Mission

Burma Humanitarian Mission (BHM) supports community-based, predominantly women-led backpack medics who administer village healthcare services and grassroots education programs to the displaced people of Myanmar (formerly Burma).

Life Challenges of the Women Served

Since the end of World War II, the ethnic minority people of Myanmar have struggled to maintain their freedom, culture and identity. This population – the Karen, Kachin, Karenni, Pa’laung, Chin, Shan, Mon and others – were promised autonomy and independence from the Burmans, the country’s ethnic majority and rulers of the state. Instead, the military has oppressed, isolated, and violently attacked these minorities for 60+ years, seizing power and launching strikes to isolate and negate the minority people’s quest for independence. Human Rights organizations have documented land confiscation, extrajudicial killings, forced labor, and sexual violence. The Myanmar army uses rape as a weapon of war to intimidate women and communities.

By 2000, more than 500,000 people had fled their homes for the sanctuary of internally displaced person (IDP) camps in Myanmar’s jungles while another 250,000 lived in refugee camps in Thailand, where they are at risk for arrest, detention and return at the whim of Thai authorities. In eastern and northern Myanmar, ethnic minority women and children live in isolated villages or IDP camps, where they endure illness, disease and malnutrition. Their families are primarily farmers with average annual incomes of $200. These families have no access to medical care for injuries caused by the violence or illnesses endemic to living in remote areas. In addition, their diseases are worsened by food scarcity and malnutrition, creating far greater mortality and morbidity rates.

By 2000, more than 500,000 people had fled their homes for the sanctuary of internally displaced person (IDP) camps in Myanmar’s jungles while another 250,000 lived in refugee camps in Thailand, where they are at risk for arrest, detention and return at the whim of Thai authorities. In eastern and northern Myanmar, ethnic minority women and children live in isolated villages or IDP camps, where they endure illness, disease and malnutrition. Their families are primarily farmers with average annual incomes of $200. These families have no access to medical care for injuries caused by the violence or illnesses endemic to living in remote areas. In addition, their diseases are worsened by food scarcity and malnutrition, creating far greater mortality and morbidity rates.

The resulting health crisis is horrific. Without care, 135 infants die in the first 28 days for each 1,000 births while the maternal mortality rate is 7.2 per 1,000 births. (The U.S. infant mortality rate is 5.8/1,000 and MMR is 0.43/1,000.) The mortality rates for this area are abhorrently worse than in Myanmar as a whole, and significantly worse than neighboring Thailand and world standards in general.

The Project

Burma Humanitarian Mission (BHM) works in partnership with the Backpack Health Worker Team (BPHWT) to recruit and train backpack medics who serve Myanmar’s displaced and isolated ethnic communities in conflict zones. Each year, BHM’s primary goal is to support 12 predominantly women-led backpack medic teams with medicine and supplies to reduce maternal and infant/child mortality rates, disease and malnutrition. BHM supports four teams in these northern conflict zones and ten in the eastern conflict zones. In addition to BPHWT, BHM works closely with the well-respected international Mae Tao Clinic, which provides instructors, formularies, and assistance with the medic training syllabus. To date, 76 percent of all medics have been women. The typical team consists of:

5 medics (2-3 senior medics paired with 2-3 junior medics)

5 medics (2-3 senior medics paired with 2-3 junior medics)- 5 Village Health Volunteers (VHV)

- 5 to 10 Traditional Birth Assistants (TBA)

The backpack teams are outfitted with an array of basic medicine: Penicillin, Amoxicillin, various anti-malarial treatments and more. The teams also rely upon more than 3,000 individual medical supply items, such as bandages, gauges, syringes, stethoscopes and thermometers. The teams provide three core program capabilities:

- Medical Care Program (MCP) – treating injuries, illnesses and diseases

- Mother-Child Health Program (MCHP) – providing prenatal, childbirth and post-delivery support to women and their newborns,

- Community Health Education and Prevention Program (CHEPP) – providing preventative care by promoting sanitary programs (clean water and latrines), malaria prevention, family planning support, nutrition and school age supplements and similar efforts aimed at reducing the likelihood of disease and illness.

Through this project, 180 women will have the opportunity to serve as backpack medics – breaking gender and cultural stereotypes to be leaders in their villages and communities, developing critical skills, and reducing poverty and suffering. In addition, the predominantly women-led backpack medic teams will aim to dramatically reduce infant and maternal mortality rates, saving nearly 50 babies and 3 mothers every year. The goal is for infant mortality rates to drop from 135/1,000 to less than 2/1,000 births and for maternal mortality rates to drop from 7.2/1,000 to 1/1,000 births. In addition, the DFW grant will allow 1,200+ women and girls to survive who otherwise would have died. In total, almost 27,000 women and girls will have access to medical care, maternal/child health care, and benefit from shared community health practices – and 75,000 will be reached indirectly. The medics will treat every individual at no charge, in their native language and consistent with their cultural norms.

Outcomes are evaluated twice each year by reviewing the medic teams’ log books that document the number of patients, symptoms, diagnosis, treatments and results. These results are compared to the goals, objective and historical trends. Based on historic rates (2002-03), the DFW grant will support the following annual outcomes:

- Reduced Infant Mortality rate:

- Historic rate: 135 deaths/1,000 births

- 2017 goal: 2 deaths/1,000 births

- Reduced Maternal Mortality rate:

- Historic rate: 7.2/1,000 births

- 2017 goal: 1/1,000 births

- Reduced Malaria Rate

- Historic rate: 11.8 percent of population suffered from malaria

- 2017 goal: 0.5 percent – 2,950 fewer women and girls suffering from malaria

- Reduced Pneumonia Rate

- Historic rate: 2.83 percent of population suffered from pneumonia

- 2017 goal: 2 percent – 234 fewer women and girls suffering from pneumonia

- Reduced Dysentery Rate

- Historic Rate: 2.8 percent of population suffered from dysentery

- 2017 goal: 1.2 percent – 418 fewer women and girls suffering from dysentery

The medics develop a semi-annual medicine and supply list, which BHM funds, procures and delivers. (Each team requires 60,000 doses of medicine each year.) Each team travels among nine to twelve villages and/or IDP camps each month, providing care and education. The teams are supported by five village health volunteers and up to ten trained traditional birth assistants who remain in their village/IDP or support the medics at one to two nearby locations. On a typical day, the medics will treat 5 – 20 individuals. For childbirth, the medics will travel to the mother’s location when necessary.

Volunteers are evaluated based on recommendations of village and community leaders plus the woman’s demonstrated desire to serve. Typically, there are 50 to 60 female medic recruits each year. The staff includes seasoned medics who have taught the curriculum for 5 to 20 years after having served as field medics themselves. Training includes first aid, basic physiology and anatomy, basic formularies and drug administration, record keeping, community health practices, rape and sexual assault counseling and family planning education. The backpack medics reduce disease and death among women and children by providing direct medical care, responsive maternal/newborn care and preventive care measures. The teams are also trained to provide community education on measures against sexual violence as well as to provide support to survivors of sexual violence. The backpack teams are the only source of support for women and girls in the conflict zones.

Volunteers are evaluated based on recommendations of village and community leaders plus the woman’s demonstrated desire to serve. Typically, there are 50 to 60 female medic recruits each year. The staff includes seasoned medics who have taught the curriculum for 5 to 20 years after having served as field medics themselves. Training includes first aid, basic physiology and anatomy, basic formularies and drug administration, record keeping, community health practices, rape and sexual assault counseling and family planning education. The backpack medics reduce disease and death among women and children by providing direct medical care, responsive maternal/newborn care and preventive care measures. The teams are also trained to provide community education on measures against sexual violence as well as to provide support to survivors of sexual violence. The backpack teams are the only source of support for women and girls in the conflict zones.

Serving with predominantly women-led backpack medics is an exemplary means for ethnic-minority women to realize a positive contributory and leadership role in their villages and communities. Given their societies are mostly agrarian, women have often been secondary laborers to men. However, serving with predominantly women-led backpack medics – in the field or in leadership positions – women break the mold. As field medics, women provide the leadership to raise their villages and communities out of poverty and malnutrition-fueled disease, mortality and morbidity cycles. As such, women medics serve their communities and are also role models and leaders. The DFW grant will allow BHM to continue, extend and improve the quantity of these backpack medic teams to new areas – providing MCP, MCHP, and CHEPP to 26,644 new women and young girls every year.

Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- Why are backpack medics a more effective solution to healthcare than conventional clinics?

- How will young daughters benefit from seeing their mothers as backpack medics?

- How do you think having backpack medics as role models and community leaders will impact future generations?

How the Grant Will be Used

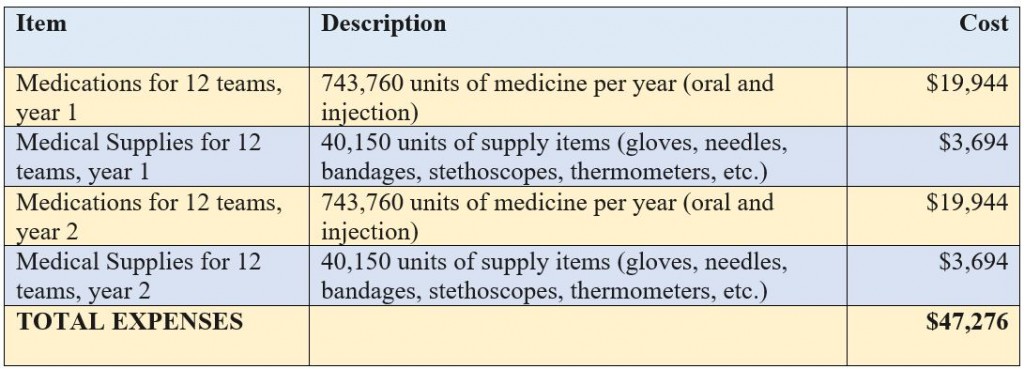

DFW’s grant of $47,276 over two years will be used to fund 12 backpack medic teams. Each team receives 61,980 doses of medicine per year and 3,346 supply items. The grant supports 26,644 women and girls per year (an average of 89 cents per person) and allows 11,832 women and girls per year to receive treatment ($1.99 per person).

| Year 1- Direct Impact: 26,644 | Indirect Impact: 75,000 |

| Year 2- Direct Impact: 26,644 | Indirect Impact: 75,000 |

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love this project because it enhances and saves the lives of women and girls who have little or no access to health care, and who are at risk for oppression, isolation, and violent attacks.

Evidence of Success

The BHM-BPHWT partnership has changed the lives of women and girls in Myanmar. BHM has been awarded 4 stars out of 4 by Great Non-Profits, and is also a Guidestar Gold Member.

In 2016 alone, BHM supported 14 backpack teams, with impressive results:

- Cared for 30,481 people

- Delivered 841,088 doses of medicine

- Treated 13,435 patients – 7,389 women and girl patients

- Delivered 436 babies

- Reduced IMR from 135/1,000 to 1.6/1,000

- Reduced MMR from 7.2/1,000 to 1.1/1,000

- Reduced the incidence of malaria from 3.7/100 to 0.41/1,000 people

- Each team saved an average of 48 people by preventing and treating diseases.

Voices of the Girls

“Without backpack medics, I do not know what we would do. My mother became sick with malaria. Backpack medics came to my village and gave her medicine. She lived. I would have been lost without my mother.”

“Without backpack medics, I do not know what we would do. My mother became sick with malaria. Backpack medics came to my village and gave her medicine. She lived. I would have been lost without my mother.”

Karen mother and child

“It is very hard to help women who are pregnant. When something goes wrong, it really saddens me. Too often, women wait too long to get help. I’m always glad when women want our help early and during their pregnancy. Mother and infant deaths have been reduced because of this.”

Naw Aye Aye Pwint, Mother-Child Health Supervisor, Win Yee BPHWT Field Area

“It’s very good when a baby arrives without any problems. When things go wrong, we have to work very hard because the fighting near us means we cannot get help. It’s not always easy.”

Lway Katae Nyime, Backpack Medic in Kachin State

“I am a Pa’laung backpack medic in Shan State. Since 2011, the Burma army started fighting my people again. We have no hospitals or doctors to help us. I treated this young girl who had Pf malaria. I was happy I could help her and she lived.”

Lway Poe Khoung

About the Organization

BHM was founded in 1999 by a group of friends who visited the Thai-Myanmar border and met Karen leaders who needed help starting a backpack medic program to care for their people. The group raised funds for medicine and supplies and traveled with a team the next year, seeing firsthand how great the need was and how a few dollars secured vital medicine that saved lives. They were inspired by the positive role that women played in their villages and ethnic communities as a whole. They also recognized that assisting women in Myanmar’s conflict zones would not just alleviate suffering and promote gender equality, but that these women were the primary catalyst for positive change – to rise and lead their communities away from poverty and suffering. BHM was granted 501c3 status in 2009.

Today, BHM is a small, streamlined organization with a board of five people who support, promote and empower grassroots initiatives that are led by partner organizations such as BPHWT. Together, these organizations serve over 50,000 villagers with medical care and support education efforts that touch over 500,000 lives annually. BHM also provides educational opportunities for youth by supporting a secondary school along the Thai-Myanmar border as well as a mobile primary school in Myanmar’s largest city, Rangoon.

Today, BHM is a small, streamlined organization with a board of five people who support, promote and empower grassroots initiatives that are led by partner organizations such as BPHWT. Together, these organizations serve over 50,000 villagers with medical care and support education efforts that touch over 500,000 lives annually. BHM also provides educational opportunities for youth by supporting a secondary school along the Thai-Myanmar border as well as a mobile primary school in Myanmar’s largest city, Rangoon.

BHM’s methodology is proven and repeatable. The organization works closely with BPHWT at every level to tailor the delivery of support required. Historical data is used to recognize the baseline mortality and morbidity rates before backpack medics were available throughout Myanmar’s conflict zones. Every six months the team leads meet in Mae Sot, Thailand, for an operational and strategy review in which they review the log books of every patient encounter. The team reviews all treatments from a quality control perspective (correct diagnosis, treatment, improvements needed, etc.). The results are collated into semi-annual and annual reports, with trend analyses and outcomes noted.

BMH’s approach is also extremely cost efficient. For instance, Americares provided $40 million of medical support to 40,000 survivors of Cyclone Nargis in 2008, an average of $1,000 per person for one year. BHM spends an average of $1.10 per person supported.

Where They Work

Myanmar is a country of 59 million people in southeastern Asia, bordering Bangladesh, China, India, Laos and Thailand. It is approximately the size of Texas. It is characterized by tropical climate and lowlands in the central area ringed by steep, rugged highlands. Myanmar is rich in jade, gems, oil, natural gas and other mineral resources. The income gap is among the widest in the world, since the majority of the economy is controlled by supporters of the former military government. BHM’s primary service area is in Myanmar’s conflict zones in eastern and northern Myanmar: Karen, Karenni, Shan, Kachin and Mon States.

Myanmar is a country of 59 million people in southeastern Asia, bordering Bangladesh, China, India, Laos and Thailand. It is approximately the size of Texas. It is characterized by tropical climate and lowlands in the central area ringed by steep, rugged highlands. Myanmar is rich in jade, gems, oil, natural gas and other mineral resources. The income gap is among the widest in the world, since the majority of the economy is controlled by supporters of the former military government. BHM’s primary service area is in Myanmar’s conflict zones in eastern and northern Myanmar: Karen, Karenni, Shan, Kachin and Mon States.

Myanmar’s history includes a series of city-states and dynasties, falling to Mongol invasions that resulted in several warring states. In the 16th Century it was the largest empire in the history of mainland Southeast Asia. Myanmar became a British colony in the 19th Century after three wars. It was granted independence in 1948, initially as a democratic nation and then, following a coup in 1962, a military dictatorship. For most of these years, it has seen profound ethnic strife, culminating in one of the world’s longest-running ongoing civil wars. During this time, there have been consistent and systematic human rights violations.

The military junta was voted out in 2010, replaced by a civilian government. This, plus the release of political prisoners, has improved the country’s human rights record and foreign relations. However, what is difficult for many Americans to comprehend is that the Myanmar Army is independent from the elected, national government. Hence, the ascension of Noble Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party to the majority in Myanmar’s Parliament has no effect on the Myanmar Army’s military operations against the ethnic groups.

A closer look at health care in conflict zones

People don’t “plan” when and where they are going to get sick. As a human right – and a necessity – people require medical attention in conflict zones just as  they do in peaceful areas. In addition to ongoing healthcare, it is necessary to stop the spread of disease and to treat injuries sustained in war. In fact, health issues are often exacerbated in conflict areas because people are often living in close quarters and focused on survival instead of healthcare.

they do in peaceful areas. In addition to ongoing healthcare, it is necessary to stop the spread of disease and to treat injuries sustained in war. In fact, health issues are often exacerbated in conflict areas because people are often living in close quarters and focused on survival instead of healthcare.

Numerous problems arise when trying to make healthcare accessible in conflict zones. To start, there is usually a lack of healthcare workers and medical supplies available, and delays in treatments and vaccinations. These issues are especially pronounced when air strikes are present and relief workers are unable to provide care due to safety concerns. Hospitals and clinics are often unable to operate or to accommodate the wounded and ill.

Often, humanitarian aid is the only way care can be made available, providing a stop-gap measure. The threat to these relief workers is very real: in 2013, 155 relief workers were killed, 168 injured and 132 kidnapped.

Source Materials

https://www.hcs.harvard.edu/hghr/online/securing-health-care-in-war-zones/

http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/human-capital-and-risk/healthcare-in-war-zones-10-things-to-know.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3176880/

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bm.html