Mission

Hope Through Health believes that everyone deserves access to high quality healthcare regardless of the latitude and longitude of their birthplace. The organization delivers effective, efficient, community-based healthcare in neglected settings like Togo, West Africa.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

Far too many women and children are lost to preventable deaths in Togo, West Africa, where one in 10 children die before age five and approximately 300 pregnant women die per 100,000 births. Maternal and child mortality rates are especially high in the dramatically underserved Kozah District of northern Togo. Much of this mortality and suffering could be avoided by ensuring access to the effective interventions known to prevent and treat the most commonly seen conditions.

Togo suffers some of the worst health indicators in Sub-Saharan Africa. The under-five mortality rate is 96 per 1,000 and the infant mortality rate is 62 per 1,000. The maternal mortality rate is almost 300 per 100,000. Utilization rates of public healthcare centers is extremely low. Currently, 7 out of 10 Togolese citizens lack access to adequate healthcare services. Approximately 62 percent of Togo’s population lives within 5 km of a public health clinic, but only 30 percent of the population uses these facilities, according to the Togolese Ministry of Health.

This lack of effective coverage is particularly devastating for pregnant women. The maternal mortality rate of 300 per 100,000 is well above the Millennium Development Goal target of 160 by 2015. Only 60 percent of deliveries that occur in Togo are facility-based. Among children, three preventable diseases – malaria, diarrhea and pneumonia – contribute to 47 percent of under-five mortality, with malaria alone contributing to 26 percent of deaths. Only 24 percent of children receive treatment for malaria within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms and only 24 percent of cases of diarrhea are treated with the recommended oral rehydration solution. Only 32 percent of children under age 5 with suspected pneumonia are taken to an appropriate health provider and only 41 percent of those receive antibiotics.

Geographic barriers, high costs, poor quality and perceived poor quality of care all contribute to low healthcare utilization and high mortality rates in Togo. With only one physician per 20,000 people, Togo lacks the functioning healthcare system, including personnel, supplies and training, required to deliver effective treatments to women and children.

The Project

This project will empower 25 female Community Health Workers (CHWs) to provide maternal and child healthcare to 3,500 pregnant women and children under age 5 in the Kozah District of northern Togo, leading to reduced rates of maternal and child morbidity and mortality.

This project will empower 25 female Community Health Workers (CHWs) to provide maternal and child healthcare to 3,500 pregnant women and children under age 5 in the Kozah District of northern Togo, leading to reduced rates of maternal and child morbidity and mortality.

The goals and methods of the project are:

1. To increase access to care, HTH will deploy CHWs to diagnose and treat the main killers of children under five – malaria, diarrheal disease, pneumonia and malnutrition – and to make referrals as necessary. They will also link pregnant women to routine preventive antenatal care and promote facility-based delivery. By providing care in the home and serving as facilitators to ensure pregnant women have access to essential care, this project will eliminate barriers that traditionally prevent women and children from receiving services.

2. To improve the timeliness of care, this project will create a rapid referral network and employ active CHW case finding. Prior to project launch, CHWs will be presented to the community through local religious and traditional structures. This will help CHWs earn the trust of their community and encourage community members to contact a CHW when a child falls sick or a woman becomes pregnant. CHWs will also spend a portion of each day going door-to-door to check for sick children and pregnant women. This two-pronged strategy will ensure that the majority of cases are diagnosed and treated within 24 – 72 hours of symptom onset. CHWs will also conduct follow-up visits at 24 and 48 hours post treatment to assess treatment effectiveness and refer for additional care if needed.

3. To ensure the quality of care, HTH will provide CHWs with extensive training including clear treatment algorithms, supplies and supportive supervision and oversight for community-based care. HTH will reinforce the maternal and child health services available at each community’s local government public clinic. Working in collaboration with the District Health Director, HTH will provide training for public health center staff, supplement the health center’s stock of medicines, supplies and equipment, and implement strong data management systems including a focus on using data for monitoring and improvement.

Together, these strategies provide an integrated community- and clinic-based approach to strengthen the health system in northern Togo. The goal is a reduction in preventable deaths and ultimately a decrease in maternal and child mortality over the long-term.

The four communities to be served by this project were selected by the District Health Director based on their high rates of disease and low rates of healthcare utilization. These communities are home to some of the poorest performing health centers in northern Togo, leaving the women and children in these communities without access to adequate healthcare services. All pregnant women and children under age 5 living in the target communities will be served by this project.

Questions for Discussion

1. How do you think this model of care will increase access to healthcare in this underserved region?

2. How do you think the use of CHWs will increase trust in the healthcare system?

3. What do you think the long-term impact of this project could be?

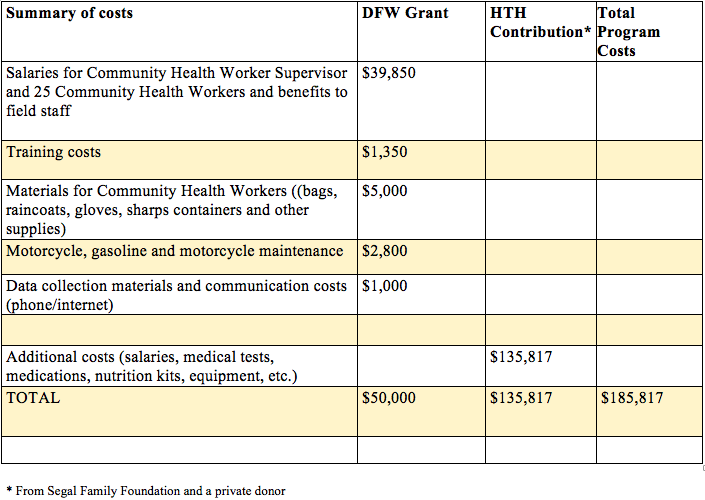

How the Grant Will be Used

DFW’s grant of $50,000 will support:

Personnel costs will include the full-time salaries of the new hires, including the Community Health Worker Supervisor and the 25 new CHWs, who will provide home-based care to women and children. Training costs include a per-diem to cover food and lodging for training participants and the costs of printing and duplicating of training materials. CHW Materials include bags, raincoats and other supplies. The motorcycle, gasoline and motorcycle maintenance will allow the CHW Supervisor to support and supervise CHWs in the field. Monitoring, evaluation and quality improvement materials will allow for data collection and communication among CHWs, the CHW supervisor and public health center staff.

The project has a total cost of $185,817. HTH has received funding from the Segal Family Foundation and one private donor to cover $135,817 of the cost of this project.

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love the focus on reducing maternal and child mortality and morbidity, as well as the three-pronged goal that has the potential to make an impact far beyond the scope of the project.

Evidence of Success

Since 2004, HTH has saved thousands of lives by delivering high-quality healthcare services to people living with HIV/AIDS through five health clinics in northern Togo. Through this process, HTH learned that building effective healthcare delivery systems, that can be replicated by the public sector, can help to ensure that services reach those most in need. HTH currently provides comprehensive HIV/AIDS services, including antiretroviral therapy, voluntary counseling and testing, hospitalizations, home visits from CHWs, prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV and pediatric HIV care. HTH believes that the same approach that has successfully delivered HIV/AIDS care, a focus on improved access, timeliness and quality, can be utilized to improve maternal and child health services in Togo.

Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of a package of integrated facility-based and community-based services in decreasing childhood morbidity and mortality in West Africa. A program launched by Project Muso in Mali, in partnership with the Malian Ministry of Health, implemented a package of key interventions similar to those proposed for this project, including:

- Use of CHWs to provide home-based care, including diagnosis and treatment of malaria in children under 5, referrals for other illnesses, conducting 24 hour and 48 hour follow ups, and referrals for pregnant women,

- Removal of health center user fees,

- Improvement of public clinic infrastructure,

- Training of healthcare workers at MOH health centers, and

- Creation of rapid referral network among religious and community organizations.

Over three years, child mortality in the intervention area decreased from 155 per 1,000 to 17 per 1,000. Prevalence of fever in children under age 5 in the last two weeks decreased from 38 percent in 2008 to 23 percent in 2011. Effective antimalarial treatment within 24 hours among children under age 5 with a fever increased from almost 15 percent at baseline to 28 percent after three years. Given the success of this approach in Mali, HTH hopes to achieve comparable reductions in child morbidity and mortality by implementing similar activities in Togo. HTH also plans to use CHWs to improve maternal health.

HTH has a proven record of success in providing healthcare services. HTH is one of the only international organizations with a sustained presence in northern Togo. With 10 years of experience, strong relationships with the Ministry of Health and a proven track record, HTH is best positioned to seize this opportunity and catalyze improvements in the health of Togo’s women and children.

Voices of the Girls

From HTH Community Health Workers:

From HTH Community Health Workers:

“As a Community Health Worker I will make my father proud by contributing to our family, I will provide for myself and my baby and I will save the lives of small children in my community. I am very proud.” – Florence Akawa, Community Health Worker

“I am excited to see what we learned at HTH’s maternal and child health training produce something real in our community. We are waiting for that moment.” –Véronique Latta, Community Health Worker

“Kpindi will change, that is a given. Not only will less children die, but more parents will be protected from poverty.” – Rebecca Tchotchokou, Community Health Worker

“I am motivated to be a CHW because this work is about life or death. If we do not do something, children will continue to die. The child of another person is not just their child – it is the community’s child. This affects all of us.” – Prénam Agbelou, Community Health Worker

About the Organization

Hope Through Health (HTH) was created in 2004 by US Peace Corps Volunteers, Kevin Fiori Jr. and Dr. Peter Davenport, in collaboration with a community-based association of people living with HIV/AIDS, called Association Espoir pour Demain (AED Lidaw). After searching in vain for an international organization to partner with AED-Lidaw, HTH was founded to assist AED-Lidaw in providing HIV care and treatment services in northern Togo, where these services were not yet available. When HTH began working in Togo in 2004, AED-Lidaw consisted of 70 individuals. Since then, the organizations have collaborated to build a community-led model that in 2014 provided comprehensive healthcare services to 1,712 adults and 167 children living with HIV/AIDS and employed more than 50 community members across five health center sites in northern Togo. HTH’s model for HIV/AIDS care is more than a medical program – it is a local response to the pandemic initiated, implemented and sustained by HIV-positive individuals living in extreme poverty.

Where They Work

Togo is located in Western Africa, bordering the Bight of Benin (on the Gulf of Guinea), between Benin and Ghana. It occupies an area slightly smaller than West Virginia. The climate is hot and humid in the south and semiarid in the north. The country can experience periodic droughts. Current environmental concerns include deforestation attributable to slash-and-burn agriculture and the use of wood for fuel; water pollution that presents health hazards and hinders the fishing industry; and air pollution increasing in urban areas.

Togo is located in Western Africa, bordering the Bight of Benin (on the Gulf of Guinea), between Benin and Ghana. It occupies an area slightly smaller than West Virginia. The climate is hot and humid in the south and semiarid in the north. The country can experience periodic droughts. Current environmental concerns include deforestation attributable to slash-and-burn agriculture and the use of wood for fuel; water pollution that presents health hazards and hinders the fishing industry; and air pollution increasing in urban areas.

French Togoland became Togo in 1960. Military rule was installed in 1967. Despite the facade of multi-party elections instituted in the early 1990s, the government was largely dominated by President Eyadema, whose Rally of the Togolese People (RPT) party has been in power almost continually since 1967 and its successor, the Union for the Republic, maintains a majority of seats in today’s legislature. Upon Eyadema’s death in February 2005, the military installed the president’s son, Faure Gnassingbe, and then engineered his formal election two months later. Democratic gains since then allowed Togo to hold its first relatively free and fair legislative elections in October 2007. After years of political unrest and condemnation from international organizations for human rights abuses, Togo is finally being re-welcomed into the international community.

The risk of major infectious disease remains high in Togo, and nearly 5 million of the country’s 7.5 million people lack access to adequate heath care.

A Closer Look:

According to the World Health Organization, there were about 198 million cases of malaria in 2013. Most deaths occur among children living in Africa, where a child dies every minute from malaria. Malaria mortality rates among children in Africa have been reduced by an estimated 58 percent since 2000, but children younger than age 5 still account for 78 percent of malaria deaths.

Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites, which are transmitted to people through the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes. About 90 percent of malaria deaths occur in Africa. African Anopheles mosquitoes have a long lifespan and are particularly prone to biting humans. Symptoms of malaria mimic those of the flu – high fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, fatigue and nausea. Symptoms can begin 10 days – 4 weeks after infection.

According to UNICEF, malaria infection during pregnancy is associated with severe anemia and other illnesses in the mother and can contributes to low birth weight – one of the leading risk factors for infant mortality and less than optimal growth and development. Malaria also contributes to anemia in children, which can impact growth and development. Malaria is treatable, but children should receive treatment soon after the onset of symptoms. Early treatment is the key. The longer that treatment is delayed, the more serious and life-threatening the condition may become.

Learn more key facts about malaria in this WHO video.

Source Materials

Hope Through Health, The CIA World Factbook, UNICEF, WHO