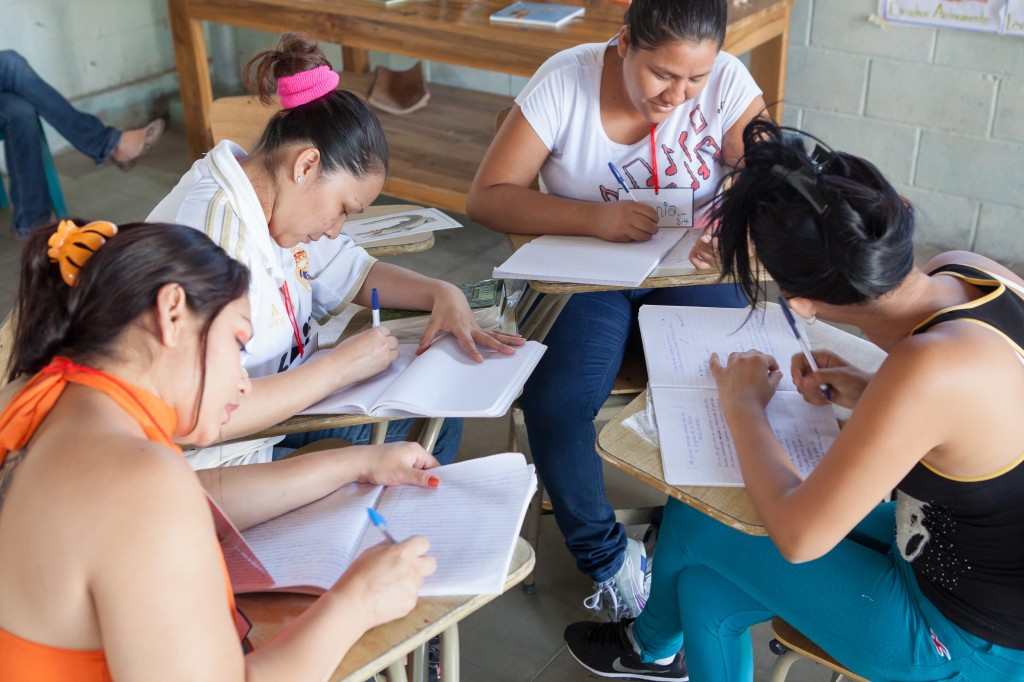

- Initiate the Soy Autor (“I am an author”) and Soy Lector (“I am a reader”) Writing Workshops – During Soy Autor, participants reflect on pivotal life events, using mentor texts to “read as writers” as they follow the writing process to draft, revise, edit, illustrate, and publish memoirs. Incorporating works written by other at-risk and incarcerated youth from previous Soy Autor programs connects women to a bigger effort to create positive, peaceful projections for El Salvador. Women participate in facilitated dialogue to foster social emotional learning and conflict resolution, make meaning of their realities and project for the future, and build positive self-expression and behavioral skills like empathy and tolerance.

Their beautiful, illustrated memoirs will be shared throughout El Salvador and the region in public schools and NGOs to curtail the cycle of social exclusion and hopelessness that permeates El Salvador.

Their beautiful, illustrated memoirs will be shared throughout El Salvador and the region in public schools and NGOs to curtail the cycle of social exclusion and hopelessness that permeates El Salvador.

Owning one’s own story is essential to become an empathic leader of one’s own life and of others. Telling one’s story requires a great deal of decision-making. ConTextos asks each author, “Who is your audience? How do you want them to read you? What message do you want to communicate? What symbols would help you tell your story? How do you want your readers to feel?” Authors don’t know the answers right away, but as they build their stories in community they grow in confidence and explore the answers. These questions are about more than just their stories: they are about identity, self-projection, and taking control over their lives. - Develop and maintain a library – ConTextos will create a new children’s library in the CDC, with book lending and regular visitation schedules. ConTextos will curate and purchase a collection of 500 new books. Libraries will be run and maintained by Literacy Leaders and serve as a safe space for ongoing literacy activities even after this grant. The GPMI library will be modeled on ConTextos’ other libraries: safe, beautiful, engaging, welcoming, stimulating.

The incarcerated women will design their library. They will create and maintain an attractive, functional library for children and inmates, painting, arranging shelves and seating, and modeling community-engaging routines. They will learn the power of regularly reading with children and in community to spark peaceful engagement and high expectations. Through workshops and modeling, the project will foster read-alouds, bedtime stories, book clubs, and sisterhood. And it will demonstrate the potential to reimagine incarceration as a time for rehabilitation and healing rather than just punishment.

Major partners for this work include the Ministry of Education (MINED), Plan International, and General Direction of Prisons (DGCP) which will ensure powerful programmatic implementation that transforms the lives of participants and creates lasting, sustainable change for the GPMI institution with potential for replication at other sites.

Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- How do you think reading and writing will be therapeutic to the beneficiaries of this project?

- What societal changes might occur after the public is made aware of the prisoners’ stories?

- Once released, how might these women take what they have learned into their communities?

How the Grant Will be Used

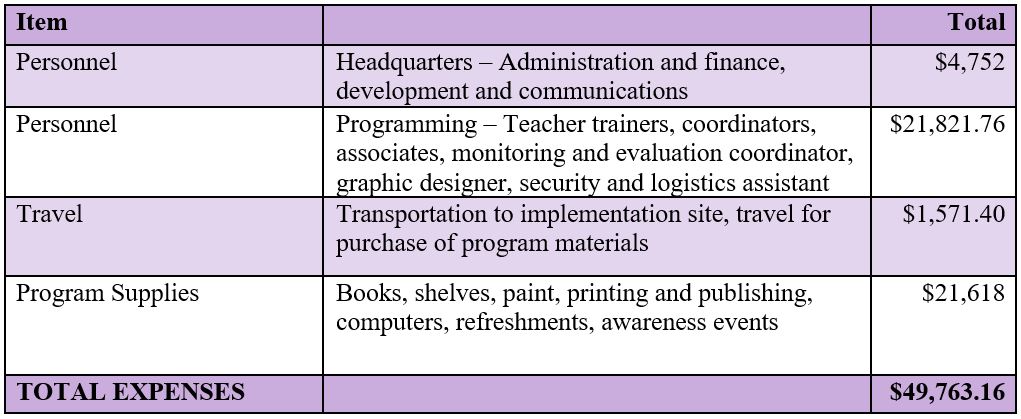

Dining for Women’s grant of $49,763.16 for one year will support personnel and employee benefits for employees, including those conducting Literacy Leader trainings and Soy Autor workshops, travel to the center, and program supplies. It will directly impact 35 young women and 184 children ages birth – 5 years, and it will indirectly impact 418 women.

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love ConTextos’s focus on restorative justice in their work with incarcerated women and their children. In a country where violence is endemic, these women participate in facilitated dialogue and creative writing workshops to foster social emotional learning and conflict resolution. These skills help build positive self-expression and behavioral skills like empathy and tolerance. It promotes healing and success in learning, work, and relationships in their future lives outside the prison.

Evidence of Success

Soy Autor has proven to be a powerful process for young people to transform the way they interact with their families and peers. One author from a juvenile detention center wrote, “Despite the fact that I made mistakes and I was disobedient, as time passed I reflected and made progress to see my family in a different way. Now I don’t see my mother’s advice as annoying, hard, like rain that falls on the roof. I’ve learned to see that it is wise.”

Students read and write within a rehabilitative environment. In 2017, they improved dialogue skills by 82 percent, teamwork by 93 percent, and use of social emotional language by 61 percent. All these skills are essential to process their past, and to heal and change as they prepare for their release. Empathy skills grew 84 percent over the course of just three months of classes. Respect for others, essential to a peaceful society, also grew 58 percent. Positive feedback in pairs grew 100 percent by the end of classes. Soy Autor sessions are a safe space where authors realize that being vulnerable doesn’t mean being weak. Reading, sharing and writing about their experiences shows bravery and resilience.

Students read and write within a rehabilitative environment. In 2017, they improved dialogue skills by 82 percent, teamwork by 93 percent, and use of social emotional language by 61 percent. All these skills are essential to process their past, and to heal and change as they prepare for their release. Empathy skills grew 84 percent over the course of just three months of classes. Respect for others, essential to a peaceful society, also grew 58 percent. Positive feedback in pairs grew 100 percent by the end of classes. Soy Autor sessions are a safe space where authors realize that being vulnerable doesn’t mean being weak. Reading, sharing and writing about their experiences shows bravery and resilience.

Dr. Jim Garbarino, professor and author specializing in issues of trauma, violence, and children, who has worked with ConTextos for four years, says: “From my more than 30 years of work with inmates, I have learned writing about their lives and entering into a dialogue about what they write is one of the most important ways available to help them process that trauma, and thus begin the process of healing that can lead eventually to pro-social behavior.”

The work goes beyond those prison walls. The published Soy Autor memoirs also develop empathy and awareness among the general population, including the 1,500 teachers in the ConTextos network who in turn work with nearly 50,000 students, funders and partners, thought-leaders and policy makers. The work shows that change is possible, and it helps elevate the stories of Latin America’s most vulnerable women.

Finally, the books and stories help change hearts and minds within greater society. ConTextos has repeatedly seen the impact that published books have upon readers, including teachers and their students and other institutional partners. Published Soy Autor books turn statistics into real stories and help spark public outcry and political will. Stories improve teachers’ engagement with their students and families, develop empathy among hardline “iron-fist” law enforcement, and pique the interest of donors. The power of these stories builds the relationships and funding sources that helps the program to grow and expand.

From 2011-2017, ConTextos served:

- 484 youth at-risk of gang violence and recruitment, 15-18 years old

- 172 youth in conflict with the law, 14-18 years old

- 18 girls and teenage mothers and 154 boys

- 38 adults in conflict with the law: 12 women and mothers raising their children in prison and 26 men

- 47,346 students aged 4-18 in 80 public schools: 22,994 girls, 24,352 boys and 1,236 K-12 teachers

In 2017, ConTextos achieved systemic influence within the ISNA juvenile detention system, working with staff not only to implement programming, but providing the first system-wide training for staff around asset-based and trauma-informed learning environments to change the belief-systems around incarcerated youth and their families. Also in 2017, ConTextos trained Orphan Helpers’ permanent staff at juvenile detention centers to facilitate book lending and reading clubs, renovate library spaces with youth, and support general reinsertion efforts for post-incarceration. ConTextos has the support of the United Nations Development Programme, the US government’s International Narcotics and Law Enforcement and the InterAmerican Development Bank.

Voices of the Girls

Author Doris wrote about the violence she experienced growing up. When strangers came to her mother’s salon and commented on her looks, her mother replied, “You like her? Take her!” Doris remembers how she felt at just 6 years old, when they took her away: “My heart shrunk to the size of a mustard seed. Fear and anguish took over.” At 9 years old, she lived on the street and had already experienced everyday abuse. At 11, she smoked, used makeup, and later had her first boyfriend: “He kissed me and touched my skinny body—that scared me and made my stomach hurt. But my friends did it, they let boys touch them, and the boys fell in love with them.” At 13, she had found a “family” with a gang and was shot for the first time. Despite all of this, she never lost her longing for her mother. When she became a mother herself, she was overcome with the fear that she, like her own mother, might become a “dream thief.”

Author Doris wrote about the violence she experienced growing up. When strangers came to her mother’s salon and commented on her looks, her mother replied, “You like her? Take her!” Doris remembers how she felt at just 6 years old, when they took her away: “My heart shrunk to the size of a mustard seed. Fear and anguish took over.” At 9 years old, she lived on the street and had already experienced everyday abuse. At 11, she smoked, used makeup, and later had her first boyfriend: “He kissed me and touched my skinny body—that scared me and made my stomach hurt. But my friends did it, they let boys touch them, and the boys fell in love with them.” At 13, she had found a “family” with a gang and was shot for the first time. Despite all of this, she never lost her longing for her mother. When she became a mother herself, she was overcome with the fear that she, like her own mother, might become a “dream thief.”

The following quotes come from “I am” poems that women wrote about their hopes, fears, gifts, and dreams. Writing like this is a regular part of ConTextos workshops to give women the space to reflect, write, share and appreciate their unique identities.

“My gift to the world is my happiness, my peace. My greatest fear would be that my son forgot me. I wish I could see my own mother again.”

- Yesenia

“I’m afraid of the dark and of ghosts. I wish I could see my children and my grandma. Even so, I am a joyful person and I love to read!”

- Jackeline

“I feel happy when I achieve my goals. My gift to the world is my hope because it feels good to hope. I have hope that I’ll see my children and my mother again.”

- Esther

“I like having sisters, cake and life in general! My gift to the world is my experience and how easily I offer forgiveness. The life I’ve chosen and being a mother scare me.”

- Doris

“My gift to the world is my talent for smiling despite adversity. Small, closed spaces scare me. I would like to see my children with a good education and living their lives.”

- Roxana

“I am a sister of loneliness. I feel desperate and want to just take off running! My gift to the world are my moments of happiness and peace, but I’m afraid I won’t get to live moments like that ever again.”

- Xenia

About the Organization

ConTextos was founded in 2010 by Debra Gittler and Zoila Recinos, with a goal of reimagining incarceration as an opportunity for reflection and rehabilitation and recognizing the unique demands and opportunities for women raising their children in prison. Programming initially focused on teacher training in literacy best practices in public schools paired with the creation of active, attractive libraries. Soy Lector (“I’m a Reader”) transformed classes based on rote memorization and copying into spaces where students read challenging texts and shared their ideas through dialogue and writing. In 2013 ConTextos saw the need to create a powerful writing curriculum to address the haunting stories that students, now avid readers, were beginning to write about the reality of growing up in El Salvador. That lead to the development of Soy Autor (“I’m an Author”), a unique and innovative trauma-informed writing program to promote healing and empathy for the country’s most underserved populations.

The ConTextos three-year intensive teacher training program trains K-9 teachers in literacy best-practices including reading and writing workshops and creating safe-spaces for reflection and pro-social behaviors, including the development and management of school and community libraries. Teachers learn to use text as a basis to facilitate conversation that lifts the level of thinking, gets students engaged and sharing their ideas. Before ConTextos, each student’s notebook is identical because learning is based on rote copy. After ConTextos, students use books every day, check-out books once a week, and engage regularly in read-alouds and dialogue that serve as a transition toward written expression. By the end of the three years, teachers transform their literacy practice and create an attractive library of over 500 books and 30 Kindles with 250 e-books.

The Soy Autor Social Emotional Learning Curriculum targets young people affected by violence and trauma as victims, witnesses, or perpetrators, particularly in areas affected by gangs and poverty. Participants “read as writers” as they draft, revise, illustrate, and publish their memoirs. They learn to take and accept critical feedback, improve reading and writing skills, and reflect upon the past to imagine a different future. The Authors Circle demands accountability while embracing empathy, working in teams and independently to build prosocial behaviors that are the foundation for success in education, the workplace, and relationships. The published books are used to train teachers and thought-leaders to develop empathy, policy, and solutions based on real-life experiences of violence and trauma.

Where They Work

The smallest and most densely populated country in Central America at 6.1 million, El Salvador borders the North Pacific Ocean between Guatemala and Honduras. It is mostly mountainous with a narrow coastal belt and central plateau. This country is susceptible to volcanic activity, earthquakes, and hurricanes.

Population growth in El Salvador has declined in the recent past from an average of six children per woman in the 1970s to replacement level today, thanks to an increased use of family planning. The sterilization rate in women is among the highest in Latin America, and the use of injectable contraceptives is also growing.

Salvadorans fled to the US, Canada, and neighboring countries during the civil war between 1979 and 1992. Today, 20 percent of El Salvador’s population lives abroad, and the money sent back home accounts for close to 18 percent of GDP and is the second largest source of external income after exports. Funds sent from family members helps reduce poverty, which affects 35 percent of Salvadorans. El Salvador has one of the world’s highest homicide rates and pervasive criminal gangs.

ConTextos works in Izalco, Sonsonate, in the northwest corner of El Salvador. The organization serves 80 schools, all six juvenile detention centers, and three adult prisons in El Salvador. ConTextos has trained organizations in Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua to use their model. In 2017, ConTextos launched Soy Autor in Chicago, working with 18-24-year-olds at Cook County Jail and in marginalized communities.

A closer look at the power of writing to change a life

Writing is powerful medicine – for the mind as well as the body. Numerous studies validate the effectiveness of writing to mitigate anxiety, tragedy, and a host of other painful life experiences. It has even been shown to provide relief to people coping with cancer, heart disease, chronic pain, and AIDS. Those who write about what is bothering them tend to feel happier and sleep better. Researchers are beginning to study and understand why writing even benefits the immune system in some people.

Therapists often suggest that patients write to help heal from stresses and traumas. Regardless of the severity of the underlying issue, writing helps make sense of things. When our minds spin with worry or sink with sadness, putting words on paper feels cathartic. Writing may even help us find the right words that allow us to let go of concerns and maybe even find answers. Words on a page are safe when the only audience is oneself. Since the page doesn’t talk back, we can unleash our true feelings without fear of criticism. Journaling allows us to pour out our thoughts and feelings and release our negative emotions.

For some adults and children, turning fears or concerns into a work of fiction may help alleviate the underlying issue. For instance, a child may write about a violent or traumatic incident but change the ending. This helps the child feel a sense of control over the situation, if only on paper. Such is the case for the Salvadoran children served by ConTextos, whose lives may start off in the most challenging of conditions, but whose outlooks and prospects may be brightened when immersed in the beauty and power of the written word.

Source Materials

http://theweek.com/articles/638610/how-use-writing-overcome-anxiety-tragedy-heartache

http://www.indypl.org/readytoread/?p=1086

http://www.apa.org/monitor/jun02/writing.aspx

https://writingcooperative.com/writing-to-cope-when-nothing-else-seems-to-work-511a3fc8f696

https://www.writingcity.com/act-of-kindness-campaign-writing-prompts-to-help-students-deal-with-tragedy.html

https://thewritepractice.com/heal/