Mission

Jacaranda Health’s mission is to transform maternal healthcare in low resource settings with high-quality, low-cost, and respectful maternity services.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

Every day, 830 maternal deaths occur around the world – 35 every hour. The majority are in sub-Saharan Africa. More than 70 percent of maternal deaths occur because of complications of pregnancy and childbirth, and 85 percent of newborn deaths occur because of complications due to preterm birth. Kenya has one of the highest maternal mortality rates at 385 deaths per 100,000 deliveries. Adolescent girls account for 10 percent of these deaths. The three leading causes of maternal death are obstetric hemorrhage (51.1 percent), hypertensive disorders associated with pregnancy (19.7 percent), and pregnancy related infection (12.5 percent). Sadly, these conditions could be prevented if mothers had better access to higher quality care.

Ironically, the presence of a skilled birth attendant has actually increased from 40 to 60 percent in the last eight years, yet maternal mortality rates remain unchanged. The reason for this is a serious lack of quality, adequately-trained care – especially at government facilities where maternity care is free and where 80 percent of poor Kenyan women give birth. In fact, 60 percent of maternal deaths can be traced back to a gap in quality care, the primary cause of maternal death. Nurse midwives attend 90 percent of facility-based deliveries in government hospitals. Unfortunately, they have typically scored under 50 percent on skills related to Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC). These life-saving skills equip providers to rapidly recognize and manage complications during pregnancy, childbirth, and the post-partum period. These nurse midwives receive numerous classroom-based trainings yet continue to score poorly on life-saving skills because they do not get enough hands-on training. As a result, there are harrowing firsthand accounts from women who have experienced poor quality of care in public hospitals.

Ironically, the presence of a skilled birth attendant has actually increased from 40 to 60 percent in the last eight years, yet maternal mortality rates remain unchanged. The reason for this is a serious lack of quality, adequately-trained care – especially at government facilities where maternity care is free and where 80 percent of poor Kenyan women give birth. In fact, 60 percent of maternal deaths can be traced back to a gap in quality care, the primary cause of maternal death. Nurse midwives attend 90 percent of facility-based deliveries in government hospitals. Unfortunately, they have typically scored under 50 percent on skills related to Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC). These life-saving skills equip providers to rapidly recognize and manage complications during pregnancy, childbirth, and the post-partum period. These nurse midwives receive numerous classroom-based trainings yet continue to score poorly on life-saving skills because they do not get enough hands-on training. As a result, there are harrowing firsthand accounts from women who have experienced poor quality of care in public hospitals.

These quality gaps disproportionately affect low-income women in peri-urban and rural areas. This poor quality of care diminishes trust in providers, which in turn negatively affects interest in prenatal and post-partum care. Half of mothers in Kenya report receiving no postnatal care within the highest risk period 48 hours after childbirth and 90 percent of women have an unmet need for family planning at three months postpartum.

Pregnant women and new mothers need access to better care when they reach a facility. To achieve this, new health worker training methods must be instituted. To date, traditional approaches have focused on offsite, classroom-based training models. These interventions are expensive as they require funding for health worker transport, per diem, and accommodation during the trainings, and take health workers out of health facilities during the trainings, resulting in human resource shortages during these activities. Beyond clinical skills, a supportive work environment promotes positive behaviors and attitudes which affect both the provider’s emotional health as well as how they treat mothers during childbirth. There is a critical need to go beyond one-time, didactic training to empower midwives with a tailored, context-specific mode of training and mentorship to achieve safer, respectful maternity care.

Pregnant women and new mothers need access to better care when they reach a facility. To achieve this, new health worker training methods must be instituted. To date, traditional approaches have focused on offsite, classroom-based training models. These interventions are expensive as they require funding for health worker transport, per diem, and accommodation during the trainings, and take health workers out of health facilities during the trainings, resulting in human resource shortages during these activities. Beyond clinical skills, a supportive work environment promotes positive behaviors and attitudes which affect both the provider’s emotional health as well as how they treat mothers during childbirth. There is a critical need to go beyond one-time, didactic training to empower midwives with a tailored, context-specific mode of training and mentorship to achieve safer, respectful maternity care.

The Project

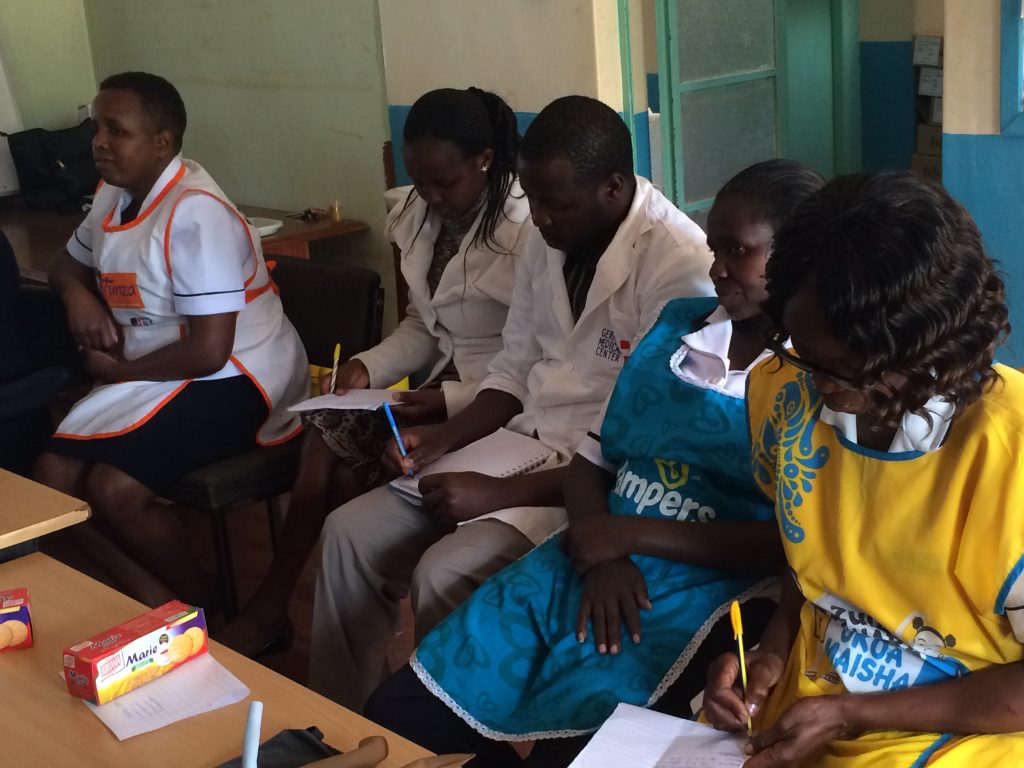

Jacaranda Health (JH) improves the quality of care in public hospitals. Through its Super Nurses for Maternal Health program, JH is creating a new generation of quality-oriented and patient-centered nursing leaders in Kenya. JH has developed a model of on-site mentorship focused on Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care as well as basic obstetric care. Through this program, JH deploys a team of trained midwife mentors across a network of public facilities. These mentors work alongside providers to observe and document challenges. They also provide simulation drills to address skill gaps and context-specific continuing medical education to address knowledge gaps. This approach has equipped 300+ predominantly female nurses with significant and sustained improvements in general and emergency obstetric skills, reflected in a 50 percent improvement in newborn resuscitation scores and reduced complications such as postpartum hemorrhage.

DFW’s one-year grant supports the development of Kenya’s first Nurse Mentor Training Center, which will include a simulation/training lab, nurse mentor recruitment, and training/deployment. This training center will apply JH’s successful model of on-site mentorship and will create a pipeline of strong midwife mentors who will help change the culture of midwifery across Kenya. In addition, this program is anticipated to provide a minimum 30 percent improvement in neonatal resuscitation and partograph completing. (A partograph is an essential tool for monitoring labor.)

DFW’s one-year grant supports the development of Kenya’s first Nurse Mentor Training Center, which will include a simulation/training lab, nurse mentor recruitment, and training/deployment. This training center will apply JH’s successful model of on-site mentorship and will create a pipeline of strong midwife mentors who will help change the culture of midwifery across Kenya. In addition, this program is anticipated to provide a minimum 30 percent improvement in neonatal resuscitation and partograph completing. (A partograph is an essential tool for monitoring labor.)

JH will run two cohorts of five mentors each at the Training Center, and those 10 mentors will serve 30 government hospitals, training approximately 450 frontline maternity nurses, 330 of whom are women. JH’s graduate mentors will be responsible for driving skill improvements in line with previous results from the mentorship program. In 2017-2018, the performance of mentored government facility nurses on basic obstetric skills improved to 88 percent, and teamwork and communication scores improved by 54 percent. Most importantly, all scores sustained at approximately 90 percent levels for six months after the intervention period. These facilities serve more than 30,000 deliveries per year. By 2020, JH aims to reach 50 public hospitals in the five most populous counties in Kenya and anticipates reaching more than 240,000 women and babies in total. Those counties account for approximately 40 percent of Kenya’s maternal and neonatal mortality. The recipients of care in public facilities are primarily women in the lowest economic levels: approximately 67 percent of low income women delivery in public facilities compared to 10 percent in private facilities.

The center will be a small training facility focused on in-depth courses for Kenya’s next generation of nurse mentors. The trainers will work closely with Jacaranda Maternity, JH’s busy maternity hospital that has been independently certified as the highest-quality maternity hospital in the country. JH has already developed a unique curriculum for training mentors and has piloted it successfully with four mentors to date. This is a month-long, hands-on program that consists of three key components: (a) training in simulation and best practices in coaching and mentoring, (b) a week rotation in Jacaranda Maternity, and (c) shadowing an existing nurse mentor in a partner public hospital. The details and chronology of the program are as follows:

The center will be a small training facility focused on in-depth courses for Kenya’s next generation of nurse mentors. The trainers will work closely with Jacaranda Maternity, JH’s busy maternity hospital that has been independently certified as the highest-quality maternity hospital in the country. JH has already developed a unique curriculum for training mentors and has piloted it successfully with four mentors to date. This is a month-long, hands-on program that consists of three key components: (a) training in simulation and best practices in coaching and mentoring, (b) a week rotation in Jacaranda Maternity, and (c) shadowing an existing nurse mentor in a partner public hospital. The details and chronology of the program are as follows:

Activity one: develop training center and design program

This training center would be replicable in low-resource contexts but will deploy best global practices.

- Develop curriculum – JH will update its existing nurse mentor training curriculum with a module focused on simulation training, which will highlight communication and teamwork skills and patient-centered, respectful care.

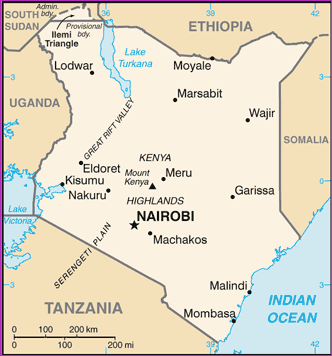

Design and equip training center – The training center will be a small three-room building consisting of a skills lab for training, and a simulation lab that simulates a normal delivery room equipped with mother and neonatal manikins, a delivery bed, a neonatal resuscitaire, and all other relevant delivery equipment present in a standard delivery room in Kenya. It will also contain video recording equipment that will be used to record all simulation drills conducted. JH will be able to accurately simulate normal and complicated deliveries, with scripts and guidelines for actors who can role-play scenarios. The center will be in leased space next to JH’s Maternity Hospital on the outskirts of Nairobi. JH will equip the facility for the lowest possible cost materials to make it replicable in low-resource settings. (JH estimates just over $10,000 for equipment and furnishings). For example, JH has already created simulation kits by using local tailors because importing kits is four times more expensive.

Design and equip training center – The training center will be a small three-room building consisting of a skills lab for training, and a simulation lab that simulates a normal delivery room equipped with mother and neonatal manikins, a delivery bed, a neonatal resuscitaire, and all other relevant delivery equipment present in a standard delivery room in Kenya. It will also contain video recording equipment that will be used to record all simulation drills conducted. JH will be able to accurately simulate normal and complicated deliveries, with scripts and guidelines for actors who can role-play scenarios. The center will be in leased space next to JH’s Maternity Hospital on the outskirts of Nairobi. JH will equip the facility for the lowest possible cost materials to make it replicable in low-resource settings. (JH estimates just over $10,000 for equipment and furnishings). For example, JH has already created simulation kits by using local tailors because importing kits is four times more expensive.

Activity two: recruit and train the first cohort of nurse mentors

- Recruit mentors – Mentors are sourced from the county hospitals where they will be mentoring other nurses – identified partly by referral from JH’s county partners, and partly based on their prior experience in nurse midwifery and emergency obstetric training as well as their experience/interest with teaching and education.

- Enroll prospective mentors in JH’s mentorship onboarding program – As part of its comprehensive mentorship training process, JH requires prospective mentors to undergo a 3 – 4 week onboarding course. This includes: (a) a week rotation in Jacaranda Maternity, where they are exposed to Kenya’s highest quality maternity care, including person-centered and respectful maternity care, (b) a week shadowing an existing nurse mentor in a public hospital, and understand how to partner with and train government hospital staff, and (c) 1-2 weeks simulation training and learning best practices in coaching and mentoring. The mentors will have a one-week intensive training period at JH’s mentor simulation and training center where they will have refresher training for all relevant emergency obstetric care topics, then learn best practices in how to conduct simulations in their own facilities to train other nurse midwives using similar techniques. All simulation drills will be video-recorded and reviewed by the mentor attendees along with the instructors, which provides a visual learning aid that they can critique and learn from.

Activity 3: Deploy mentors to public hospitals

- Identify pubic hospitals requiring mentor support – Hospitals will be identified in partnership with JH’s three county partners and chosen based on their need for improvement in quality maternal healthcare and a willingness to adapt their scope of practice based on mentor support. JH will work with county partners to determine which hospitals benefit most from the mentorship program.

Conduct baseline needs assessments – At each new facility, a thorough needs assessment will take place including both objective and subjective data. Objective data includes scores regarding EmONC knowledge tests, as well as availability of supplies/standards within the maternity ward. Subjective data includes provider and client perceptions around availability and quality of service as well as communication/documentation. Each facility will be given a scorecard describing their baseline assessment and will set facility-based goals for their mentorship period in conjunction with their nurse mentor.

Conduct baseline needs assessments – At each new facility, a thorough needs assessment will take place including both objective and subjective data. Objective data includes scores regarding EmONC knowledge tests, as well as availability of supplies/standards within the maternity ward. Subjective data includes provider and client perceptions around availability and quality of service as well as communication/documentation. Each facility will be given a scorecard describing their baseline assessment and will set facility-based goals for their mentorship period in conjunction with their nurse mentor.- Begin mentorship with newly trained nurses – Newly trained nurse mentors will spend approximately four months in these new facilities and begin emergency obstetric training as well as targeted simulation training for facility nurse midwives with an emphasis on respectful maternity care. Training and drills will cover a set curriculum but will be expanded based on facility-specific needs. Throughout this time, delivery debriefs will be conducted to monitor success of the mentorship program and improvement over the course of the training period. Nurses will also spend one-on-one time mentoring and educating existing nurses as necessary.

- Conduct end-line assessment – Similar objective and subjective indicators as described in the baseline assessment will be used for the end-line assessment to monitor the level of improvement in care. Each facility will be given an end-line scorecard to compare against their baseline data and self-prescribed facility goals.

This project directly benefits and serves women: three out of four nurses in Kenya are women, four of the five current JH mentors are women, the majority of frontline providers that they support are women, and of course, all maternity patients are women. Mentors will be recruited and selected by JH’s county partners based on their prior experience in nurse midwifery, emergency obstetric and newborn training, as well as their experience/interest with teaching and education. Candidates will be chosen based on their responses to a detailed application as well as a personal interview.

This project directly benefits and serves women: three out of four nurses in Kenya are women, four of the five current JH mentors are women, the majority of frontline providers that they support are women, and of course, all maternity patients are women. Mentors will be recruited and selected by JH’s county partners based on their prior experience in nurse midwifery, emergency obstetric and newborn training, as well as their experience/interest with teaching and education. Candidates will be chosen based on their responses to a detailed application as well as a personal interview.

As this project is part of a broader project related to nurse mentorship, JH has utilized the feedback and experience from their existing nurse mentor team to design and formulate plans for the training center. It is in collaboration with these women and those they have served that JH has determined where the needs are and how they can effectively be met. These existing mentors will be an integral part of the training package. They will help with program design and formulation of education materials, and they will run all simulation drills and deliver relevant health information, including EmONC training. In addition, JH continually seeks input from partner public facilities. The ongoing nurse mentorship program is closely linked with JH’s sister organization, Jacaranda Maternity (JM), one of the highest quality maternity hospitals in Nairobi. Nurses and educators affiliated with JM are among JH’s most valued nurse mentors and have had a significant amount of input in the design of the mentorship program.

JH has developed and implemented robust tools for routine monitoring of its programs, as well as outcome and impact evaluation. JH has historically used tools such as an electronic medical record (EMR) and mobile data collection to track performance across existing hospital operations. Information from these sources is used to create dashboards, which allow teams to monitor their performance every month. In addition, JH’s internal research team also works with research partners, such as the Harvard School of Public Health, to conduct rigorous evaluation of the impacts of their tools and approaches, including randomized controlled trials.

JH has developed and implemented robust tools for routine monitoring of its programs, as well as outcome and impact evaluation. JH has historically used tools such as an electronic medical record (EMR) and mobile data collection to track performance across existing hospital operations. Information from these sources is used to create dashboards, which allow teams to monitor their performance every month. In addition, JH’s internal research team also works with research partners, such as the Harvard School of Public Health, to conduct rigorous evaluation of the impacts of their tools and approaches, including randomized controlled trials.

JH has $200,000 in committed funding from Grand Challenges Canada to expand its partnerships with other counties, including JH’s nurse mentorship activities. This funding will allow JH to scale the program to a total of five counties and 50 public hospitals by the end of 2020. In addition, JH has secured $50,000 for 2019 from the Deerfield Foundation as matched funding to support the setup of this training center. JH’s long-term vision is that the mentorship and training center is self-sustaining. JH estimates that once it is set up, the center costs about $50,000 per year to run. JH anticipates recouping that cost by having government partners and nurse mentors themselves cover the costs of participating in the program. The operating cost is roughly $1,500 per mentor, and JH would charge about $2,000 per participant. The space can also be utilized for off group trainings and one-day Continuing Medical Education courses, for which there is an ongoing demand (and willingness to pay) from partner organizations and government.

Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- Why do you think a physical training center is key to the long-term success of the program?

- What skills do you think the nurse mentors possess that may benefit them beyond the hospital?

- How do you think this program will change the quality of healthcare in Kenya in general?

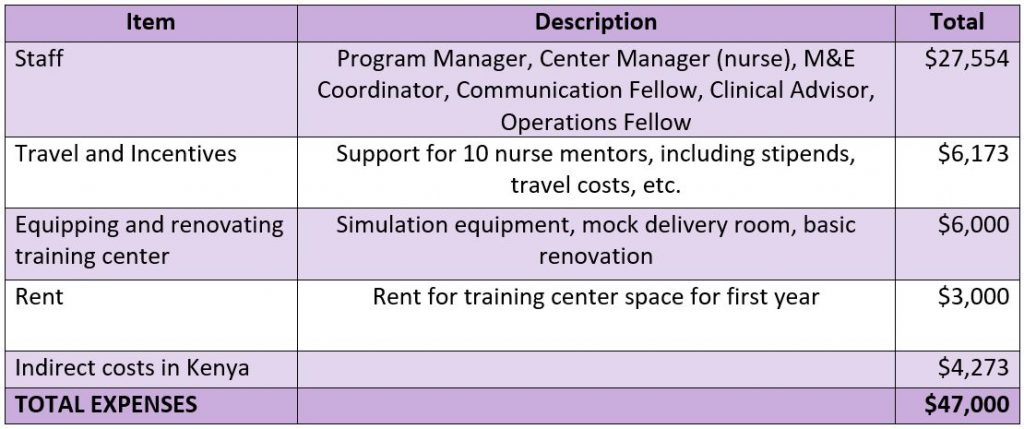

How the Grant Will be Used

DFW’s grant of $47,000 will fund the following:

Why We Love This Project/Organization

Jacaranda Health is creating a pipeline of strong midwife mentors who can help change the culture of midwifery in Kenya and significantly improve health outcomes for mothers and babies.

Evidence of Success

Clients tell stories about coming to Jacaranda from across the city and receiving care that changes their lives. Jacaranda’s Maternity Hospital provides the highest quality maternity care in the country, as shown by their impressive results:

Clients tell stories about coming to Jacaranda from across the city and receiving care that changes their lives. Jacaranda’s Maternity Hospital provides the highest quality maternity care in the country, as shown by their impressive results:

- 99.9 percent maternal survival

- 60 percent fewer maternal complications than nearby public hospitals

- 50 percent uptake of postpartum family planning (four times the national average)

- 90 percent of clients still exclusively breastfeed at nine-weeks postpartum (twice the national average in Kenya).

Jacaranda Health’s public sector partnerships have also had a dramatic impact on mothers and babies in the lowest income segments. These partnerships have grown from three facilities in 2015 to 50+ facilities, serving more than 75,000 women and babies in 2018. When pregnant women or new mothers receive JH’s SMS messages, they are more likely to know danger signs and seek care and are also more likely to take up family planning. In facilities that have Jacaranda-trained mentors, performance on basic obstetric skills has improved from a baseline of approximately 65 percent to a median of 88 percent, and providers are three times as likely to complete partographs, an essential tool for monitoring labor.

In addition, Jacaranda Health has earned many accolades:

- 2013 – East African Health Market Innovation Award

- 2014 – CLASSY Awards for Patient and Family Services

- 2015 – cited by Kiambu County as a benchmark for the Kenya Quality for Health Model

- 2017 – Safecare Level 5 Certification by the PharmAccess Foundation

- 2018 – Geneva Health Forum Award for Innovative and Lifesaving Maternity Care

Voices of the Girls

“This morning a client came in the facility with history of having fainted. At once on reaching the facility the same nurse who participated in the [simulation] drill for eclampsia was the one on duty. As he was taking history from the caretaker the patient started fitting [having seizures] he had to put the patient in bed and was able to administer magnesium sulphate. He notified the driver and the receiving facility and the client was referred. He came and reported to me and he was very happy. He wished I would be going to their facility weekly to do [simulation] drills with them.”

- Nurse Mentor, Mechimeru Model Health Centre, Bungoma County

“We [mentors] are able to go through challenges with them [nurses], so that when we are mentoring them, at least we know and understand what they go through. So we have time with them, we don’t just train them and leave them behind.”

“We [mentors] are able to go through challenges with them [nurses], so that when we are mentoring them, at least we know and understand what they go through. So we have time with them, we don’t just train them and leave them behind.”

- Jane Kageha, Jacaranda Nurse Mentor

“I no longer have fear for delivery. I know how to take care of myself when expectant. I feel supported by the society.”

- Mother at Wangige Sub-County Hospital

About the Organization

Jacaranda Health was established by Nick Pearson in 2011 to improve the quality of maternal health services in Kenya. Initially Jacaranda focused on direct service delivery, building a scalable model for delivering high quality, affordable care to low income mothers and their babies. Jacaranda’s Maternity Hospital serves low income women in peri-urban Nairobi and has grown from serving 600 patients in 2012 to more than 24,000 patients every year – and it has achieved international recognition as one of the highest quality providers in the region, with exceptional health outcomes for mothers and babies.

In 2015, JH began to partner with the public sector to help improve quality of maternal healthcare in the government hospitals. These partnerships have grown from three facilities in 2015 to more than 50 facilities in 2018. JH has begun to see exciting results from simple but effective mobile tools that “nudge” pregnant women and new mothers to seek care at facilities. JH is on track to work with five Kenyan county health systems by 2020 and aims to implement this scalable approach across 50 government hospitals to dramatically improve quality of care for more than 240,000 mothers and babies. Ultimately, JH measures its success by increasing the number of healthy mothers and babies getting service at government facilities.

JH has developed deep ties in the health sector in Kenya and globally. The organization contributes strategy and policy to the Ministry of Health’s (MoH) initiatives on human resources for health. JH’s senior team is involved in the MoH’s technical working groups on Maternal and Child Health and Quality Improvement and mobile health task forces. Meanwhile, JH has built strong ties with county health leadership of three of the most populous counties. JH’s partnerships with professional associations and NGOs help them replicate their model and influence work around quality maternity care. The Nursing Council of Kenya has expressed an interest in using Jacaranda sites as a center for excellence in training.

JH has developed deep ties in the health sector in Kenya and globally. The organization contributes strategy and policy to the Ministry of Health’s (MoH) initiatives on human resources for health. JH’s senior team is involved in the MoH’s technical working groups on Maternal and Child Health and Quality Improvement and mobile health task forces. Meanwhile, JH has built strong ties with county health leadership of three of the most populous counties. JH’s partnerships with professional associations and NGOs help them replicate their model and influence work around quality maternity care. The Nursing Council of Kenya has expressed an interest in using Jacaranda sites as a center for excellence in training.

Jacaranda also works with a number of academic partners to test new innovations and evaluate the impact of programs, including faculty at the Harvard School of Public Health, Duke University, and UCSF.

Where They Work

Kenya is in eastern Africa, bordering Somalia, Tanzania, South Sudan, Uganda, Ethiopia, and the Indian Ocean. It is twice the size of Nevada and home to just under 50 million people. The official languages are English and Kiswahili, although numerous indigenous languages are spoken. The climate varies from tropical along the coast to dry in the interior. There is recurring drought and flooding during the rainy season.

Kenya’s population has exploded since the mid-1900s due to its high birth rate, declining mortality rate, unmet need for family planning, and early marriage and childbearing. In the 1990s, the government decreased emphasis on family planning to focus on the HIV epidemic instead. This combination of factors has resulted in a young population, with 40 percent of Kenyans under age 15. The rapid growth in population takes a toll on the labor market, social services, arable land, and natural resources.

Kenya is also a host country for refugees as well as a source of emigrants. In the 1960s and 70s, Kenyans emigrated to the US, UK, Soviet Union, and Canada for study opportunities. In the 1980s and 90s, Kenya experienced economic and political problems that resulted in a further outpouring of Kenyan students and professionals who sought opportunities in the west and in southern Africa. Conversely, Kenya has become home to hundreds of thousands of refugees since it gained independence in 1963. These refugees are typically fleeing violence in nearby countries. For instance, there are more than 300,000 Somali refugees in Kenya.

Kenya is also a host country for refugees as well as a source of emigrants. In the 1960s and 70s, Kenyans emigrated to the US, UK, Soviet Union, and Canada for study opportunities. In the 1980s and 90s, Kenya experienced economic and political problems that resulted in a further outpouring of Kenyan students and professionals who sought opportunities in the west and in southern Africa. Conversely, Kenya has become home to hundreds of thousands of refugees since it gained independence in 1963. These refugees are typically fleeing violence in nearby countries. For instance, there are more than 300,000 Somali refugees in Kenya.

Nairobi is the capital and largest city in Kenya, home to 3.3 million people and one of the largest cities in Africa. It lies in the southwest of the country in the highlands, at an elevation of 5,500 feet. Nairobi is home to thousands of businesses and more than100 major international companies and organizations. The city came to life in the late 1890s as a colonial railway settlement. While it is often mentioned as a jumping off point for safari-going foreigners, Nairobi is Kenya’s principal industrial center. Tourism is important, but its railways are the largest industrial employer, plus light manufacturing of beverages, cigarettes, and processed food.

A closer look at transforming healthcare by having well-trained professionals and the benefits to the communities over time

The quality of a healthcare facility is only as good as its healthcare providers. The fanciest equipment and size of staff cannot mask under-qualified workers – from doctors to nurses to technicians. Globally, 60 percent of the world’s deaths in health systems – including those arising from maternal and newborn complications – are due to poor-quality care. These dire consequences have the unfortunate effect of giving residents a negative view on healthcare, which in turn prevents people from participating in the healthcare system at all, let alone preventative care.

There are many forms of training that benefit healthcare professionals. For instance, in-service training, where workers are trained and discuss their work with their colleagues, has been shown to be indispensable for improving the quality of patient care. Simulators provide critical learning opportunities, providing professionals such as surgeons the closest experience to the real thing. Conventional in-class lectures and training are also beneficial, but nothing replaces hands-on experiential learning.

There are many forms of training that benefit healthcare professionals. For instance, in-service training, where workers are trained and discuss their work with their colleagues, has been shown to be indispensable for improving the quality of patient care. Simulators provide critical learning opportunities, providing professionals such as surgeons the closest experience to the real thing. Conventional in-class lectures and training are also beneficial, but nothing replaces hands-on experiential learning.

Unfortunately, there is a growing lack of experienced, well-trained healthcare workers in many areas of the world. Studies show that in developing countries there is a glaring lack of knowledge about how to diagnose and manage common diseases. Plus, there is a frightening lack of healthcare workers in these challenged areas. In Africa, there are 2.3 healthcare workers for 1,000 people, compared to 24.8 healthcare workers for 1,000 in the US. This translates into barely one percent of the world’s health workers caring for people who have 25 percent of the world’s diseases.

Part of the problem is that medical discoveries and technologies are unfolding at such a fast pace that it is hard to keep up with the changes. And governments in developing countries that succumb to corruption and misplaced allocation of resources do not always place healthcare high on the priority list. Whatever the reason, failing to adequately train healthcare workers leads those professionals to move on to other institutions and ultimately results in frustrated patients, higher costs, and deadly outcomes. On the other hand, there are numerous advantages to invest in continuous healthcare training: staff members who are highly skilled want to stay on board, the reputation of the facility is enhanced, and better patient outcomes are realized.

Part of the problem is that medical discoveries and technologies are unfolding at such a fast pace that it is hard to keep up with the changes. And governments in developing countries that succumb to corruption and misplaced allocation of resources do not always place healthcare high on the priority list. Whatever the reason, failing to adequately train healthcare workers leads those professionals to move on to other institutions and ultimately results in frustrated patients, higher costs, and deadly outcomes. On the other hand, there are numerous advantages to invest in continuous healthcare training: staff members who are highly skilled want to stay on board, the reputation of the facility is enhanced, and better patient outcomes are realized.

Source Materials

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ke.html

https://www.britannica.com/place/Nairobi

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5238493/

https://healthmanagement.org/c/healthmanagement/issuearticle/the-importance-of-continuous-education-in-healthcare

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2680393/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26255714_Shortage_of_Healthcare_Workers_in_Developing_Countries-Africa