— Aïssatou Diallo, Guinea

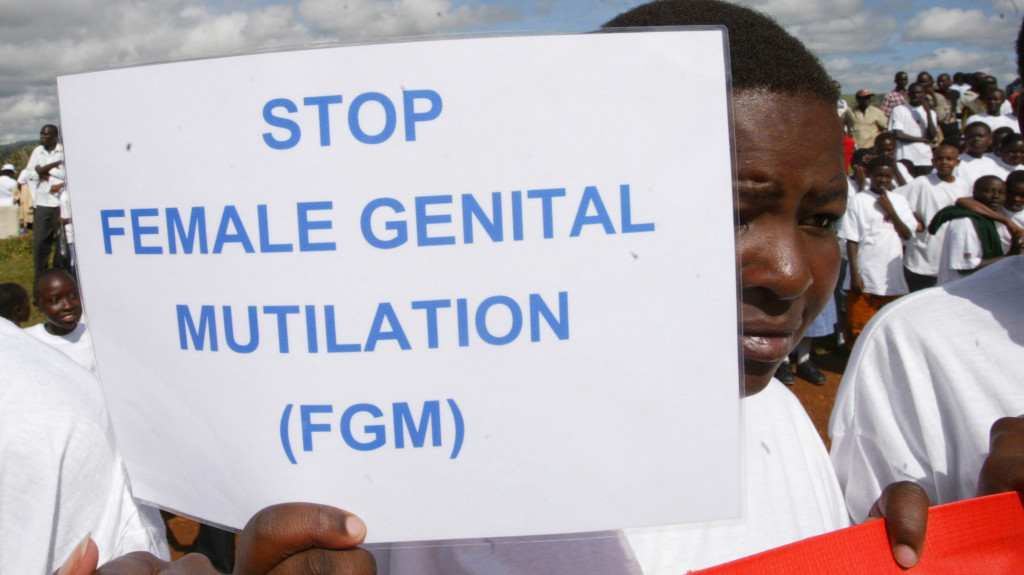

Theme: Ending “The Cut” – Stopping Female Genital Mutilation

Girls in the developing world have little or no control over their lives. In cultures in which it is practiced, female genital mutilation (FGM) is perhaps the most devastating manifestation of the way in which that lack of control extends to their own bodily integrity. Female genital mutilation (also known as female genital cutting or female circumcision) is a ritual procedure in which all or part of a girl’s external genitalia are removed without anesthesia. Ethnic groups in 27 sub-Saharan countries and northeast Africa practice FGM. It is also practiced in Yemen, south Jordan, and Kurdish Iraq, and within immigrant communities around the world. In February 2013, the World Health Organization reported that about 140 million girls and women worldwide have been subjected to the procedure, and that in Africa, an estimated three million girls are at risk annually.

Many African countries have banned the practice—Benin, Ivory Coast, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Niger, Nigeria, Central African Republic, Senegal, Chad, Tanzania, Togo and Uganda. However, in many, if not most of those countries, the tradition continues. In Kenya, the Children’s Act of 2001 was supposed to end the practice, but it was not strong legislation. The much stronger Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act passed in 2010, but it did not end the practice.

In many cultures, the purpose is to make a girl “clean” and therefore marriageable. (A local Ethiopian expression for FGM is “removing the dirt”.) FGM is usually carried out on young girls between infancy and age 15. Timing varies according to local custom. Frequently, a girl is cut around the time she reaches puberty, with the aim of marrying her off shortly thereafter. A unifying principle in most, if not all, cultures practicing FGM is the requirement that a girl be a virgin until she is married, and parents may hasten to have the procedure done for fear their daughter may not remain chaste once she has reached puberty. In some cultures, the family’s “honor” is contingent upon their daughter’s chastity. In cultures where a bride-price is required – the groom or his family pays for the bride in money or (like the Maasai), in cattle – a virgin commands a much better price.

FGM, combined with early marriage, almost invariably signals the end of a girl’s education and the continuation of a culture of disempowerment for her and her future family. It takes education for women to break the cycle of poverty, and without it, her children are far less likely to thrive and her daughters are also likely to be cut and married early.

This month, Dining for Women is supporting the Kakenya Center for Excellence, which works through education to motivate young girls to break the cycle of destructive cultural practices among the Maasai in Kenya, such as female genital mutilation and forced/early marriage. The founder of the Center is Kakenya Ntaiya, a Maasai woman. As a girl, she agreed to be subjected to FGM if her father would allow her to go to high school. She later negotiated with the Enoosaen village elders to go to college in the United States, promising to use her education to benefit the community. The entire village collected money to pay for her journey. She eventually earned her Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh and returned to the village to found the Center, which seeks to empower and motivate young girls through education to become agents of change.

Types of Female Genital Mutilation:

According to the World Health Organization’s Fact Sheet (updated 2013), there are four major types of FGM:

- Type 1: Clitoridectomy: partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitalia), or in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris).

- Type 2: Excision: partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without the excision of the labia majora. (The labia are the “lips” that surround the vagina.)

- Type 3: Infibulation: narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the inner or outer labia, with or without the removal of the clitoris.

- Type 4: Other: all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

— Tadeletch Shanko, Ethiopian woman who performed FGM on village girls for 15 years

Physical Consequences of Female Genital Mutilation:

While there are absolutely no health benefits to FGM, there are profound consequences, both during the process and throughout life. First of all, the cutting is usually done with ritual knives, used razor blades, can lids, broken glass and anything else sharp enough to sever tissue. These instruments are not sterilized, and so girls can be exposed to HIV, Hepatitis B, and other blood borne diseases. The cutting is done without anesthetic, so the girl must be held down while the cutting is done. The World Health Organization’s Fact Sheet on FGM states the following consequences:

Immediate complications: Severe pain, shock, hemorrhage, tetanus or sepsis (bacterial infection), urine retention, open sores in the genital areas, and injury to nearby genital tissue.

Long-term consequences: Risks increase with the increasing severity of the procedure

- Recurrent bladder and urinary tract infections

- Cysts, abscesses and genital ulcers

- Chronic pelvic infections can cause chronic back and pelvic pain

- Difficulty passing urine and menstrual fluid

- Excessive scar tissue

- Infertility

- Increased risk of childbirth complications, including obstetric fistula (Complications during pregnancy and childbirth, many due to FGM, are the leading cause of death among 15-19 year-old girls in Kenya)

- Newborn deaths, during and immediately after birth: 15 percent higher for Type 1, 32 percent higher for Type 2, and 55 percent higher for Type 3 In Africa, an additional 10 to 20 babies die per 1,000 deliveries as a result of FGM. (Statistics are for hospital birth. Likely to be much higher for home births.)

- Need for later surgeries

The “need for later surgeries” applies to the Type 3 FGM, infibulation. The narrowing of the vaginal opening is usually accomplished by sewing the cut flesh from the labia together, leaving a small hole through which to urinate and menstruate. The young girl’s legs are bound together for days, so the tissue grows together. This means that the girl or woman must be cut open on her wedding night or opened by slow tearing over the course of many days. Sometimes, women are re-infibulated after giving birth. Repeated openings and closings bear the same risks as the original procedure. Infibulation is slowly being replaced with less destructive forms of FGM, but across all countries where FGM is practiced, one in five women has undergone this most severe form.

It should be noted that the clitoris is the most sexually sensitive female organ, and its removal may compromise, or eliminate, a woman’s ability to experience sexual pleasure. (Clitoredectomies were performed on women in the Victorian era in the U.S. and Europe for masturbation, hysteria, epilepsy, mania and other supposed “abnormalities”.)

Psychological Consequences

The devastating psychological consequences, however, are just starting to receive the attention they deserve. Girls and women have serious long-term effects. A study reported in The American Journal of Psychiatry compared 23 Senegalese women in Dakar who had undergone FGM between the ages of 5 and 14—all without anesthesia, with 24 uncircumcised Senegalese women. All were between the ages of 15 and 40 years, and with an average length of education of 11.5 years.

The findings

- Almost 80 percent of the circumcised women met criteria for affective or anxiety disorders, with 30.4 percent showing high prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Among the uncircumcised women, only one met the diagnostic criteria for affective disorder.

- More than 90 percent of the women described feelings of “intense fear, helplessness, horror, and severe pain” and over 80 percent were said to be “still suffering from intrusive re-experiences of their circumcision”. For 78 percent of the subjects, FGM was performed unexpectedly and without any preliminary explanation

A similar study of Kurdish girls in Northern Iraq found that girls who had been cut had significantly higher prevalence of PTSD (44.3 percent) and depression (33.6 percent) than uncircumcised girls.

Reasons for the Practice:

The origins of FGM are lost in time, but it probably originated in Africa. FGM has been traced back as far as ancient Egypt’s Middle Kingdom. A practice of such long standing is deeply entrenched, and only in modern times have there been strong efforts to end it. It is so deeply entrenched that some cultures do not consider an uncut adult female a woman. She will be stigmatized, and unmarriageable.

Many believe that their religion requires it. It is more common among Muslim communities. (An organization working with considerable success to end FGM in West Africa, where many communities are Muslim, is Tostan. A major component of their process is to engage the assistance of the local Imams to teach the community that there is no requirement for FGM in Islam, and that there is no mention of it in the Koran.) A July 2013 UNICEF study, Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change, reported that over 50 percent of girls and women in four out of fourteen countries in Africa regarded FGM as a religious requirement, whereas men only agreed with that percentage in two countries.

— Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu

FGM is a cultural, rather than a religious, practice. For example, in Ethiopia, an estimated 75 percent of women have undergone the procedure. Yet the population is 63 percent Christian and 34 percent Muslim. Even the tiny population of the Beta Israel Jews practice FGM.

While the loss of the ability, or diminished capacity, to experience sexual pleasure is a loss to the individual, that is only one of the main objectives. The intent is to control women by controlling their capacity for pleasure, so they are less likely to be interested in premarital sex. When chastity is a central requirement in a culture, it is a matter of ensuring conformity. In conflict situations and refugee camps, parent may hasten to cut their daughters, believing it will make it more difficult for a rapist—but it will only make rape more horrific for the girl. A husband may prefer that his wife be circumcised in the belief that it will prevent adultery.

How FGM is Viewed by Men and Women

Interestingly enough, women are more resistant to ending the practice of FGM than men, and in some cases, by a significant margin. In the UNICEF study on FGM cited above, girls and women who have been cut are more likely to favor continuing the practice – but a sizeable percentage (a majority in many countries) – want it to end. Girls with no education are substantially more likely to support the continuation of FGM. Some of the data may be skewed by the variations on what women know about negative consequences of FGM, and perhaps on how much they are influenced by the attitudes of the larger society.

In most countries, the majority of boys and men think that FGM should end, which stands in contradiction to the assumption that FGM is an example of patriarchal control. For both men and women, support for FGM is in inverse proportion to level of education.

A 2013 Inter Press Service article in All Africa reported a growing interest on the part of men and boys in Kenya for ending the practice. Their reasons vary, including avoiding expensive birth difficulties, a more mutually satisfying sex life, and/or an interest in daughters having a good education. More men are announcing their preference to marry uncut girls. A local council in Kenya’s Rift Valley, where the most extreme form of FGM is practiced, has announced that is it okay to marry a girl who is not circumcised. That kind of “official” approval will hasten the end of FGM.

Female Genital Mutilation as a Human Rights Issue:

Whether or not FGM is legal, it definitely falls within the definition of a violation of human rights, as follows.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) Articles 3 and 5

- UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (1993) Article 2, Section a

- Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (also known as the Maputo Protocol) (2003) Article 2, 3, 4, 5

(The following countries have neither signed nor ratified the protocol: Botswana, Central African Republic, Egypt, Eritrea, Sao Tome and Principe, South Sudan, Sudan, and Tunisia.)

The Medicalization of FGM

The traditional practice of FGM has focused negative attention on many cultures, particularly in Africa, and especially as people are becoming aware of the harmful consequences. As a result, many families that are reluctant to abandon the tradition are turning to doctors to perform the same procedures under anesthetic and with sterile instruments. The reasoning is that FGM is not the problem, but the way it is being done is harmful. According to the World Health Organization, existing data (where available) show that more than 18 percent of all girls and women subjected to FGM had the procedure performed by a health care provider – which WHO defines as “physicians and assistant physicians, clinical officers, nurses, midwives, trained birth attendants, and other personnel who provide health care”. This means, of course, varying levels of medical knowledge and skill.

The World Health Assembly in 2008 adopted a resolution on the elimination of FGM, with all member states agreeing to work toward that goal, and agreeing that FGM is a violation of human rights. Some believe that medicalization is the first step toward ending the practice. But the involvement of health care providers lends a sense of legitimacy to FGM, with the impression that it is not harmful.

Health care providers who perform FGM have a wide variety of reasons: Many are from FGM-practicing communities, and it is part of their culture. Others think it is their duty to support a culturally motivated request, and yet others see it as harm reduction—it will be done anyway, and the danger is much greater with traditional practices. And, of course, some are primarily interested in financial gain. To meet the demand, some doctors are holding lucrative FGM clinics during school holidays and performing dozens of surgeries per day.

The custom of FGM in most countries is deeply entrenched, and it appears that the quickest way to stop—or at least inhibit—the medicalization of FGM is to make the surgery a criminal offense.

Criminalization/Outlawing FGM

The UN passed a resolution calling for a global ban on FGM in December 2010. More and more countries are passing strict laws against FGM. There is definitely pushback from tribes and ethnic groups claiming exemption in the name of culture. Several responses are happening at once: Some groups are continuing the practice, but going “underground”—performing the procedures in secret. As girls are becoming educated in school about the procedure, some groups have responded by cutting girls at younger ages. There are more and more reports of adolescent girls running away from home to avoid being cut. And in many cases, the information that FGM is illegal may not yet have made it to all the villages that would be affected. Doctors, of course, are performing the service off the record. The push in several countries is to ensure there are criminal penalties for parents, village cutters, and doctors. Kenya’s new law prohibiting FGM includes stiff penalties for anyone participating in the practice, including medical personnel.

Diaspora – FGM among Immigrants and Refugees

Millions of people have left homelands where FGM is practiced to live in developed countries in North America, Europe, or Australia/New Zealand. They may have emigrated for better opportunities or fled wars and insurgencies. Understandably, immigrants tend to cluster in communities in their new countries. People bring with them their culture, which includes such harmful practices as FGM and forced marriage (and even honor killings). Most countries in the developed world have laws that protect citizens and residents from torture or other bodily assaults. Many, but not all, have laws that specifically ban FGM in all its forms, with serious penalties for performing such procedures and often for taking daughters abroad for that purpose—called “vacation cutting”. Also, a significant number of countries offer asylum to anyone fleeing a country to avoid the procedure. But enforcement has been spotty.

United States: The U.S. has banned FGM since 1996, but until recently, vacation cutting was banned in only Florida, Georgia, and Nevada. Congress passed the “Transport for Female Genital Mutilation” law in December 2012 as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act. It imposes a fine and a prison sentence of up to five years on those found guilty of sending or taking girls under the age of 18 out of the country for the purpose of FGM.

United Kingdom: Although FGM has been outlawed since 1985 and carries a maximum penalty of 14 years in prison, there has never been a single prosecution. British medical groups recently delivered a report to Parliament that claims as many as 66,000 cases of FGM in Britain. In addition, more than 24,000 girls are at risk. The group recommends strong new measures. A 2010 article in The Guardian asserted that between 500 and 2,000 girls would be cut during an upcoming holiday, when families would go to the home country. In an effort to save money, sometimes families will pool money and pay for a cutter to come from the home country to do “cutting parties”.

France: Home of up to 30,000 women who have been cut, and thousands of girls at risk, France has been active and very successful in curbing FGM—both in prevention and prosecution, according to the Thompson Reuters Foundation. Although there is no specific law banning FGM per se, mutilation or abuse of minors is a crime under the Penal Code. Doctors are encouraged to do genital checks on babies and young children, which have been valuable in successful prosecutions. Some mothers obtain a doctor’s certificate stating that the child has not been cut before they visit their home country, which serves as a curb to family members who want the child cut while on holiday. In 1999, an FGM practitioner in France was sentenced to eight years in prison.

Europe as a whole: According to Amnesty International’s End FGM campaign in Europe, “medicalisation of FGM in any form has been rejected by the European Parliament, WHO and professional organisations such as the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.” However, the Council of Europe issued a statement on FGM that rebukes Europe as a whole for failing to protect women and girls, and for having no specific protection through refugee status for women and girls fleeing the prospect of FGM.

Canada: Canada’s Criminal Code includes a section on “Excision” under “Aggravated assault” that specifically describes FGM. However, there seems to be no specific provisions in the law banning parents from having their child cut outside the country. More attention is being paid by the medical profession to methods of treating women and girls who have been subjected to FGM.

Australia: All territories ban FGM and criminalize the removal of any person from the country in order to have the procedure done.

The best news is that, almost across the board in countries where FGM is practiced, the incidence has been going down. More communities are ending the practice, and more and more traditional cutters are renouncing their role and expressing regret for the harm they have unwittingly done. With the power that men and boys have in traditional societies, their increasing support for ending the practice is critical. For the girls whose future relies on education, health, and involvement in the world, the end can’t come too soon.

— Geeta Rao Gupta, UNICEF Deputy Executive Director

Donna Shaver, Author

Source Materials

- Anderson, Lisa. “New US law criminalises sending girls abroad for FGM”. Thomson Reuters Foundation. January 31, 2013. http://www.trust.org/item/?map=new-us-law-criminalises-sending-girls-abroad-for-fgm

- Batha, Emma. “Sister’s death spurs Ethiopian activist to fight female genital cutting“ Thomson Reuters Foundation. June 28 2013. http://www.trust.org/item/20130628133635-9enq0/

- Behrendt, Alice and Steffen Moritz. “Posttraumatic stress disorder and memory problems after female genital mutilation”. The American Journal of Psychiatry. V. 162 n. 5, pp 1000-1002. http://journals.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=177537

- “Country profile: FGM in Kenya” 28 Too Many. May 2013. http://www.28toomany.org/countries/kenya/

- “Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence-Thematic Factsheet: Female Genital Mutilation”. Council of Europe. (no date) http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/standardsetting/convention-violence/brochures_en.asp

- Dugger, Celia W. “Report finds gradual fall in female genital cutting in Africa.” The New York Times. July 22, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/23/health/report-finds-gradual-fall-in-female-genital-cutting-in-africa.html

- Fahmy, Gabrielle. “Female genital mutilation a ‘huge problem’ in the U.K”. CBC News. December 4, 2013. http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/female-genital-mutilation-a-huge-problem-in-u-k-1.2439423

- “Female circumcision act in force.” BBC News, March 3, 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/3528095.stm

- “Female genital mutilation” Fact sheet No 241. Media Centre. World Health Organization. February 2013. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/

- “Female Genital Mutilation”: Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Female_genital_mutilation – cite_note-97

- “Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change.” UNICEF. http://www.unicef.org/protection/57929_58002.html

- Gathigah, Miriam. “Kenya: men turning the tide against FGM”. AllAfrica. February 6, 2013. http://allafrica.com/stories/201302070542.html

- “Global strategy to stop health-care providers from performing female genital mutilation”. World Health Organization. 2010. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/fgm/rhr_10_9/en/index.html

- “Health complications of female genital mutilaton.” World Health Organization. (no date) http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/health_consequences_fgm/en/

- Laws of the world on female genital mutilation.” Harvard School of Public Health. (as of February 2, 2010) http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/population/fgm/fgm.htm

- “Legislative reform in Kenya to speed up abandonment of FGM/C: Strong government policy to support new law. UNFPA. (No date.) http://www.unfpa.org/gender/docs/fgmc_kit/Kenya-1.pdf

- “Kenya: Protect girls by enforcing FGM and child marriage laws.” Equality Now. Action Number 52.1. October 10, 2013. http://www.equalitynow.org/take_action/fgm_action521

- Kizilhan, Jan Ilhan. “Impact of psychological disorders after female genital mutilation among Kurdish girls in Northern Iraq”. European Journal of Psychiatry. Vol. 25, No. 2), June 2011. http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S0213-61632011000200004&script=sci_arttext&tlng=es

- McVeigh, Tracy and Tara Sutton. “British girls undergo horror of genital mutilation despite tough laws”. The Guardian/The Observer. July 24, 2010. (Includes a video interview with a girl who was cut in Britain during a school holiday.) http://www.theguardian.com/society/2010/jul/25/female-circumcision-children-british-law

- “New study shows female genital mutilation exposes women and babies to significant risk at childbirth”. World Health Organization. June 2, 2006. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2006/pr30/en/

- Review of Australia’s Female Genital Mutilation Legal Framework – Final Report. Australian Government – Attorney-General’s Department. 24 May 2013. http://www.ag.gov.au/Publications/Pages/ReviewofAustraliasFemaleGenitalMutilationlegalframework-FinalReportPublicationandforms.aspx

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18065832

- Rowling, Megan. “France reduces genital cutting with prevention, prosecutions – lawyer”. Thomson Reuters Foundation. September 27, 2012. http://www.trust.org/item/?map=france-reduces-genital-cutting-with-prevention-prosecutions-lawyer/

- Tulloch, Teleta. “In Ethiopia, African women parliamentarians condemn female genital mutilation.” UNICEF. September 14, 2009. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/ethiopia_51122.html

- “UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on female mutilation/cutting: Accelerating change 2008-2010 – Kenya.” April, 2013. http://www.unicef.org/evaluation/files/fgmcc_kenya_final_ac.pdf

- “OIC chief calls for abolition of female genital mutilation.” Trustlaw. Thomson Reuters Foundation. December 4, 2012. http://www.trust.org/item/20121204114600-k6dat/?source=search

- “Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa.” Article 5 “The elimination of harmful practices. African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. July 2003. http://www.achpr.org/instruments/women-protocol/ – 3

- “OIC chief calls for abolition of female genital mutilation.” Trustlaw. Thomson Reuters Foundation. December 4, 2012. http://www.trust.org/item/20121204114600-k6dat/?source=search