Mission

The mission of Sacred Valley Health is to promote health in the rural, underserved communities of Peru’s Sacred Valley through education, access, and women’s empowerment.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

According to a 2014 Peruvian Ministry of Health survey, 18 percent of children in the Cusco region are chronically malnourished. Over half exhibit stunted growth, are underweight, or both, according to World Health Organization standards. In the same communities, 55 percent of children under five are anemic, and many experience chronic illness, learning delays, and developmental problems.

Malnutrition is a problem in this area for a number of reasons. First, the geographic isolation of communities in the Cusco region presents significant obstacles to proper nutrition. There is limited access to nutrient-rich foods and the extreme altitude in some communities makes it difficult to grow a variety of crops, apart from potatoes. Also, there is a substantial lack of nutrition education. In a recent survey, 36 percent of mothers were unable to identify foods appropriate for a six-month old baby. Parents are unaware of the importance of a balanced diet and community members lack training on how to successfully grow a wider selection of food at high-altitude.

The Project

Sacred Valley Health (SVH) promotes improved health in the underserved rural communities of Peru’s Sacred Valley. SVH operates in the high-altitude Ollantaytambo District, Andean communities where the lack of education, geographic isolation, and economic conditions severely affect the nutritional status of children. By instituting nutrition education, SVH breaks the cycle that perpetuates chronic illness, learning delays, and developmental problems, thus transforming the lives of children and families. By adhering to three pillars – education, access, and empowerment – SVH transforms the lives of its employees, Community Health Workers, and the community. By empowering and employing women, SVH decreases the effects of poverty and brings gender equality to a society still rooted in male dominance.

Sacred Valley Health (SVH) promotes improved health in the underserved rural communities of Peru’s Sacred Valley. SVH operates in the high-altitude Ollantaytambo District, Andean communities where the lack of education, geographic isolation, and economic conditions severely affect the nutritional status of children. By instituting nutrition education, SVH breaks the cycle that perpetuates chronic illness, learning delays, and developmental problems, thus transforming the lives of children and families. By adhering to three pillars – education, access, and empowerment – SVH transforms the lives of its employees, Community Health Workers, and the community. By empowering and employing women, SVH decreases the effects of poverty and brings gender equality to a society still rooted in male dominance.

SVH addresses malnutrition by disseminating targeted nutrition education via specialized, female Community Health Workers (CHWs). Economic and leadership opportunities are made available to women through employment in a nutrition-focused train-the-trainer (docente) program. The primary outcomes include employment of eight women as docentes, training 30 women as Advanced Nutrition CHWs, increasing community member knowledge about best practices around nutrition, and eventually decreasing the number of malnourished children. SVH uses an evidence-based model, applying recommendations from the World Health Organization. The idea for the Advanced Nutrition Certification Program was generated by requests from women in the communities, especially mothers, for more education and materials specific to nutrition.

Two of the 14 communities SVH serves have no road access, and of those that do, few have regular or reliable transportation. Only three of the 14 communities have local access to secondary schools. Forty-one of the 44 current CHWs are women. Sixty percent are illiterate and speak only Quechua, the ancient indigenous language. The median income per household among the CHWs i s about $30 per month. SVH offers the opportunity for these women to become educated health leaders in their communities. There are approximately 1,000 women ages 12 and older, approximately 400 children under five years of age, and approximately 700 total households in communities served by SVH. This program also impacts young girls and women who see these docentes and CHWs stepping into leadership positions. By redefining existing gender roles in their communities, they are paving the way for the next generation of female leaders.

s about $30 per month. SVH offers the opportunity for these women to become educated health leaders in their communities. There are approximately 1,000 women ages 12 and older, approximately 400 children under five years of age, and approximately 700 total households in communities served by SVH. This program also impacts young girls and women who see these docentes and CHWs stepping into leadership positions. By redefining existing gender roles in their communities, they are paving the way for the next generation of female leaders.

By employing Advanced Nutrition Docentes, SVH will have the opportunity to provide economic empowerment to women living in extreme poverty. As young girls watch their mothers’ paths to empowerment unfold, they learn to dream bigger than ever before. By teaching mothers about nutrition, they are empowered to be better decision-makers for their families and can raise healthier children and build stronger communities.

There are six key anticipated outcomes of this two-year program:

- To hire eight Advanced Nutrition Docentes and train them in leadership skills, adult learning techniques, and advanced nutrition education

- To train and certify 30 Advanced Nutrition CHWs

- To increase community member knowledge about the benefits of and implementation of good nutritional practices

- To increase awareness about existing nutritional practices in communities that are beneficial and should be preserved

- As a long-term outcome, SVH aims to decrease the number of children under 5 who are underweight, stunted, and/or anemic

- As a long-term outcome, this project will provide more opportunities for women to be promoted within the organization and ultimately, climb out of poverty.

SVH’s project centers on a “train the trainers” model. It is designed to directly serve two different groups of people. First, over the course of the two years, it will provide social and economic empowerment opportunities to eight impoverished, low-literacy, indigenous women who are hired and trained as docentes. Second, it provides a targeted skillset and an advanced educational opportunity to 30 CHWs trained in Advanced Nutrition. In year one, 20 women will be directly served and 1,000 will be indirectly impacted. In year two, the expectation is that 18 women will be directly served and 1,000 will be indirectly impacted. All project materials and implementation are tailored to the specific population served (indigenous Andean communities).

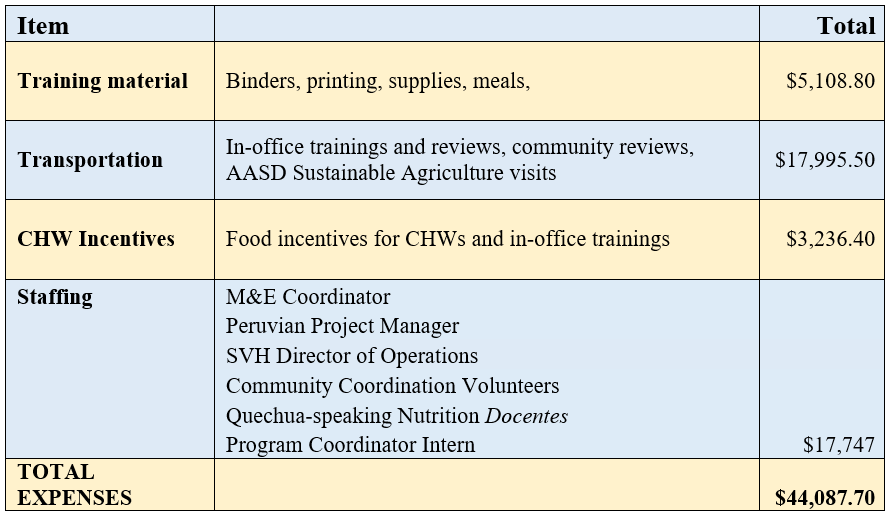

DFW’s grant includes funding for the following:

DFW’s grant includes funding for the following:

- Training Materials and Supplies: This includes materials used to train docentes, CHWs, and community members. Nutrition-focused training resources for a low-literacy population will be developed and used with docentes and CHWs at in-office trainings. CHWs will also be equipped with supplies to provide nutrition instruction to community members as well as community nutrition demonstrations. Docentes and CHWs are fed nutritious, balanced meals at each training.

- Transportation: SVH operates in geographically isolated areas of the Andes. To encourage attendance at trainings and improve attrition rates, SVH provides transportation for docentes and CHWs for all office trainings through contracted van services. To facilitate in-community review, SVH also allocates funds to allow docentes or coordinators to travel to communities to provide one-on-one time with CHWs.

- CHW Incentives: CHWs participate in SVH programs on a voluntary basis. They are compensated for their time and participation with nutritional food incentives, including meat, fresh fruits and vegetables, and whole grains.

- Staffing Expenses: Providing employment opportunities for local women is a primary objective of this project. The majority of staffing expenses are for a local program manager and the docentes, who will be experienced CHWs employed for the first time, specifically for this project. The other significant portion of staffing expenses is for a staff member to ensure data is appropriately gathered and analyzed to evaluate the project’s impact.

Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- Why do you think the “train the trainer” model is key to SVH’s success?

- In addition to enhanced health, what other benefits do you think children will see and feel?

- How do you think this project will change the current health system?

How the Grant Will be Used

Dining for Women’s two-year grant of $44,087.70 allows Sacred Valley Health to provide the necessary training, transportation, CHW incentives, and staffing.

Year 1 Direct Impact: 20; Indirect Impact: 1,000

Year 2 Direct Impact: 18; Indirect Impact: 1,000

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love this project because it is located in an area of great need, and it addresses nutrition issues through early intervention. Sacred Valley Health’s programming complements and strengthens the local health care system and draws Community Health Workers from the communities they serve.

Evidence of Success

CHWs have performed more than 4,000 educational house visits in at-risk Peruvian communities. In addition to widely increasing the amount of health education available, SVH has also provided numerous leadership opportunities to women by educating them as CHWs and by employing them as docentes, coordinators, and managers. Since its start in 2012, SVH has trained 68 different CHWs, 93 percent of whom have been women. Forty-four of those 68 CHWs are still participating in the program. Through CHW satisfaction surveys, improvements to curriculum, and modifications to CHW selection process, SVH has cut its attrition rate in half, from 36 percent in 2013 to 18 percent in 2016.

SVH has received competitive one-time, repeat, and multi-year funding from a variety of competitive funders, including the Conservation Food and Health Foundation, the Arcadia Charitable Trust, the Hope for Poor Children Foundation, the Weyerhaeuser Family Foundation, and the AMB Foundation. In addition, SVH has established relationships with many US universities that partner with SVH for health service trips, including State University of Upstate New York (SUNY), University of Rochester, Lafayette College, Clemson University, and the University of Washington.  Not only have these experiences led to lasting, long-term relationships, but they continue to generate publicity for SVH.

Not only have these experiences led to lasting, long-term relationships, but they continue to generate publicity for SVH.

In the fall of 2016, SVH was approached by Microsoft to participate in a high-impact technology project with Microsoft US and Microsoft Peru. SVH was selected due to its positive reputation of working with the local community. This partnership has the potential to provide incredible publicity in the coming months, as it is the first NGO/Microsoft partnership of its kind in South America.

Currently, there are no other organizations working in the same capacity as SVH in the Ollantaytambo District.

Voices of the Girls

“When I started out as a promotora (CHW), I had no experience. I would spend all day out in the mountains with my sheep. Even when there would be community assemblies, I never stood up to speak. I was shy and embarrassed to talk to people. Now I’m an Ayni Wasi (SVH) employee. I am grateful to Ayni Wasi for teaching me and for training me as a leader. I think I’m most grateful for becoming a leader. Now I’m a working woman. If it weren’t for Ayni Wasi I would still just be working at home. Now I know things. I am grateful on behalf of my family who I’m serving as a promotora, and my community, too.”

Berta Quin Ugarte, CHW with SVH since 2013

“Parents don’t know how to feed their kids well. They want to. These are good people here, willing to learn, quick to learn. They just need the tools and the education.”

Doctor at the local government clinic

About the Organization

In 2010, Keri Baker and two other volunteers established Awamaki Health, a branch of Awamaki, an Ollantaytambo, Peru-based organization focused on fostering women’s empowerment through the textile industry. Awamaki Health placed health volunteers within local government clinics, provided public health classes, led fluoride campaigns in school, and hosted other community outreach programs. In September 2011, based on community input, Baker launched a mobile health unit to address the healthcare needs of the rural communities surrounding Ollantaytambo, which, according to recent census data, make up approximately 70 percent of the District’s 9,851 inhabitants. As the program grew and evolved, it became apparent that there was a need for a local, independent, health-focused NGO with an emphasis on sustainability.

Awamaki Health branched off in early 2012 to become Sacred Valley Health to promote health in Andean Peru via a community health worker program, improving health through education, access, and women’s empowerment. The program complements and strengthens the local health care system, which is very short on funding and personnel. Working in partnership with outpost clinics run by the Ministry of Health, SVH trains community health workers who live in the communities they serve. With a dedicated staff and team of volunteers, SVH began recruiting and training community health workers in the Ollantaytambo District to launch a frontline health worker program. For two years the program focused on developing relationships with local communities through integrity, reliability, and community involvement. In 2014, SVH began training a 2nd cohort of community health workers.

Awamaki Health branched off in early 2012 to become Sacred Valley Health to promote health in Andean Peru via a community health worker program, improving health through education, access, and women’s empowerment. The program complements and strengthens the local health care system, which is very short on funding and personnel. Working in partnership with outpost clinics run by the Ministry of Health, SVH trains community health workers who live in the communities they serve. With a dedicated staff and team of volunteers, SVH began recruiting and training community health workers in the Ollantaytambo District to launch a frontline health worker program. For two years the program focused on developing relationships with local communities through integrity, reliability, and community involvement. In 2014, SVH began training a 2nd cohort of community health workers.

In 2015, in an effort to increase sustainability, SVH staff launched a train-the-trainer (docente) program. This program focused on employing the most successful CHWs to train the next generation of CHWs. In 2016, SVH recruited 40 more CHWs to further program reach and continue the mission of improving health outcomes within Peru’s Sacred Valley. As SVH has evolved, it has continually expanded the presence of local, female leadership in its onsite office by offering employment opportunities to CHWs and shaping program changes around input from local women at all levels.

SVH currently works in 14 rural communities around Ollantaytambo, Peru. CHWs are trained in disease prevention, health promotion, and first-aid skills. The curriculum uses a low-literacy format as most members of the team have limited reading and writing ability. The current areas of focus are respiratory disease, parasitic diarrheal disease, and malnutrition. In addition to providing health education and nutrition screening (height, weight, and anemia testing), SVH distributes multivitamins to children from six-months-old to five years of age as well as to pregnant and lactating women. The Vitamin Distribution Program allows SVH to identify and track children who are stunted by World Health Organization standards or missing vaccines. CHWs educate community members in disease prevention and provide high-risk families with intensive case management support via home visits. SVH is also in the pilot year of a Women’s Health Program, focusing on decreasing maternal-child morbidity and mortality and providing education on family planning and domestic violence.

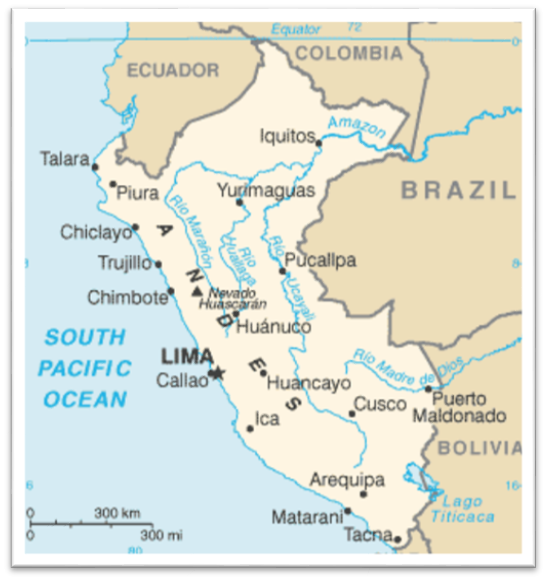

Where They Work

Sacred Valley Health’s office is based in the small historic town of Ollantaytambo, Peru, located between the Incan capital of Cusco and Machu Picchu, in the heart of Peru’s Sacred Valley. The service area focuses on the 30 rural communities in the Ollantaytambo District, which, according to recent census data, make up approximately 70 percent of the District’s nearly 10,000 inhabitants.

Peru is almost twice the size of Texas, with a varied climate depending upon region. Its population is slightly more than 31 million. Peru’s urban and coastal communities have benefited much more from recent economic growth than rural, Afro-Peruvian, indigenous, and poor populations of the Amazon and mountain regions. The poverty rate has dropped substantially during the last decade but remains high at about 30 percent in urban areas and more than 55 percent in rural areas. Many poor children temporarily or permanently drop out of school to help support their families. About a quarter to a third of Peruvian children ages 6 – 14 work, often putting in long hours at hazardous mining or construction sites.

Ancient Peru was the seat of several prominent Andean civilizations, most notably that of the Incas whose empire was captured by Spanish conquistadors in 1533. Peru declared its independence in 1821. Peru’s first democratically elected president of indigenous ethnicity took office in 2001. Former army officer Ollanta Humala Tasso was elected president in June 2011, and carried on the sound, market-oriented economic policies of the three preceding administrations. Poverty and unemployment levels have fallen dramatically in the last decade, and today Peru boasts one of the best performing economies in Latin America. Pedro Pablo Kuczynski Godard won a very narrow presidential runoff election in June 2016.

A closer look at food security and the cycle of malnutrition in women

There are an estimated one billion undernourished people in the world, and every year three million children die under age 5 from malnutrition. Micronutrient deficiencies lead to poor growth, blindness, susceptibility to disease, and even death. The causes of world hunger include poverty, population growth, and environmental issues such as climate change.

There are an estimated one billion undernourished people in the world, and every year three million children die under age 5 from malnutrition. Micronutrient deficiencies lead to poor growth, blindness, susceptibility to disease, and even death. The causes of world hunger include poverty, population growth, and environmental issues such as climate change.

Unfortunately, women often take the brunt of food insecurity, especially where men are the primary decision makers and earners. For instance, in developing nations women farmers often have yields that are 20 to 30 percent lower than their male counterparts because they have less access to improved seeds, fertilizers, and equipment. In some areas, women farmers practice shorter fallow periods than men because they have insecure access to land. In sub-Saharan Africa, women are often the only caregivers for family members suffering from HIV/AIDS and other diseases, which leaves them less time to grow food.

Cultural norms also play a role in women’s disadvantageous relationship to food. In some countries women can only eat after all the men and children have eaten. This chronic “food discrimination” often results in illness and malnourishment. When there is a crisis, women are often the first to sacrifice their food in order to protect their children. In a further spiraling of unfortunate events, this in turn results in women giving birth to underweight babies who are at much greater risk of an early death. If the baby survives and is female, she is at higher risk for being stunted and continuing the cycle.

Food security and gender equality are inextricably linked, and the key to unlocking better and regular nutrition for all is education. Results of a study show that educating women contributed to a 43 percent reduction in child malnutrition versus 26 percent for food availability alone. Studies from Africa further confirm these findings, which show that children of mothers who have at least five years of education are 40 percent more likely to live beyond age five.

Source Materials

https://www.wfp.org/our-work/preventing-hunger/focus-women/women-hunger-facts

http://www.fao.org/gender/gender-home/gender-programme/gender-food/en/

https://reliefweb.int/report/world/women-are-pivotal-addressing-hunger-malnutrition-and-poverty

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3226027/http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2013/mar/05/women-secret-weapon-food-security

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/vanessa-thevathasan/the-impact-of-food-insecurity_b_5999772.html

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pe.html