Mission

Development in Gardening enables vulnerable and HIV-affected communities to meet their own needs and improve their well-being through nutrition-sensitive and sustainable agriculture. In this project, the goal is to break the cycle of poverty, malnutrition and oppression of the Batwa communities by supporting Batwa women to become more self-reliant through sustainable agriculture initiatives.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

The creation of the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda forced migration of the indigenous Batwa people off their native land resulting in increased oppression, food insecurity, extreme poverty and poor health outcomes for the Batwa.

Throughout history, the Batwa have lived peacefully in the forest hunting and foraging for their sustenance. Since their violent removal from Bwindi, they have been caught in a cycle of poverty and abuse. They were given no rights to land and have no knowledge or tradition in farming. The Batwa, once hunter-gatherers with little to no knowledge in agricultural techniques, are now forced to live and adjust to a modern agrarian society.

Throughout history, the Batwa have lived peacefully in the forest hunting and foraging for their sustenance. Since their violent removal from Bwindi, they have been caught in a cycle of poverty and abuse. They were given no rights to land and have no knowledge or tradition in farming. The Batwa, once hunter-gatherers with little to no knowledge in agricultural techniques, are now forced to live and adjust to a modern agrarian society.

The Batwa women and girls are some of the most marginalized people in Africa. Their population numbers have dropped dramatically, and since their eviction from the forest they have broadly been reduced to the status of landless squatters with few opportunities to make their own livelihoods. The whole Batwa community, especially women and children, has been devastated by extreme poverty, sexual exploitation and substance abuse. They have suffered some of the most severe health outcomes and fall far below the average health outcomes of typical Ugandans: Life expectancy is 28, compared with a Ugandan average of 53, and the 38 percent of Batwa children die before the age of five, compared with a Ugandan average of 18 percent. Average annual income is $25, compared with a Ugandan average of $420. Less than 0.5 percent of the Batwa population has a full secondary education, compared with 15 percent of Ugandans.

The Project

For years, DIG has cultivated a strong relationship with a local community-based organization, Global Batwa Outreach (GBO). A significant constraint to implementing this type of cooperative project has been the struggle to secure land and housing for the Batwa communities whose rights to their native land have been stripped by the government. Through the advocacy of GBO and other organizations these communities have now secured land rights.

In collaboration with women leaders in the Batwa community and GBO, DIG will provide experiential training in sustainable agriculture, nutrition, improved cooking practices and business record-keeping by developing three community demonstration gardens and 400 women-led home gardens directly benefitting 400 women and indirectly benefitting more than 1,200 Batwa women and girls and 800 men and boys in the families by breaking the cycle of poverty and food insecurity. This project will empower Batwa women to become self-reliant and to support their families.

DIG’s Farmer Field School model is based on the Garden Cycle (planning, preparing, seeds, planting and transplanting, maintenance, pest and disease, harvesting, and rotating). Workshops in cooperative business planning and record keeping will be incorporated in the project. Concurrently to the agriculture training, DIG and Global Batwa Outreach will follow DIG’s Seed-to-Plate nutrition curriculum to address specific nutritional life-cycle needs of the Batwa women through cooking demonstrations and nutrition training. Along with training, this project will support gardens at the individual household-level. Facilitators will train Batwa women and design and support their household gardens. The gardens will be designed to include local food preferences, changing climate patterns and innovative gardening techniques.

DIG’s Farmer Field School model is based on the Garden Cycle (planning, preparing, seeds, planting and transplanting, maintenance, pest and disease, harvesting, and rotating). Workshops in cooperative business planning and record keeping will be incorporated in the project. Concurrently to the agriculture training, DIG and Global Batwa Outreach will follow DIG’s Seed-to-Plate nutrition curriculum to address specific nutritional life-cycle needs of the Batwa women through cooking demonstrations and nutrition training. Along with training, this project will support gardens at the individual household-level. Facilitators will train Batwa women and design and support their household gardens. The gardens will be designed to include local food preferences, changing climate patterns and innovative gardening techniques.

This project will work specifically with Batwa women from three Batwa communities in Rwamahano, Kafuga and Kinyarushengye. The mothers of these households have expressed interest in learning sustainable agriculture skills and a willingness to invest both time and energy in this project. For the project, women have been identified through Global Batwa Outreach, the local community hospital and women community leaders. The households were chosen based upon three criteria: need (low food security, poverty and lack of education), percent of women per household and willingness to participate in the project.

DIG also anticipates the three communities will become resource hubs for other Batwa communities and the skills taught will be passed on. DIG’s cost-effective model is easily replicated as evidenced by the frequency the organization has seen in neighbor-to-neighbor transfer of skills. This ripple effect will impact another few hundred households potentially increasing the indirect beneficiaries to another 2,000 people, approximately 1000 more women and girls.

Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- What do you think about the conflict between the need to preserve endangered species and the needs of the indigenous people in the region?

- How do you think the combination of building gardens and training the Batwa how to develop and cultivate them will empower Batwa women?

- Why is it important that Batwa community leaders are involved in providing oversight and ownership

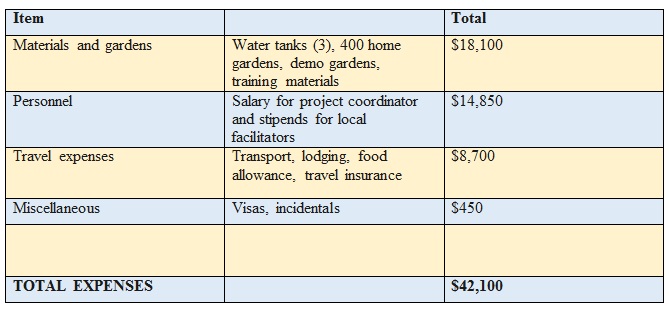

How the Grant Will be Used

DFW’s donation of $42,100 for one year will pay for the implementation of three community gardens and 400 women-led home gardens. The donation will cover a DIG Project Coordinator who will live on the site and three local facilitators (Women Leaders) from each of the Batwa communities, as well as costs for all garden and training materials, including tools, seeds, visual printouts and cooking materials. The project budget also includes travel costs, food and lodging for the Project Coordinator, and domestic transport for moving trainers between sites in a remote mountainous region with little to no public transportation available.

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love this project because it is well-researched and sustainable, and because of its focus on working with the Batwa population, its evidence of success, community buy-in, nutritional education, and its adaptation to individual environments.

Evidence of Success

DIG has developed demonstration garden sites with 15 HIV clinics/hospitals, 4 orphanages, 11 schools, and more than 35 community groups. Over 39,000 people have directly benefited from either an increased household income, greater diversity of nutritious produce consumption, or improved garden productivity at the household level. More than 2,000 individual home gardens have been directly supported by DIG with countless others developed by community members.

DIG has developed demonstration garden sites with 15 HIV clinics/hospitals, 4 orphanages, 11 schools, and more than 35 community groups. Over 39,000 people have directly benefited from either an increased household income, greater diversity of nutritious produce consumption, or improved garden productivity at the household level. More than 2,000 individual home gardens have been directly supported by DIG with countless others developed by community members.

Sustainability is at the core of DIG’s training programs. DIG works with locally based organizations to create its projects and identifies local leaders to implement the gardens. All DIG-assisted projects are developed with a model that makes the gardens self-sustainable within a short period of time. The gardens not only produce nutritious food, but also generate income, thus making the projects sustainable by the community without outside support.

Voices of the Girls

Before DIG, I could not afford to eat more than once a day. Now I have money, and I never need to buy vegetables from the market. Instead, people are coming here to buy them from us!

Before DIG, I could not afford to eat more than once a day. Now I have money, and I never need to buy vegetables from the market. Instead, people are coming here to buy them from us!

Rugina Abok (DIG Farmer in Kenya)

I really enjoy the social aspect of gathering with group members and working together, plus I never gardened before nor had a home garden. My family and I have saved so much money from harvesting vegetables at home and not buying them at the market, plus it is just fun!

Elaine Dabiré (DIG Farmer in Burkina Faso)

I think I am employed in my garden. It is like my self-employment!

Emily Achieng Obunga (DIG Farmer in Kenya)

I joined this group with a lot of resistance from my husband, my family members and my neighbors. They thought it was a waste of time but with my persistence all of them are changing. Through the sales of kales and saving income on veggies, that I now grow instead of buying, my daily income is increasing and I am really encouraged!

Benta Atieno (DIG Farmer in Kenya)

I have minimized my expenses on buying food because I can now grow my own.

Eunice Otieno (DIG Farmer- Young Mother)

About the Organization

Peace Corps volunteers Sarah Koch and Steve Bolinger started DIG in 2006 during their service in Senegal, West Africa. Inspired by Dr. Salif Sow, the head doctor of the infectious disease ward at the National Hospital Fann in Dakar, they began growing vegetables to feed malnourished and HIV positive patients. Prior to the garden, no fruits or vegetables were available for patients’ meals. A decade later, the garden produces on average nearly one ton of vegetables every month improving hundreds of meals for malnourished patients. The success of this project planted the seed for DIG, which still grows today.

Since its inception, DIG has specialized in promoting gardening and diet diversity in health facilities, schools and local households in African communities. Working in the area of sustainable agriculture, DIG, a 501(c)3 international non-profit, has achieved significant results from its programs in nearly a dozen countries. Its mission has remained true and unwavering: enabling vulnerable and HIV-affected communities to meet their own needs and improve their well-being through nutrition-sensitive and sustainable agriculture. DIG traditionally works with impoverished communities who are suffering from poverty, malnutrition, and disease. The communities DIG works with are predominately smallholder farmers. Eighty percent of the people DIG works with are women, with a majority living with HIV below the poverty line.

Since its inception, DIG has specialized in promoting gardening and diet diversity in health facilities, schools and local households in African communities. Working in the area of sustainable agriculture, DIG, a 501(c)3 international non-profit, has achieved significant results from its programs in nearly a dozen countries. Its mission has remained true and unwavering: enabling vulnerable and HIV-affected communities to meet their own needs and improve their well-being through nutrition-sensitive and sustainable agriculture. DIG traditionally works with impoverished communities who are suffering from poverty, malnutrition, and disease. The communities DIG works with are predominately smallholder farmers. Eighty percent of the people DIG works with are women, with a majority living with HIV below the poverty line.

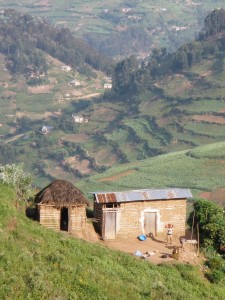

Where They Work

DIG’s service area is Sub-Saharan Africa: Uganda (Jinja, Kampala, and Kabale) and Kenya (Rongo and Homa Bay District, Nyanza). This project covers Kabale District, Uganda – near Bwindi Impenetrable Forest bordering Rwanda, Uganda, and DRC. Uganda is located in East Central Africa, west of Kenya, east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in an area slightly smaller than the state of Oregon. Its population is 37,101,745. Estimates for this country explicitly take into account the effects of excess mortality due to AIDS. This can result in lower life expectancy, higher infant mortality, higher death rates, lower population growth rates and changes in the distribution of population by age and sex than would be otherwise expected. The median age for a female is 15.7 years. The infant mortality rate is 59.21 deaths/1000 live births. Agriculture is the most important sector of the economy, employing more than two-thirds of the workforce.

A Closer Look at the Batwa People

For thousands of years the Batwa people dwelled in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, home to some of the greatest biodiversity on the planet. Some anthropologists estimate that pygmy tribes such as the Batwa have existed in the equatorial forests of Africa for 60,000 years or more. In addition to the Batwas, the forest sheltered a profusion of exotic plants and animals, including the endangered mountain gorilla. The Batwa survived by hunting small game using arrows and nets, and gathering plants and fruit. They lived in huts built of leaves and branches, and moved frequently in search of fresh supplies of food. The Batwa lived in harmony with the forest and its creatures and were known as “The Keepers of the Forest.”

For thousands of years the Batwa people dwelled in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, home to some of the greatest biodiversity on the planet. Some anthropologists estimate that pygmy tribes such as the Batwa have existed in the equatorial forests of Africa for 60,000 years or more. In addition to the Batwas, the forest sheltered a profusion of exotic plants and animals, including the endangered mountain gorilla. The Batwa survived by hunting small game using arrows and nets, and gathering plants and fruit. They lived in huts built of leaves and branches, and moved frequently in search of fresh supplies of food. The Batwa lived in harmony with the forest and its creatures and were known as “The Keepers of the Forest.”

In 1992, in a move to protect the 350 endangered mountain gorillas within its boundaries, the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest became a national park and World Heritage Site. The Batwa were evicted from their homeland. Since they had no title to the land, they were given no compensation. They were forced to try to forge a living in an unfamiliar, unforested land with no knowledge of agricultural methods. Many Batwa died during the early years of exile, and the tribe’s existence was devastatingly threatened.

Source Materials

Source: Batwa Development Program, http://www.batwaexperience.com/