Mission

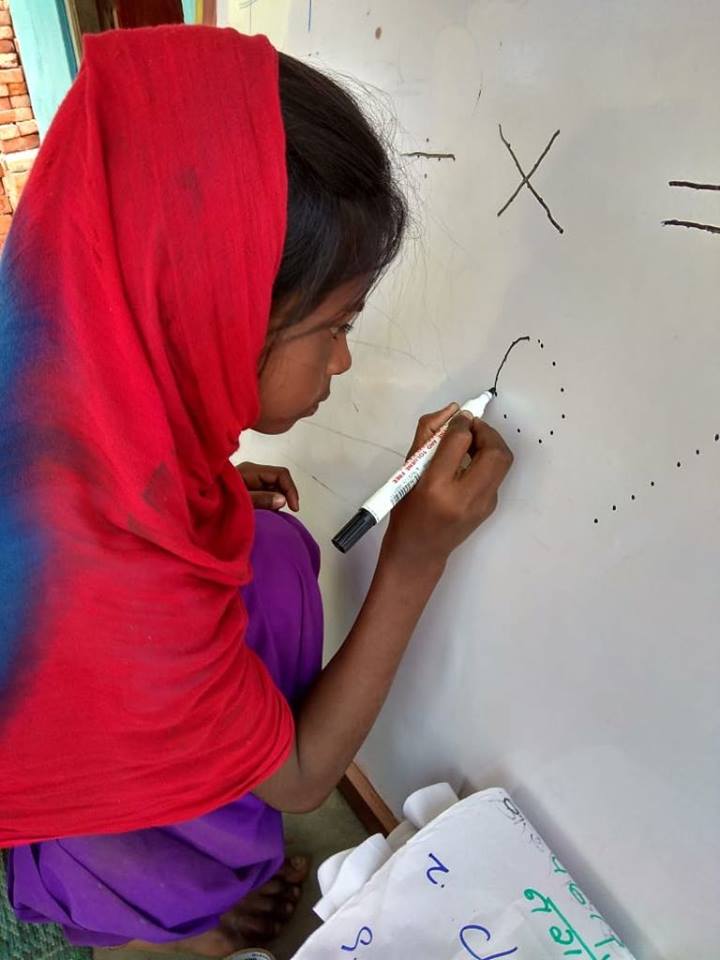

Street Child (SC) helps children living in poverty in the world’s toughest places go to school and learn to read and write for a brighter future. The Breaking the Bonds project helps adolescent girls in remote areas of Nepal achieve functional literacy and numeracy, make sustainable transitions into meaningful employment, and develop confidence and awareness of their rights to reduce prejudice and sexual violence.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

One of the poorest and least developed countries in the world, Nepal is listed at 144 out of 188 countries on the United Nations Human Development Index. Today there are an estimated 300,000 to 2 million people in modern slavery or debt bondage. Bonded labor, also known as debt bondage and peonage, happens when people give themselves into slavery as security against a loan or when they inherit a debt from a relative. It can be made to look like an employment agreement but one where the worker starts with a debt to repay – usually in brutal conditions – only to find that repayment of the loan is impossible. Then, their enslavement becomes permanent. In 2008, the Government of Nepal criminalized bonded labor and initiated rehabilitation programs to free people from debt bondage. However, the practice continues to be widespread. In fact, the policy has been implemented haphazardly and has actually made marginalized communities even more vulnerable.

One of the poorest and least developed countries in the world, Nepal is listed at 144 out of 188 countries on the United Nations Human Development Index. Today there are an estimated 300,000 to 2 million people in modern slavery or debt bondage. Bonded labor, also known as debt bondage and peonage, happens when people give themselves into slavery as security against a loan or when they inherit a debt from a relative. It can be made to look like an employment agreement but one where the worker starts with a debt to repay – usually in brutal conditions – only to find that repayment of the loan is impossible. Then, their enslavement becomes permanent. In 2008, the Government of Nepal criminalized bonded labor and initiated rehabilitation programs to free people from debt bondage. However, the practice continues to be widespread. In fact, the policy has been implemented haphazardly and has actually made marginalized communities even more vulnerable.

Within Nepal, the Musahar caste is among the world’s most politically marginalized, economically exploited, and socially humiliated groups, ranking 129 out of 130 castes in terms of Human Development Indicators. Despite the abolishment of the caste system in Nepal many decades ago, Musahars continue to be marginalized and face discrimination both by institutions and civil society. They cannot afford school or access employment due to extreme poverty and entrenched practices of oppression, as well corrupt government officials, teachers, and employers who isolate them due to their untouchable (a term used to refer to the multiple castes at the lowest levels in the caste hierarchy in India and Nepal) status. They are physically segregated from the general population and live in separate clusters or colonies on the peripheries of other areas.

Musahars live in extreme poverty, with an average wage of $27 per month versus a national average of $727 per month. They are landless, born into bonded labor, and most are in debt, paying an average interest rate of 40 percent. They live in hard-to-reach, remote areas which, along with their caste status and linguistic segregation, leave them isolated and systematically excluded from social, political, economic, and legal structures such as education, employment, and voting. Eighty percent of Musahars lack voter identification, restricting political participation and erasing any incentive for politicians or policymakers to address their needs.

Musahars live in extreme poverty, with an average wage of $27 per month versus a national average of $727 per month. They are landless, born into bonded labor, and most are in debt, paying an average interest rate of 40 percent. They live in hard-to-reach, remote areas which, along with their caste status and linguistic segregation, leave them isolated and systematically excluded from social, political, economic, and legal structures such as education, employment, and voting. Eighty percent of Musahars lack voter identification, restricting political participation and erasing any incentive for politicians or policymakers to address their needs.

Marginalized by gender, ethnicity, and class, women and girls bear the brunt of this oppression. Forced into early marriage or bonded labor to help pay off huge family debts, most Musahar girls are married by age 10 and have 2 – 5 children by age 15. Educational outcomes are dire. Set in the dominant Nepali rather than the regional vernacular Maithili, the teaching curriculum excludes Musahar linguistically, and girls face frequent abuse from teachers who see them as uneducable. As a result, only four percent of Musahar girls are in school after age four, and 100 percent are out of school by age 10. Illiteracy among Musahar women is at 96 percent. That, combined with discrimination, keeps Musahars unemployed.

Musahar women are trapped. They are often abused for entering other communities, yet endure physical, psychological, and sexual harm from within their own community due to high levels of alcohol and substance abuse among men. Excluded from water, sanitation, reproductive, and hygiene services, they suffer lower health outcomes than men. One out of three women do not have a birth certificate so they cannot access citizenship or other legal structures. For Musahar women and girls, systemic, top-down racial discrimination and gender oppression (including gender-based violence) intersect to leave them doubly marginalized by caste and sex.

The Project

Street Child US aims to change the social and political landscape for Musahar women through a multi-pronged intervention called Breaking the Bonds, which has been designed in conjunction with local organizations and with extensive input from the Musahar themselves. The intervention supports women living in extreme poverty, and it addresses Musahar girls’ need for education, economic training and opportunities, and leadership and rights awareness training and advocacy. It also works to create attitudinal change and sustainably promote gender equality – including preventing gender-based violence. This is a core element of the program, crucial for achieving meaningful change in access to education and leadership, and for promoting true impact for the futures of Musahar girls and their families.

Street Child US aims to change the social and political landscape for Musahar women through a multi-pronged intervention called Breaking the Bonds, which has been designed in conjunction with local organizations and with extensive input from the Musahar themselves. The intervention supports women living in extreme poverty, and it addresses Musahar girls’ need for education, economic training and opportunities, and leadership and rights awareness training and advocacy. It also works to create attitudinal change and sustainably promote gender equality – including preventing gender-based violence. This is a core element of the program, crucial for achieving meaningful change in access to education and leadership, and for promoting true impact for the futures of Musahar girls and their families.

DFW’s grant allows 187 girls ages 15 – 18 to participate in the Breaking the Bonds program to achieve functional literacy and numeracy, make sustainable transitions into meaningful enterprise or employment opportunities, and develop confidence and awareness of their rights to reduce prejudice and sexual violence. The project will be available in Nepal’s Terai region in the districts of Dhanusha, Mahottari, and Siraha.

Girls will participate in the program for a total of 15 months, with classes held in community spaces by 40 Community Educators recruited and trained by SC. The program will create sustainable, systemic change for future generations and improve the lives of this immediate cohort of beneficiaries via three interlinked components:

Girls will participate in the program for a total of 15 months, with classes held in community spaces by 40 Community Educators recruited and trained by SC. The program will create sustainable, systemic change for future generations and improve the lives of this immediate cohort of beneficiaries via three interlinked components:

Accelerated Learning – This improves functional literacy and numeracy for both self-empowerment and to access to the job market. This 9-month program will use a tailored curriculum to provide functional literacy and numeracy skills needed for training and employment opportunities. Classes will be delivered by 40 teachers recruited locally to ensure they can understand the local context, as well as the specific challenges these girls face, and can deliver the curriculum in the regional language of Maithili. Educators will work closely with schools and especially male teachers over several years, to coach them towards changing attitudes towards Musahar girls’ capacity to learn and their right to an education. Girls who are of school-going age will be supported to transition into formal/mainstream education and continue with higher education if they wish.

UNICEF research shows that even a single year of middle school education has the potential to increase a girl’s future earnings by up to 25 percent. Investment in girls’ education also has a multiplier effect: educated girls benefit from better family planning, better maternal health, and have healthier children who are more likely to remain in education themselves.

Enterprise and Employment – After completing the Accelerated Learning Program girls will move into one of two streams:

Transition to employment (anticipated 66 percent of girls): Girls will be supported through training and skill development in areas relevant to the local economy. At the end they will be matched to a suitable employer and helped to transition; or

Transition to employment (anticipated 66 percent of girls): Girls will be supported through training and skill development in areas relevant to the local economy. At the end they will be matched to a suitable employer and helped to transition; or- Enterprise development (anticipated 34 percent of girls): Beneficiaries will receive a cash grant of $200 to establish their own income stream, in growth areas such as cell phone repair. They will receive business skills and entrepreneurship training (business planning, budgeting, managing stock, business models etc.) and will be supported and mentored by SC to make the business profitable. Employer Training and Engagement is a crucial element within this strand. Teams of trainers will engage and train 675 businesses to employ Musahar people, with a focus on women. This will include education regarding inclusive hiring policies and practices, plus discussions which unpack and address prejudices and assumptions about Musahar women and their skills.

Life Skills and Rights Awareness – The isolation, violence, and discrimination experienced by Musahar girls undermines self-confidence and prevents them from accessing education and employment opportunities even when genuinely accessible. Workshops will take place three times weekly over 15 months, led by social workers. They will act as a safe space where girls can share experiences, build confidence and self-respect, and learn about important and relevant issues including gender-based violence and how to access political, economic, and legal rights such as citizenship cards. This builds inclusion and participation in economic, political, legal, and social systems including education, employment, voting, and personal and community-based decision-making. Workshops will address:

- Life skills in constructing, using and maintaining water and sanitation support, and confidence in accessing services and social networks;

- Personal and interpersonal skills, peer support and counseling for violence, and harmful gender norms;

- Government grants and services, including citizenship certificates, health and legal services and education scholarships.

This program encourages long-term, systemic change not only for an immediate cohort of marginalized women, but for future generations of both girls and boys. Improving literacy and numeracy and employment-related skills will lead to increased employment opportunities, which will in turn strengthen income security, increase income-earning capacity, and reduce poverty. Over time, repayment of debts enabled by greater income will break the cycle of debt bondage for girls and their families. Economic empowerment will lead to social and political empowerment and promote gender equality, including boosting Musahar girls’ awareness of their rights, confidence to access services and social networks, increased resilience and the ability to resist harm, and increased participation in decision-making. Seeing the benefits of education will also increase the appetite for education among Musahars.

Impact

Direct Impact – 187 girls, Indirect Impact – 3,000 families

UN Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- Why do you think it is critical that the Musahar be involved in the creation of this program?

- How do you think this program can help shed light on the plight of those trapped in a caste system?

- Although it is a 15-month program, Street Child considers it a long-term endeavor. Why?

How the Grant Will be Used

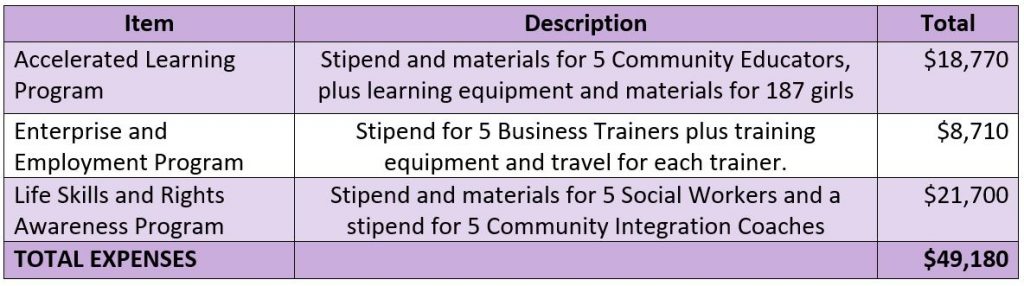

DFW’s grant of $49,180 for one year will fund the following:

Why We Love This Project/Organization

This project focuses on providing remedial learning, business skills, leadership opportunities and pathways to sustainable employment for girls ages 15 – 18 in the Musahar community. The Musahar live in hard-to-reach, remote areas which, along with their caste status and linguistic segregation, leave them isolated and systematically excluded from social, political, economic, and legal structures such as education, employment, and voting.

Evidence of Success

Since 2008, Street Child has allowed 200,000 children living in rural or marginalized areas of Africa and Asia to access education – with a 96 percent retention rate, at an average cost of $76 each. To achieve this, SC built 400 schools, refurbished 10,000 classrooms, gave out 22,000 business grants, provided 30,000 education support packages, and distributed hundreds of thousands of emergency relief packages.

Since 2015, SC has been a regular recipient of the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) annual match funding award (UK Aid Match), by which they match up to GBP1m (British Pound Sterling) in funds raised within a specified 3-month period. SC is the only organization to have been awarded this opportunity four times. In 2017, Innovations for Poverty Action evaluated SC’s education provision in Liberia and found it to be making a “statistically significant difference” in children’s learning, with six months in a SC classroom the equivalent of two standard years of learning in Liberia. SC was also the only operator to rank in the top three in both the highest outcomes and lowest cost categories.

Because of SC’s unique network in Sierra Leone – it is the only organization with a presence in every region – when Ebola struck in 2014, it was able to redeploy 1,600 teachers and social workers to provide health education to 250,000 rural villagers. There were only a handful of incidences of the disease afterwards.

Voices of the Girls

“We hope that with an education we can set up our own small businesses. The only shops we have in our village are liquor shops, run by men. By having our own businesses, we think we can set an example to our community and help change attitudes towards women and Musahars.”

- Students in Street Child’s accelerated learning program

“I was illiterate until I joined the class; I was not very sure but my husband convinced me to enroll in the program. He thinks that a literate person can have a better social standing. Now I am convinced that education changes life for better.”

- Bimala, 18-year-old student

“It is always the same – there is no development in our community. Every day is the same – we have to go the farm, because if we don’t go, we don’t eat. I’m scared that the government may turn up at any time and throw us off our land. There is no one to speak for us or to protect us. We can only speak for ourselves.”

- Chandrika, a Musahar woman

“I want a teacher for the children. I want a small candle factory for everyone in my community to work. I want the floor to be plastered around the water tap as it’s broken. Our children are thrown out of school if they have dirty clothes. Could someone from Street Child come to teach our children?”

- Maulana, a Musahar man

About the Organization

Street Child helps children living in poverty in the world’s toughest places gain an education and a brighter future. This organization believes all children have a right to a basic primary education and knows from experience that the first two years of secondary education are critical to consolidating literacy and numeracy. Therefore, the focus is on primary education and a strong transition to secondary, with mentoring for the first two years of the latter. SC helps children who are excluded from the education system or live where the system does not exist or has collapsed, including:

- Children living in rural villages where there are no schools

- Children living in refugee camps

- Girls, who are not considered educable by many communities

- Children orphaned by Ebola or conflict, who have no one to support their schooling

- Children whose education was disrupted by disaster or conflict

- Children living in extreme poverty, on less than $2 a day, who have no hope of reaching school

- Children shunned by their community, disabled children, street children, former child soldiers.

The organization was founded in the UK in 2008 by Tom Dannatt to fund a small back-to-school project for 100 war orphans in Sierra Leone. At the time, this was the poorest country in the world and had the lowest rates of literacy. SC now operates in nine countries across Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa with the backing of major funders and influencers such as UNICEF, USAID, and UfID.

Today, SC has seven overseas fundraising branches in Europe and the US that work together with the UK as a global federation. Street Child US was established in 2014 by US CEO Anna Bowden with investment from the UK office. Street Child has had 501c3 status since 2015 and has raised $800,000 from US foundations and individuals specifically towards programs in Nepal, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

The federation was small until 2015 when their ground-breaking work in response to the Ebola epidemic proved to be a turning point, gaining Street Child respect and recognition from public and major influencers such as UNICEF, DfID, and the United Nations Global Education Cluster (UN GEC). The GEC has since asked SC to bring its model to emergencies in Nepal, previously Boko Haram-held Nigeria, the Rohingya in Bangladesh, and Uganda’s refugees.

SC addresses the barriers to education via a holistic model comprising many components, including enterprise, school repair/construction, teacher training, child protection, community advocacy, self-esteem building and rights awareness, and emergency relief.

Partnerships are key to SC’s success. In each country, a local organization is identified that already has expertise and experience with the targeted population, with the goal of developing a long-term relationship with them. They become SC’s local implementation partner and take the Street Child name (Street Child of Nepal) into the community. SC then scales and capacity-builds that organization. Shorter-term partnerships are also created with organizations that have skill-sets critical to a particular intervention. SC brings partners together with other relevant stakeholders, such as the government, in a unique network. This ensures that interventions meet local and national government and funder priorities and are fully informed by local knowledge and context – crucial for sustainability and impact.

Where They Work

SC currently works in Sierra Leone, Monrovia and south-east Liberia, north-east Nigeria, Kampala and north-west Uganda, South Kivu plateau in Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Okhaldhunga and Terai regions of Nepal, southern Sri Lanka, and the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, and Kabul, Afghanistan.

Nepal is a landlocked country in the Himalayan region of South Asia that borders China and India and is very close to Bangladesh and Bhutan. The geography of Nepal is diverse, including plains, forested hills, and eight of the world’s 10 tallest mountains. The culture is also diverse: the 30 million residents come from a multitude of national origins and ethnic groups, including the Chhettri, Brahman-Hill, Magar, Tharu, and many others. As a result, fewer than half speak the official language of Nepali. Over 80 percent of the population are Hindu and 9 percent are Buddhist.

Nepal is considered one of the least developed countries in the world, with a quarter of its population living below the poverty line. Agriculture provides employment for almost two-thirds of the population, and in-roads have been made in harnessing Nepal’s considerable hydropower potential. However, the combination of challenging business and political climates plus the devastating 2015 earthquake set back economic development considerably.

Generally speaking, things are improving in Nepal – depending on where you live. For instance, there is a public and a private healthcare system that is improving in areas like the capital city of Kathmandu, but diarrhea, tuberculosis, and leprosy are still common in rural areas. Malnutrition continues to be a problem, with almost half of children under age five considered stunted. Education has also improved, yet few students complete their education, typically dropping out between primary and secondary school. The mountainous surroundings make transportation improvements throughout the country challenging.

Although the caste system is no longer legally supported, its history has left a permanent mark that defines today’s social stratification. This is evident by land ownership (the highest castes have historically owned the most land) as well as by physical traits and styles of dress and ornamentation. The symbols of ethnic identity are important to the Nepalese, and include distinctive forms of music, dance, and cuisine.

A Closer Look at the Plight of the Musahar

The 2 million members of the Musahar caste are among the most destitute and disadvantaged groups in the world. And because they have no power or voice to improve their situation, the Musahar suffer in silence. They are poor, humiliated, and illiterate. Musahar children who do go to school may face bullying from their classmates and even their teachers. These children are sometimes forced to sit separately in the back of the classroom and may not get to participate in group activities or lunch. They may even be denied drinking water. It is no surprise then, that the Musahar children are anxious to drop out of school to avoid this discrimination.

Musahar means “rat eaters,” a reference to this group’s traditional occupation of rat catchers. Although this population has indeed caught and eaten rats in the past, some individuals are beginning to go into nearby villages to work as agricultural laborers and day laborers. Regardless, they are well-known in the community as untouchables and therefore treated horribly by all other levels of society. Most of the families are victims of forced labor, and many of the women are kidnapped and sold into prostitution.

Musahar means “rat eaters,” a reference to this group’s traditional occupation of rat catchers. Although this population has indeed caught and eaten rats in the past, some individuals are beginning to go into nearby villages to work as agricultural laborers and day laborers. Regardless, they are well-known in the community as untouchables and therefore treated horribly by all other levels of society. Most of the families are victims of forced labor, and many of the women are kidnapped and sold into prostitution.

Musahars are so isolated that there have been very few programs targeting them in the past, and none led by Musahars themselves. Programs that did take place were limited in scope by capacity and resources, resulting in a siloed approach instead of addressing the multiple challenges facing the community, including deeply entrenched social, political, and gender-based discrimination. It is clear from Street Child’s experience that the success of any intervention for this population is twofold: 1. driving behavioral and attitudinal change, and 2. reducing the discrimination and marginalization constraining the Musahar women’s social and economic advancement. This must run alongside raising awareness of the rights of women and supporting them to raise their voice and claim those rights.

Source Materials

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/inpictures/2014/04/pictures-rat-eaters-india-201443081544438226.html

https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/17711/NP

https://idsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Nepal-UPR-2015-Dalit-Coalition-and-IDSN-report.pdf

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/np.html

https://www.internations.org/go/moving-to-nepal/living

https://www.everyculture.com/Ma-Ni/Nepal.html