Mission

The mission of The Center for Victims of Torture (CVT) is to heal the wounds of torture on individuals, their families, and their communities and to end torture worldwide.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

Women and girls living in Uganda face a number of complex challenges to their mental health status as a result of current and historic humanitarian emergencies. This situation has left families facing financial, social, psychological, and physical health symptoms. Uganda hosts nearly 1.5 million refugees fleeing from neighboring humanitarian emergencies, and it is also still recovering from nearly 20 years of conflict between the government and the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) – whose leaders stand accused and have been convicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) of widespread torture and human rights violations. Therefore, Uganda is striving to provide opportunities and basic social services to its citizens and refugees, but health and financial challenges continue to be barriers while accessing such services.

CVT is concerned with the mental health of refugee and local communities living within Uganda. The LRA conflict was particularly troublesome for women and children, as thousands of baby girls were kidnapped from their families, trafficked, and forced to be child soldiers, or used as sex slaves for men combatants. During captivity, many women contracted HIV and delivered children born of rape. Women returning home after capture feel immense shame and self-blame, are unable to access resources, have limited education, and experience trauma symptoms from growing up and living amidst violence. In addition, they may face rejection and blame from their families and communities. Together, these factors, compounded with witnessing murder, experiencing rape, and being tortured, have a profound impact on the mental health and well-being of women survivors and their families.

CVT is concerned with the mental health of refugee and local communities living within Uganda. The LRA conflict was particularly troublesome for women and children, as thousands of baby girls were kidnapped from their families, trafficked, and forced to be child soldiers, or used as sex slaves for men combatants. During captivity, many women contracted HIV and delivered children born of rape. Women returning home after capture feel immense shame and self-blame, are unable to access resources, have limited education, and experience trauma symptoms from growing up and living amidst violence. In addition, they may face rejection and blame from their families and communities. Together, these factors, compounded with witnessing murder, experiencing rape, and being tortured, have a profound impact on the mental health and well-being of women survivors and their families.

The LRA conflict resulted in the displacement of 2.8 million people, and much of the world has forgotten a large number of survivors still requiring care. Women survivors (70 percent of CVT clients) of the LRA conflict are different from other trauma survivors, as they were victims of violence and were forced to perpetuate it. Children were forced to kill their parents, men forced to rape their sisters, and children abducted and forced to be LRA soldiers. Among CVT clients, 87 percent were captured, detained, or held against their will, and 67 percent were victims of human trafficking. Thus, the trauma of torture is compounded by the guilt and stigma of having to participate in brutality. Despite some progress providing mental health resources, the passage of time and shift in global attention has meant that many other donors, and therefore many services, have disappeared from the region.

For decades, Uganda was affected by political instability and civil war, and international aid in response was aimed at supporting basic needs, livelihoods, psychosocial improvements, education, and medical services. Today, a significant number of women and children still require mental health services to recover from symptoms suffered during war. Specialized mental health services in the region are currently lacking, and the few NGOs offering support have limited staff working to address the need, and that staff is overwhelmed.

The impacts of previous and current humanitarian emergencies in Uganda are still severe in many regions where CVT operates, especially since a majority of women seeking services have never received mental health services. Women integrating into society after being held captive are considered by other community members as second class and rejected by the community. They often have little-to-no education, work experience, or social skills. They may have severe trauma symptoms (flashbacks, mind-body disassociation, emotional triggers) and utilize negative coping strategies (alcohol or drug abuse, social withdrawal). In addition, women must balance the cultural and religious norms after returning with children (born from sex trafficking or rape), no husband, and without the ability to own land.

The Project

The goal of the CVT Uganda program is two-fold, providing mental health services to torture and trauma survivors, as well as developing the capacity of mental health practitioners, particularly women and the broader community. CVT aims to improve the quality of life for women and help them pursue their own goals and create lasting change in their lives. The two objectives of this project are: 1. for direct services, to improve the mental health of torture and war trauma survivors through individual and group mental health counseling, and 2. for training, to strengthen the capacity of Ugandan mental health care providers to understand, identify, support, and treat survivors of torture and trauma.

Program beneficiaries include Ugandan women survivors of torture and trauma, and Ugandan and international organizations providing mental health services to Ugandan and refugee communities. Women often experience sexual and gender-based violence impacting physical and psychological symptoms such as shame, humiliation, and relationship difficulties. Therefore, it is not surprising that among CVT clients, 92 percent experience a medium-to-high severity of depression and PTSD at the start of services.

CVT offers mental health counseling provided by local counselors hired, trained, and supervised by CVT expert staff. The majority of counseling services are provided through group counseling with 10 – 12 participants, lasting three months including a two-session intake and an individual check-in and mid-group cycle. This group model follows Dr. Judith Herman’s stages of trauma recovery which includes initial focus on safety and stabilization, processing of traumatic memories and working through grief, and finally reconnection to self and community including restoring hope and dignity. Groups are formed according to age, gender, and similar trauma history. Individual treatment is available if necessary (such as for a woman who experienced sexual assault or attempted suicide). Session topics include safety and trust, mind-body awareness, sharing difficult memories, grief/loss, reconnection to self, community and the future.

CVT’s specialized mental health services support and empower women to live self-sufficient lives in the following ways: 1. through counseling, women improve their functioning significantly, allowing them to take steps to better care for themselves and their families; 2. women are referred for medical and livelihood services, thereby improving their health and financial stability; and 3. counseling gives women the support of other women to know they are not alone, to be integrated back into the community, and to learn how to assert their needs as an individual. By reclaiming their dignity (a core objective of the CVT group model), they develop the strength to claim a new identity for themselves beyond what is prescribed for them by the cultural norms — resulting in increased sense of empowerment. CVT also works with a livelihood partner to educate communities on Village Savings and Loan Association and Income Generation Activities, and many CVT clients reported they were committed to start income generation activities with personal savings instead of loans. CVT staff consistently see an increase in self-determination and an ability to access resources after participation in CVT services.

CVT’s specialized mental health services support and empower women to live self-sufficient lives in the following ways: 1. through counseling, women improve their functioning significantly, allowing them to take steps to better care for themselves and their families; 2. women are referred for medical and livelihood services, thereby improving their health and financial stability; and 3. counseling gives women the support of other women to know they are not alone, to be integrated back into the community, and to learn how to assert their needs as an individual. By reclaiming their dignity (a core objective of the CVT group model), they develop the strength to claim a new identity for themselves beyond what is prescribed for them by the cultural norms — resulting in increased sense of empowerment. CVT also works with a livelihood partner to educate communities on Village Savings and Loan Association and Income Generation Activities, and many CVT clients reported they were committed to start income generation activities with personal savings instead of loans. CVT staff consistently see an increase in self-determination and an ability to access resources after participation in CVT services.

For capacity building programming, CVT delivers programming to three different populations of providers: 1. internally hired CVT staff, 2. masters-level interns from Makerere University, and 3. local counselors from partner organizations, some of whom participate in a diploma program accredited by Makerere University.

The Diploma in Trauma Counseling activity is certified by Makerere University and taught by CVT staff. It is designed for mental health counselors working in Northern Uganda and offers them an opportunity to strengthen their skillset and achieve an advanced level of competence in trauma-focused mental health counseling. The professional education and training activities are conducted on an ongoing basis for CVT counselors, as well as delivered to partner organizations. Formal training topics include trauma processing and exposure, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, gender-based violence specific interventions, and Dr. Judith Herman’s Trauma Therapy Model. After receiving training, counseling participants receive clinical supervision to ensure high quality services to survivors. This includes a diverse combination of coaching, emotional support, and creating safe space for service delivery reflection. CVT’s expert psychotherapists also provide “live” supervision to engage directly during client sessions and provide detailed coaching and co-therapy. After completing CVT’s educational programs, all counseling professionals have the ability to effectively treat the mental health needs of trauma survivors long into the future.

Women and girls participating in CVT services are referred by community leaders, partner organizations, self-referrals or referrals from past clients, community education events, and community word-of-mouth. Community outreach, in particular, is an effective tool to educate communities and reach vulnerable women. Each client goes through an intake process that is used to determine if CVT services will be the best fit, since CVT services are aimed at vulnerable community members with high levels of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and concerns with somatic and behavioral functioning.

340 direct beneficiaries (160 women per year, 20 total counselors) and 2,000 indirect beneficiaries

UN Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- Why do you think capacity building for local mental health professionals is important for this project?

- How do you think group counseling makes a difference in trauma recovery?

- Why is it important for counseling and treatment to be culturally relevant?

How the Grant Will be Used

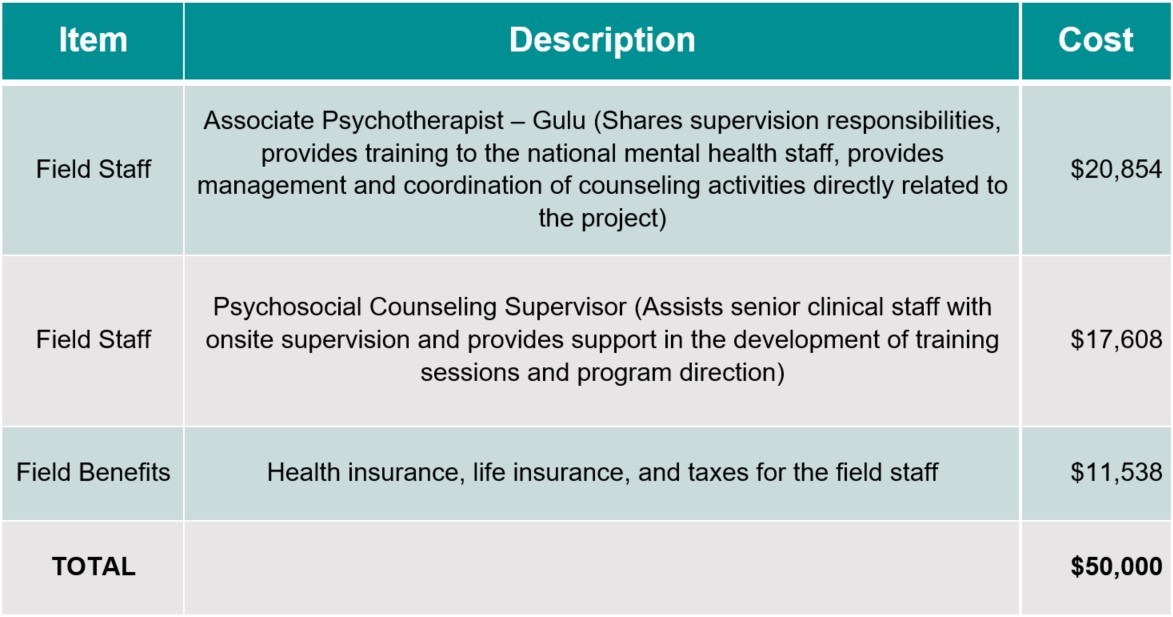

Together Women Rise’s grant of $50,000 over 2 years will help fund the following:

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love CVT’s focus on the rehabilitative care of women and girls who were kidnapped and trafficked into becoming child soldiers or sex slaves of male combatants of the Lord’s Resistance Army. CVT offers interdisciplinary, holistic, and broad-based healing care for the trauma and torture experienced by their beneficiaries. CVT is also training and building capacity of local mental health professionals to understand, identify, support, and treat survivors of torture and trauma in these communities for a long time to come.

Evidence of Success

CVT has proven to be effective in reducing the impact of trauma on a survivor’s mind and body, and is a global human rights leader adding to the field of torture rehabilitation through training, research, and advocacy. The biggest part of CVT’s work is interdisciplinary, rehabilitative care. This means they provide a range of services that may include psychotherapy, social work, physical therapy, and nursing to provide healing for the whole person. In 2020, CVT provided rehabilitative care and restored hope to 2,329 individual survivors and over 20,000 of their family members globally. Across the world, CVT empowers survivors of torture to heal from the violence that destroyed their lives.

Voices of the Girls

“During my short time with group members, I have experienced so many changes in myself, especially in the way I see my life. I used to fear people and feel scared and suspicious when meeting or even talking to any other person, but the way this service has gradually changed my ways of socializing with people is wonderful.” — Basco*, CVT Uganda Client

“Most of the time I used to blame myself that [being captured] it was my fault, but by attending the group session I realized that it was not my own making but rather it was due to the order of the commanders that forced me to do all these atrocities. Sessions seven (grief processing) and six (trauma processing) helped me so much to talk about my past and relieved me from the burden.” — Angeline*, CVT Uganda Client

“When I joined the group counseling, I realized that I was not the only one who went through that, other people are also facing the same kind stigma, I also realized that I cannot change the past but rather to look forward in rebuilding my future.” — Anonymous*, CVT Uganda Client

“After hearing from many people in this group who have also gone through the same or even worse more painful experiences than mine, from today I will leave these useless worries and feelings of guilt. The nightmares have already reduced, I sleep better now, and I will start to focus on taking care of myself and my family.” — P*, CVT Uganda Client

“I attempted suicide in December 2020 because my wife left me. I was hospitalized for two weeks. When my friend heard about CVT, he brought me to CVT for services. I was still weak back then. I thank God I came because I learned a lot. I learned that I am not the only one with problems. I can now live. I feel stronger physically and emotionally because of the counselling and support from my group members.” — Anonymous*, CVT Uganda Client

“I attempted suicide in December 2020 because my wife left me. I was hospitalized for two weeks. When my friend heard about CVT, he brought me to CVT for services. I was still weak back then. I thank God I came because I learned a lot. I learned that I am not the only one with problems. I can now live. I feel stronger physically and emotionally because of the counselling and support from my group members.” — Anonymous*, CVT Uganda Client

“I gained hope again which was not the case before CVT came. Before the counseling therapy I thought that life was useless and has no meaning … [Now, I can] take care of myself such as eating well, reducing alcohol consumption, and I started dressing with attention choosing nice clothes which was not the case before therapy.” —Sara* CVT Client

*Note, Client names are changed for their protection. Clients may also choose to remain anonymous.

About the Organization

CVT was founded on the recommendation of Minnesota Governor Rudy Perpich in 1985. CVT was the first rehabilitation center for torture survivors in the United States, and remains one of the largest organizations of its kind in the world. Their work began in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area of Minnesota, serving immigrants from war-torn countries, and in 1999, CVT launched its first international direct services program in West Africa. Today, their international rehabilitation programs operate in Jordan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Iraq, and Uganda.

Where They Work

Uganda is located in East-Central Africa, west of Kenya, east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in an area slightly more than two times the size of Pennsylvania. The Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Tanzania border it. The population of Uganda is 44,712,143 (July 2021 est.).

Uganda has one of the youngest and most rapidly growing populations in the world. Its total fertility rate is among the world’s highest at 5.8 children per woman. Except in urban areas, actual fertility exceeds women’s desired fertility by one or two children, which is indicative of the widespread unmet need for contraception, lack of government support for family planning, and a cultural preference for large families. High numbers of births, short birth intervals, and the early age of childbearing contribute to Uganda’s high maternal mortality rate. Gender inequities also make fertility reduction difficult; women on average are less-educated, participate less in paid employment, and often have little say in decisions over childbearing and their own reproductive health.

The birth rate in Uganda is 41.6 births/1,000 population (2021 est.), and the death rate is 5.17 deaths/1,000 population (2021 est.). Mother’s mean age at first birth is 19.4 years (2017 est.). The maternal mortality rate is 375 deaths/100,000 live births (2017 est.), and the infant mortality rate is 31.49 deaths/1,000 live births. Life expectancy for the total population is 68.58 years: for men it is 66.34 years, and for women it is 70.9 years (2021 est.).

The percentage of the total population who are literate is 76.5. The male literacy rate is 82.7 percent, and the female literacy rate is 70.8 percent (2018). The percentage of the population below the poverty line is 21.4 percent (2016 est.).

A closer look at child soldiers in armed conflicts

Thousands of children are recruited and used in armed conflicts across the world. Between 2005 and 2020, more than 93,000 children were verified as recruited and used by parties to conflict. Warring parties use children not only as soldiers in combat, but in functions such as scouts, cooks, guards, messengers, sex slaves, and more. The use of children for acts of terror, including as suicide bombers, has emerged as a phenomenon of modern warfare.

There are many reasons why children become part of an armed force or group. Some are threatened, coerced or manipulated. Some are beaten into submission. Others are driven by poverty, compelled to generate income for their families. Others join for survival or to protect their communities.

For example, throughout the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, children have been abducted and made to serve as soldiers. While most are male, it is estimated over a third are female, used mainly as domestic and sexual servants, but sometimes as fighters. A report by Child Soldiers International (CSI) interviewing more than 200 female former child soldiers following their escape from local militia groups found that many girls joined due to poverty and (significantly) a lack of access to education with little hope to better their situations. Sometimes they were encouraged by their parents, who thought that providing their children to the armed group would protect the family against attacks and looting.

No matter their role, or how they are recruited, child participants in conflict are commonly subject to abuse and gender-based violence, and most of them witness death, killing, and sexual violence. Many are forced to commit violent acts, and they can suffer serious long-term psychological consequences.

Whether children are accepted back into society depends on several factors, including their reason for being involved with the conflict, and the perceptions of their families and communities. Some children who attempt to reintegrate are viewed with suspicion or rejected. Girls are often stigmatized because of the assumption they were used for sex. Some of the girls interviewed in the CSI study were actually considering going back to the militia groups because they were not welcome back in their homes or communities and felt stigmatized.

Source Materials

https://sageclinic.org/blog/healing-art-therapy/ https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/the_benefits_art_therapy_can_have_on_mental_and_physical_health

https://www.musictherapy.org/research/factsheets/

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/nepal/

https://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/nepal.htm