Mission

BARKA empowers the people of Burkina Faso to thrive by partnering with communities to break the poverty cycle – permanently. BARKA’s work focuses on Water, Women, and Agriculture. “Barka” is an African word of gratitude, blessing, and reciprocity.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

About a quarter of the world’s population is reproductive-aged women, the majority of whom bleed monthly for 35-40 years. However, more than 500 million women and girls experience period poverty. In Burkina Faso, three out of four women experience period poverty, and menstrual management is hindered by lack of access to information, affordable products, soap and water, privacy, adequate facilities to change/wash, menstrual pain management, disposal/storage, and an enabling environment. The gendered environment surrounding menstruation, a culture of silence, taboos and misconceptions – often carried on by religious and cultural traditions embedded in a patriarchal and discriminatory society – only serve to amplify the challenges women and girls already face by excluding, shaming, and diminishing them.

About a quarter of the world’s population is reproductive-aged women, the majority of whom bleed monthly for 35-40 years. However, more than 500 million women and girls experience period poverty. In Burkina Faso, three out of four women experience period poverty, and menstrual management is hindered by lack of access to information, affordable products, soap and water, privacy, adequate facilities to change/wash, menstrual pain management, disposal/storage, and an enabling environment. The gendered environment surrounding menstruation, a culture of silence, taboos and misconceptions – often carried on by religious and cultural traditions embedded in a patriarchal and discriminatory society – only serve to amplify the challenges women and girls already face by excluding, shaming, and diminishing them.

Menstruation affects all aspects of an individual’s life. The inability of women and girls to effectively manage their periods deprives them of certain basic rights, including those related to education, work, health, non-discrimination, and social justice. In Burkina Faso, only 26 percent of women report having everything they need to manage menstruation. Most use recycled cloth or paper to manage their periods, leading to lack of comfort and confidence. In fact, 82 percent (rural) and 26 percent (urban) use recycled cloth, with less than 15 percent reporting soap/water available where they change. Only 68 percent of households have access to clean water essential for menstrual management. Access to disposable pads improves work attendance by 21 percent; however, disposable pads are of poor quality and are often unaffordable.

Menstruation is shrouded in silence, shame, and taboos, resulting in dozens of systemic barriers that restrict and diminish those who menstruate. These barriers impact ability to participate meaningfully and achieve in school and work, in community, religious, and social life, and they negatively affect physical and psychological health and safety. Ultimately, quality of life as individuals is diminished, and gender equality is compromised.

The stigma associated with menstruation is omnipresent, in all societies, but is even stronger in low-resource settings. Since it is a taboo, it is talked about as little as possible. The silence around periods inhibits intervention, research, and investment of actors in the field. In Burkina Faso, it has been reported that 90 percent of women didn’t know what happened at menarche, and 79 percent were afraid. Because of taboos, many adult women still don’t know why they menstruate, are unfamiliar with the basic principles of menstrual management, and don’t communicate these issues with their daughters, repeating the cycle for generations.

The stigma associated with menstruation is omnipresent, in all societies, but is even stronger in low-resource settings. Since it is a taboo, it is talked about as little as possible. The silence around periods inhibits intervention, research, and investment of actors in the field. In Burkina Faso, it has been reported that 90 percent of women didn’t know what happened at menarche, and 79 percent were afraid. Because of taboos, many adult women still don’t know why they menstruate, are unfamiliar with the basic principles of menstrual management, and don’t communicate these issues with their daughters, repeating the cycle for generations.

Effective menstrual management requires access to information, products, soap and water, privacy, adequate facilities to change and wash, analgesics, safe disposal or storage, and an enabling environment. Without this, women resort to unhealthy practices (reusing disposable pads, storing fabric absorbents under mattresses, etc.), are restricted from income-generating activities, experience high levels of anxiety, and resort to desperate measures (such as transactional sex) to obtain necessary resources (transportation, disposable pads). This increases their risk of contracting reproductive tract and sexually transmitted infections with potentially serious long-term consequences, unwanted pregnancies, and impacts their agency and ability to be full, participating members of their community.

In addition to these unfortunate circumstances are the difficult lives these women lead in general. The average lifespan of a woman in Burkina Faso is 64 years, with an average of 5.7 children (6.9 children in rural areas). Forty-four percent live below the poverty line. Over half of all women are married before the age of 18 and 10 percent before age 15. Burkina Faso has one of the lowest rates of contraceptive use by women globally, and one of the highest maternal mortality rates. Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation and Cutting (FGM/C) in women ages 15 – 49 is 76 percent, however the practice is outlawed and the prevalence is shrinking among younger age groups.

In addition to these unfortunate circumstances are the difficult lives these women lead in general. The average lifespan of a woman in Burkina Faso is 64 years, with an average of 5.7 children (6.9 children in rural areas). Forty-four percent live below the poverty line. Over half of all women are married before the age of 18 and 10 percent before age 15. Burkina Faso has one of the lowest rates of contraceptive use by women globally, and one of the highest maternal mortality rates. Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation and Cutting (FGM/C) in women ages 15 – 49 is 76 percent, however the practice is outlawed and the prevalence is shrinking among younger age groups.

Women are marginalized in many areas of society and have unequal access to education, healthcare and employment. Less than a third of all women are literate. Forty-four percent of women ages 15 –49 years think that a husband/partner is justified in hitting or beating his wife under certain circumstances. When it comes to unpaid care work, 90 percent see it as a woman’s responsibility, and 70 percent do not think that this work should be shared between men and women. Burkinabe women also remain largely underrepresented in the political sphere with less than 10 percent representation in the national assembly, far below the global average of 23 percent. Burkina Faso women have the weakest voices in Africa regarding financial decision making, with a 39 percent gap, followed by a 23 percent gap in average asset ownership.

The Project

BARKA’s Afric’up: Ya Soma project lays the groundwork for menstrual cups in Burkina Faso via programming and distribution. (Afric’up is a play on Africa and UP, and Ya Soma [Yaa sôama] means “it’s good.”) Cups are an ingenious alternative to pads, tampons, or cloth, one that has the power to revolutionize Burkina’s menstrual health development programs. This project improves participants’ quality of life through Menstrual, Sexual and Reproductive Health (MSRH) education, leadership, and economic gain. It will improve participants’ MSRH and well-being, financial agency, ability to participate fully in all aspects of their home, work, social, and religious life, and general MSRH knowledge and ability to manage their periods.

BARKA’s Afric’up: Ya Soma project lays the groundwork for menstrual cups in Burkina Faso via programming and distribution. (Afric’up is a play on Africa and UP, and Ya Soma [Yaa sôama] means “it’s good.”) Cups are an ingenious alternative to pads, tampons, or cloth, one that has the power to revolutionize Burkina’s menstrual health development programs. This project improves participants’ quality of life through Menstrual, Sexual and Reproductive Health (MSRH) education, leadership, and economic gain. It will improve participants’ MSRH and well-being, financial agency, ability to participate fully in all aspects of their home, work, social, and religious life, and general MSRH knowledge and ability to manage their periods.

Sisterhood SARL, a local social enterprise visible with the commercial brand “Menstru’elles,” provides a key component for sustainability through cup sales and distribution as well as economic opportunities for participating women. They are cup pioneers in Burkina Faso, with direct and indirect sales through women ambassadors, and small-scale distribution programs.

BARKA’s community-based approach puts this issue on the nation’s development agenda. This pilot project builds on successful initiatives in Kenya, Tanzania, and Malawi. It will receive national attention through TV, radio, and print journalism in an effort to put menstrual cups on the national radar as a breakthrough in women’s health, and it positions cups to become a part of Burkina’s developmental agenda in areas of health, education, and gender equity.

This project has widespread implications beyond Burkina Faso. Francophone West Africa has been slow to adopt menstrual cups. This is among the first major cup projects in the region. Therefore, BARKA is approaching this pilot as the creation of a new model adapted for West Africa. BARKA aims to set standards for community acceptance, taxation, importation, sales, and a West African religious and cultural context that could be expanded regionally as it scales.

Menstrual cups are unknown in Burkina. They are an innovative technological breakthrough set apart from other menstrual products: they are safe, convenient, comfortable, eco-friendly, and produce no waste (unlike disposable pads or tampons which are not even available for anyone but the wealthiest Burkinabè). They are also easy-to-use, clean, private, and will even promote confidence. Many existing menstrual products in Burkina have the reverse effect, increasing fear and shame, anxiety of leaking, on top of resulting in physical discomfort. A 2013 UNICEF study showed that 72 percent of Burkinabè girls suffer from stress and lack of self-confidence during this period. No NGO has ever promoted cups in the country before and knowledge of cups is limited even among MH project managers. There is a serious need to introduce cups on a national scale.

Menstrual cups are unknown in Burkina. They are an innovative technological breakthrough set apart from other menstrual products: they are safe, convenient, comfortable, eco-friendly, and produce no waste (unlike disposable pads or tampons which are not even available for anyone but the wealthiest Burkinabè). They are also easy-to-use, clean, private, and will even promote confidence. Many existing menstrual products in Burkina have the reverse effect, increasing fear and shame, anxiety of leaking, on top of resulting in physical discomfort. A 2013 UNICEF study showed that 72 percent of Burkinabè girls suffer from stress and lack of self-confidence during this period. No NGO has ever promoted cups in the country before and knowledge of cups is limited even among MH project managers. There is a serious need to introduce cups on a national scale.

This project will first and foremost provide a greater degree of self-sufficiency through an improved approach toward menstrual health. Menstrual cups cannot be felt. They are small, bell-shaped receptacles made of medical-grade silicone that are worn internally for up to 12 hours to collect, rather than absorb, blood. They allow users to travel, remain at work, and select their  changing location with more care. Women and girls report feeling greater confidence and freedom during their period when wearing a cup, empowering them not only to physically participate more in daily activities, but also to have the confidence to do so without anxiety and fear. In addition, the project will develop the leadership potential of trainers who will curate support systems and networks for menstruators in the community who participate in the workshops and use a cup. Collectively, these women will address a seldom-discussed topic and tackle menstrual stigma, harmful traditional practices, and cultural misconceptions. In so doing, they will develop their own leadership potential, and emerge as more self-sufficient leaders within their community.

changing location with more care. Women and girls report feeling greater confidence and freedom during their period when wearing a cup, empowering them not only to physically participate more in daily activities, but also to have the confidence to do so without anxiety and fear. In addition, the project will develop the leadership potential of trainers who will curate support systems and networks for menstruators in the community who participate in the workshops and use a cup. Collectively, these women will address a seldom-discussed topic and tackle menstrual stigma, harmful traditional practices, and cultural misconceptions. In so doing, they will develop their own leadership potential, and emerge as more self-sufficient leaders within their community.

This project will unfold in distinct stages:

Pre-planning: Establish Project Coordination Mechanisms and Stakeholder Engagement

In this inception stage, management and Measurement & Evaluation tools are determined and meetings are held with major stakeholders to engender their support. These include traditional and religious leaders. The project team will establish partnerships with ten local Community Health Centers (CSPS) and five Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) associations, who will select two women to participate. BARKA will set up logistical arrangements for Stage I training, purchase cups, and assemble Cup Kits, and integrate feedback from stakeholder meetings into training materials. Cup Kits include a menstrual cup, a small metal pan to sterilize the cup (by boiling before use), locally made PH-neutral soap, a cloth bag for cup storage, and an illustrated leaflet on safe cup usage.

Stage I: Initial Training in MSRH and Introduction to the Menstrual Cup

This stage consists of a 16-hour training over two days for 30 women, conducted by a Master Trainer, to provide a comprehensive introduction to the menstrual cup. Local menstrual health experts from BARKA and Menstru’elles will lead this training within a local cultural context for women to help them better understand their rights and available in-country resources.

This stage consists of a 16-hour training over two days for 30 women, conducted by a Master Trainer, to provide a comprehensive introduction to the menstrual cup. Local menstrual health experts from BARKA and Menstru’elles will lead this training within a local cultural context for women to help them better understand their rights and available in-country resources.

Post-training, participants will use the cup for three months to become familiar and comfortable with it (achieve “cup confidence”) prior to the next round of training. The all-female project staff will provide individualized support as needed during that time. Participants will be encouraged to learn from each other and compare experiences in a peer-to-peer approach. Lastly, BARKA will finalize contracts for the 24 women who advance to Stage II training.

Stage II: Training of Trainers (ToT); Menstrual Cup Distribution

In Stage II Training, 24 women from Stage I will become trainers to conduct workshops in their community. Training will include MSRH, menstrual cups, broader gender issues such as FGM/C and gender-based violence (GBV), the basics of data collection, and education pedagogy where they will also practice and receive feedback. A participatory section will seek input on recruitment, advertising, key topics to cover in workshops, workshop logistics, and other key points to maximize impact. Workshops will be run by pairs of trainers. The project team leading the training will emphasize the need to serve the most vulnerable women. The trainers know their community and will approach this task with integrity.

Trainers play a significant role in the successful outcome of this project and are given a great deal of responsibility to autonomously manage workshops and support of cup users. BARKA and Menstru’elles will sign a contract with each of the 24 trainers, outlining their responsibilities including leading workshops providing phone and/or in-person support on cup usage over 3 months, and collecting M&E data. Trainers will be paid for their time (at a rate far higher than the national average) and will oversee a modest budget (covering phone, food and water, transport) to arrange their workshops. BARKA will also rely on trainers to secure local schools and Community Health Clinics (CHCs) to provide free, private spaces at which to meet.

Trainers play a significant role in the successful outcome of this project and are given a great deal of responsibility to autonomously manage workshops and support of cup users. BARKA and Menstru’elles will sign a contract with each of the 24 trainers, outlining their responsibilities including leading workshops providing phone and/or in-person support on cup usage over 3 months, and collecting M&E data. Trainers will be paid for their time (at a rate far higher than the national average) and will oversee a modest budget (covering phone, food and water, transport) to arrange their workshops. BARKA will also rely on trainers to secure local schools and Community Health Clinics (CHCs) to provide free, private spaces at which to meet.

Each trainer will be responsible for recruiting 50 participants, administering questionnaires, dispersing Cup Kits, and providing support and follow-up to workshop participants. This will yield 1,200 (24×50) Stage II beneficiaries. Project staff will manage cup inventory, payroll, in-person workshop monitoring, as well as provide technical support to trainers as they provide phone and in-person support to new cup users for the next three months. Trainers will do their best to serve clusters of women within families (mothers, daughters, sisters, etc.) to increase uptake and provide opportunities to learn from each other.

Stage III: M&E, Lessons Learned and Advocacy

M&E is integrated into program activities, engaging trainers to maximize efficiency and data quality.

M&E is integrated into program activities, engaging trainers to maximize efficiency and data quality.

To measure cup usage and uptake in different settings, BARKA is focusing on one urban area of central Ouagadougou, and one peri-urban environment in the city outskirts. Demographic information concerning health and wealth may diverge between these two areas, enabling BARKA to glean valuable information from both geographic zones about cup usage and uptake.

For every woman this project benefits, there will be indirect benefits for up to seven others (six children and her husband). That translates to 1,230 women directly served and 8,610 indirectly served, half of whom are expected to be girls and women. Young boys will be sensitized by the increased awareness mothers gain through their training. The sensitization this project imparts goes beyond menstrual cups and menstrual health, contributing to breaking the silence on this taboo topic and creating a more menstrual-friendly environment with less shame and secrecy.

UN Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- How do you think menstrual cups could affect women’s mental health?

- How are menstrual cups a step toward gender equality?

- Why is the media campaign associated with this project an important component?

How the Grant Will be Used

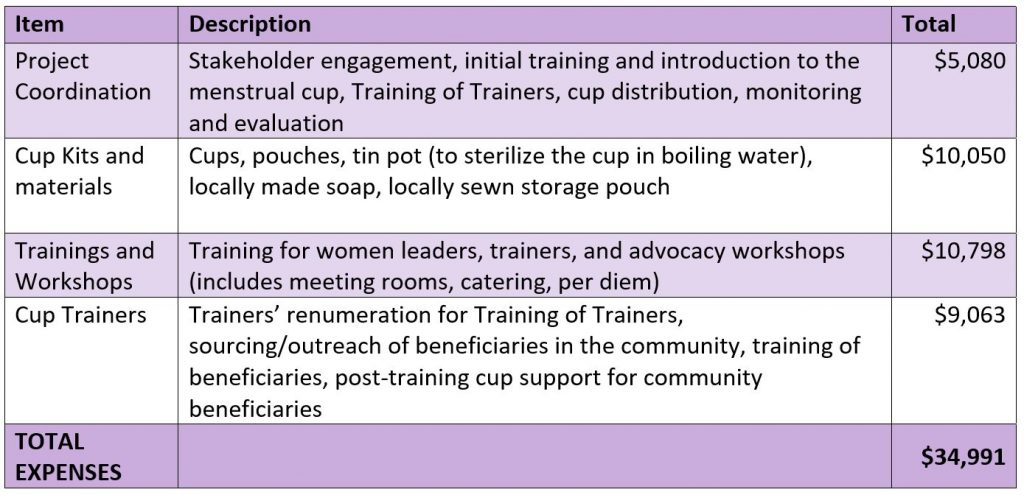

DFW’s grant of $34,991 will be used for the following:

Why We Love This Project/Organization

The BARKA Foundation is deeply respectful and connected to the communities it serves. This fosters a greater investment from the entire community, brings community members into the decision-making process of project implementation, and enables greater autonomy and local leadership – all of which are key to sustaining long-term benefits and impacts after project completion.

Evidence of Success

BARKA’s WASH projects have provided access to clean drinking water to more than 25,000 rural villagers, some of whom previously had to walk up to 7 kilometers for water. Training of water committees in each village has ensured long-term sustainability of project inputs (wells, latrines), all of which are still working after 5+ years.

Dandantiri, one of the small villages BARKA worked with in 2015’s five-village WASH project, returned to BARKA after project completion. They raised $1,000 to build their own school and needed another $1,000 to complete the project. This was a result of the social mobilization component of BARKA’s comprehensive WASH program, designed to foster leadership, autonomy, and resilience. BARKA completed the funding for their school. The Ministry of Education cited BARKA for this action.

Dandantiri, one of the small villages BARKA worked with in 2015’s five-village WASH project, returned to BARKA after project completion. They raised $1,000 to build their own school and needed another $1,000 to complete the project. This was a result of the social mobilization component of BARKA’s comprehensive WASH program, designed to foster leadership, autonomy, and resilience. BARKA completed the funding for their school. The Ministry of Education cited BARKA for this action.

BARKA’s work on the Menstrual Health Coalition has helped to break the silence around the taboo of menstruation through four consecutive years of national events on Menstrual Health Day in Burkina Faso. On May 28, 2020, the Minister of Education stated that menstrual health is now a priority issue for the new educational curriculum being developed.

BARKA’s MH project leaders sensitized 6,500 high school girls, most of whom had never received any prior MH education about the menstrual cycle and MSRH. Questions students asked before training include: Is it possible for a genitally mutilated girl to have normal menstruation? Can you get pregnant by kissing a boy? When you have your period and a boy touches you, can you get pregnant? Why does blood come out?

Voices of the Girls

“I was able to insert and remove the cup without any problems. I haven’t had a leak, it’s comfortable and you forget you have your period! No more pieces of cloth. I told my friends who are very interested.”

- Kaboré, age 40

“The cup is very comfortable and it does not leak. No more pads, I’ll use it until my menopause.”

- Sanfo, age 36

“To be honest, I was pleasantly surprised. The first day when I put it in, I carried the cup and a pad, because I was afraid of staining my clothes. But I didn’t! I went home around 3 p.m. and not even a drop on the pad. I told a friend on the campus about it and we will get her a cup.”

- Tia, student at the university, age 19

“The poor hygienic management of menstruation is the cause of school dropout for young girls.”

- Burkina Minister of Education, PR Stanislas Ouaro

About the Organization

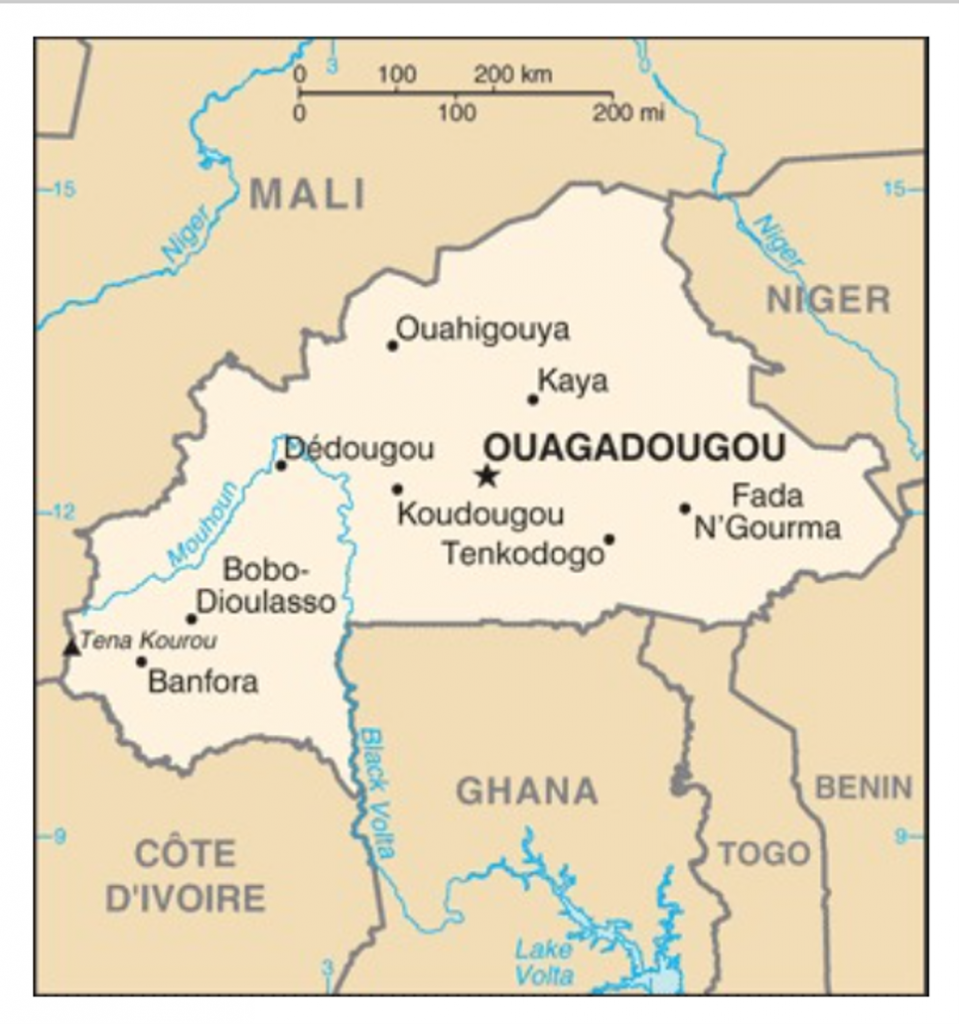

BARKA Foundation is a Maine-based nonprofit organization co-founded by Ina and Esu Anahata in 2006. In Burkina Faso, BARKA is headquartered in Fada N’Gourma, the capital of the eastern region, and works in the East, Center-East, and Center regions. It is affiliated with the United Nations and has Special Consultative Status with the UN’s Economic and Social Affairs Division. BARKA’s vision is for everyone in Burkina Faso to have clean drinking water, improved sanitation, knowledge of basic hygiene, empowered women and girls, and skills to mitigate and adapt to climate change. BARKA provides many services:

- – WASH/WASH-in-Schools: Community-led WASH projects in rural villages and schools; emphasis on training water committees to sustain impacts through good governance.

- – Menstrual Health Program: Sensitization programs for students, teachers, and parents in high schools, including establishment of school health clubs (latrine maintenance, peer-to-peer menstrual health support) and construction of menstrual health cabins; teacher training (via UNICEF) for MH project leaders; and national menstrual health advocacy.

- – Theatre: professional theatre troupe creates original plays to sensitize rural villages and schools on various subjects, e.g., the role of women in water resource management, improved agroecology techniques, etc.

- – Education: Development of long-lasting, mutually beneficial relationships between US and Burkina schools and communities. Burkina: school construction; online access for high schools; provision of computers, tablets, bikes, cameras, handwashing stations, water carriers; soccer competitions, photo club, and health clubs. USA: service-learning programs to develop leadership and cultural competence.

BARKA’s WASH projects focus on entire rural communities (ages 0 – 90), which are comprised of large family clusters of 10 – 20 people in compounds consisting of mud huts with thatched roofs. These are subsistence farmers who grow almost all their own food. Eighty-five percent live well below the poverty line on less than one dollar per day, their annual income being seasonal. In the eastern region where BARKA is based, less than 50 percent have access to clean water and 97 percent practice open defecation.

BARKA’s WASH projects focus on entire rural communities (ages 0 – 90), which are comprised of large family clusters of 10 – 20 people in compounds consisting of mud huts with thatched roofs. These are subsistence farmers who grow almost all their own food. Eighty-five percent live well below the poverty line on less than one dollar per day, their annual income being seasonal. In the eastern region where BARKA is based, less than 50 percent have access to clean water and 97 percent practice open defecation.

BARKA’s MH projects to date have focused on high school girls ages 12-20. For Burkinabè girls in school, lack of menstrual resources often leads to the abandonment of their education.

- – 17 percent complete middle school and only 6 percent complete high school

- – 52 percent of schools do not have access to water

- – 24 percent do not have latrines and 62 percent do not have separate latrines for girls

- – 69 percent do not provide garbage cans to throw away used hygienic protection

- – 45 percent of girls restrict their activities during menstruation, leading to an absentee rate for girls of five days a month because of their periods

- – 83 percent of girls are unable to change their disposable pads at school.

Where They Work

Burkina Faso is a landlocked nation in West Africa with a population of 21 million and one of the world’s highest population growth rates at three percent. The country is the size of Colorado yet has more than 60 ethnic groups. It is ranked 182 out of 189 countries on UNDP’s Human Development Index. Burkina has the world’s 3rd youngest population (median age is 16), with more than 65 percent under age 25. It is the third most illiterate country in the world with a 28.7 literacy rate. Eighty-five percent of the country has no electricity. As a Sahelian country, it is rare to receive any rainfall for eight months out of the year.

A closer look at how menstrual health is a key to women’s time, education, and their ability to control their body autonomy and freedom of movement – all of which are critical in the fight for gender equality.

It is difficult for many of us to imagine a man feeling ashamed or inadequate for five days every month. Yet hundreds of millions of women around the world endure five monthly days of unspeakable shame and humiliation – first as teens and then continually, every month, for decades. Around the world, there are numerous examples of how women’s dignity and human rights are violated because of a basic physiological bodily function.

Imagine a 15-year old boy cast to sleep outside his home every month in a space cordoned off from the rest of the family. He must wear the same clothes and eat with the same utensils for those five days. He is considered unclean and may not enter the house until the five days are up. (Some young girls in India take this treatment for granted.)

Imagine that same young man misses school five days a month to avoid teasing and exclusion. The situation worsens as he gets older, to the point that he drops out. (One in ten girls in Africa miss school when menstruating, which leads to higher dropout rates. Eighty-eight percent do not have access to sanitary products.)

Imagine a grown man being told that for five days a month he can’t drink milk because he might contaminate the herd, and during that same five days he can’t plant any nuts because he will cause a poor crop yield. (These myths are propagated in Uganda.)

Imagine a man wearing underwear made of leaves, filthy rags, or newspapers for five continuous days every month until painful urogenital irritation erupts. Despite the discomfort, he cannot speak of it and there are no treatments available. In fact, if he admitted to using any kind of sanitary towel, he would be further ostracized. (In Sierra Leone, some groups believe that a used sanitary towel can make a person sterile. In Nigeria, the Igbo tribe believes that a burned menstrual cloth causes itchy skin, cancer, and infertility.)

This is just one face of gender inequality. Providing menstrual cups, sanitary conditions, and education are critical steps to helping women regain the dignity and respect they deserve.

Source Materials

https://www.unfpa.org/menstruationfaq#menstruation%20and%20human%20rights

https://iwda.org.au/what-is-it-like-to-have-your-period-in-a-developing-country/

https://www.plan.org.au/news/gender/menstruation-lets-stop-the-myths/