Mission

Refugee Protection International’s (RPI) mission is to partner with local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and duty bearers to strengthen protection and self-reliance among urban refugees and internally displaced persons near conflict zones through interventions including, but not limited to, innovative housing solutions, civil and residency documentation, and emergency protection assistance.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

With an estimated 1.5 million Syrians having fled Syria, Lebanon now hosts the highest number of refugees per capita globally. Refugees comprise 30 percent of Lebanon’s population, which places enormous demands on its education system. In addition, 70 percent of Syrians born in Lebanon have not registered their birth with the Foreigners Registry, gravely complicating their access to services. The vast majority live in tents or similar temporary structures in small, dispersed informal settlements along the Syrian border. Back-breaking work in stone quarries is one of the main sources of income in the area.

With an estimated 1.5 million Syrians having fled Syria, Lebanon now hosts the highest number of refugees per capita globally. Refugees comprise 30 percent of Lebanon’s population, which places enormous demands on its education system. In addition, 70 percent of Syrians born in Lebanon have not registered their birth with the Foreigners Registry, gravely complicating their access to services. The vast majority live in tents or similar temporary structures in small, dispersed informal settlements along the Syrian border. Back-breaking work in stone quarries is one of the main sources of income in the area.

At least 270,000 Syrian children ages 3 – 18 years old are out of school in Lebanon. This unfortunate situation increases with age: 31 percent of primary school children ages 6 – 14 are out of school, 78 percent of those ages 15 – 17 and 89 percent of those ages 15 – 24. The most vulnerable refugees – those living in remote informal settlements, poor and single female-headed households, and those with disabilities and other learning challenges – are often most affected by barriers to education and civil documentation. Girls with a disability are even less likely to be enrolled. In 2018, 56 percent of Syrian children ages 6 – 14 with disabilities in Lebanon were out-of-school compared with 32 percent without disabilities. Being out-of-school and/or undocumented places refugee girls at greater risk of early marriage, child labor, and ineligibility for other services.

The lack of school access for refugees is more than a temporary challenge. Most refugees are unlikely to return to Syria soon due to ongoing violence and insecurity, devastation of public infrastructure and housing, fear of retribution and conscription, and brain drain among teachers and doctors. A mere 2 – 3 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon returned to Syria in 2018. This protracted displacement scenario makes the out-of-school crisis devastating to the self-reliance prospects of the Syrian refugee population in Lebanon.

Families who sought refuge in the remote tented settlements of Baalbek-El Hermel governorate have experienced the second highest out-of-school ratio among primary school-age Syrian children (43 percent) and the highest out-of-school ratio among youth ages 15 – 17 (14 percent) and 15 – 24 years old (7 percent) among Syrian refugees in all eight governorates of Lebanon. Limited mobility to register births that took place in Lebanon is part of the reason, as Syrians in this governorate have the second lowest legal residency ratio (14 percent of Syrians age 15 years or older). Indeed, 82 percent of Syrians in Baalbek-El Hermel born in Lebanon have not completed the four-step birth registration process compared to 70 percent of all Syrians born in Lebanon.

Families who sought refuge in the remote tented settlements of Baalbek-El Hermel governorate have experienced the second highest out-of-school ratio among primary school-age Syrian children (43 percent) and the highest out-of-school ratio among youth ages 15 – 17 (14 percent) and 15 – 24 years old (7 percent) among Syrian refugees in all eight governorates of Lebanon. Limited mobility to register births that took place in Lebanon is part of the reason, as Syrians in this governorate have the second lowest legal residency ratio (14 percent of Syrians age 15 years or older). Indeed, 82 percent of Syrians in Baalbek-El Hermel born in Lebanon have not completed the four-step birth registration process compared to 70 percent of all Syrians born in Lebanon.

The repercussions for refugee girls and single mothers in Arsal, Baalbek-El Hermel, are especially concerning. Among Syrian refugees in Lebanon, single mothers in Arsal are the least equipped financially to send their daughters to school or to afford registering their birth in Lebanon, a common prerequisite for school admission. On average, these female-headed Syrian households are the poorest of the poor. With just $1.63 per day to spend on a family of five, these single mothers can barely survive, let alone cover the cost of birth registration, transportation, and materials for children to access Lebanese schools. Here, 27 percent of refugee households are female led, earning just $49 per month. Plus, female refugees across all age groups have lower rates of legal residency status.

While there are nearly as many Syrian girls as boys enrolled in primary school in Lebanon, being out-of-school can place girls at greater risk of early marriage, which limits their return to school. Currently 27 percent of girls ages 15 – 19 are married. Marriage was reported as the primary reason for being out-of-school in Lebanon by 28 percent of Syrian girls ages 15 – 24, compared to 18 percent of same-age male respondents. By upper secondary school, fewer girls than boys are enrolled in school. Years of missed school reduce girls’ prospects of self-reliance.

While there are nearly as many Syrian girls as boys enrolled in primary school in Lebanon, being out-of-school can place girls at greater risk of early marriage, which limits their return to school. Currently 27 percent of girls ages 15 – 19 are married. Marriage was reported as the primary reason for being out-of-school in Lebanon by 28 percent of Syrian girls ages 15 – 24, compared to 18 percent of same-age male respondents. By upper secondary school, fewer girls than boys are enrolled in school. Years of missed school reduce girls’ prospects of self-reliance.

Despite the promising 5-year plan of the Lebanese Government, Reaching All Children with Education, many Syrian refugees remain unable to effectively access quality learning at Lebanese schools. Key obstacles include constraints on space and teaching resources, lack of birth registration documentation, cost of transportation and educational materials, language of instruction, and beliefs and capacity restraints to serving children with disabilities. Second shifts for Syrian refugees at Lebanese schools often end when it is dark, making some parents fear for their daughters’ well-being on the way home. Harassment and discrimination of refugee students by host communities is also a challenge. Lack of sufficient knowledge of English or French (the languages of instruction at most Lebanese schools) also prevents many refugee children from the predominantly Arabic-speaking Syrian community from effectively accessing the curriculum. Similar barriers hinder access to birth registration.

In addition, the Lebanese schools lack sufficient teacher training and resources to support effective learning in mainstream classrooms for children with special needs. Discriminatory admission policies, lack of inclusive curricula, and discriminatory fees and expenses have also been reported. Social norms and attitudes toward disability is another challenge. For the most part, teachers have not been trained in delivering inclusive education to children with other special needs, such as ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Social Communication Disorder, Speech and Language Delay, and generalized anxiety, among other learning profiles.

In addition, the Lebanese schools lack sufficient teacher training and resources to support effective learning in mainstream classrooms for children with special needs. Discriminatory admission policies, lack of inclusive curricula, and discriminatory fees and expenses have also been reported. Social norms and attitudes toward disability is another challenge. For the most part, teachers have not been trained in delivering inclusive education to children with other special needs, such as ADHD, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Social Communication Disorder, Speech and Language Delay, and generalized anxiety, among other learning profiles.

To facilitate access to education and other services, Lebanon has recently simplified the process for registering refugee births and marriages, but the process and eligibility criteria remain restrictive. Children born after Aug. 2, 2018 whose birth was not registered within one year must go to court to register their birth. Children whose parents lack a valid marriage certificate are unable to have their births registered. This is a problem, as 27 percent of Syrians in Lebanon have marriages that were not legally documented and 21 percent were married by an uncertified Sheikh.

Notwithstanding Lebanon’s easing of regulations on birth registration, many refugees are unaware of the above restrictions and the four-step registration process: 1. birth notification issued by doctor/midwife, 2. birth certificate registered by Mukhtar (mayor), 3. birth certificate issued by Nofous (civil office), and 4. birth certificate registered with the Foreigner’s Registry.  The top three reasons for not completing the fourth step include cost of registration fees and transportation (cited by 45 percent of respondents), lack of information on the process (21 percent), and lack of legal residency to move freely (12 percent). Freedom of movement is extremely limited in Arsal with its high number of security checkpoints.

The top three reasons for not completing the fourth step include cost of registration fees and transportation (cited by 45 percent of respondents), lack of information on the process (21 percent), and lack of legal residency to move freely (12 percent). Freedom of movement is extremely limited in Arsal with its high number of security checkpoints.

Effective access to inclusive, quality education and birth registration documentation is essential to Syrian refugees’ self-reliance and protection, particularly as safe, voluntary return to war-torn Syria is not a current reality for most.

The Project

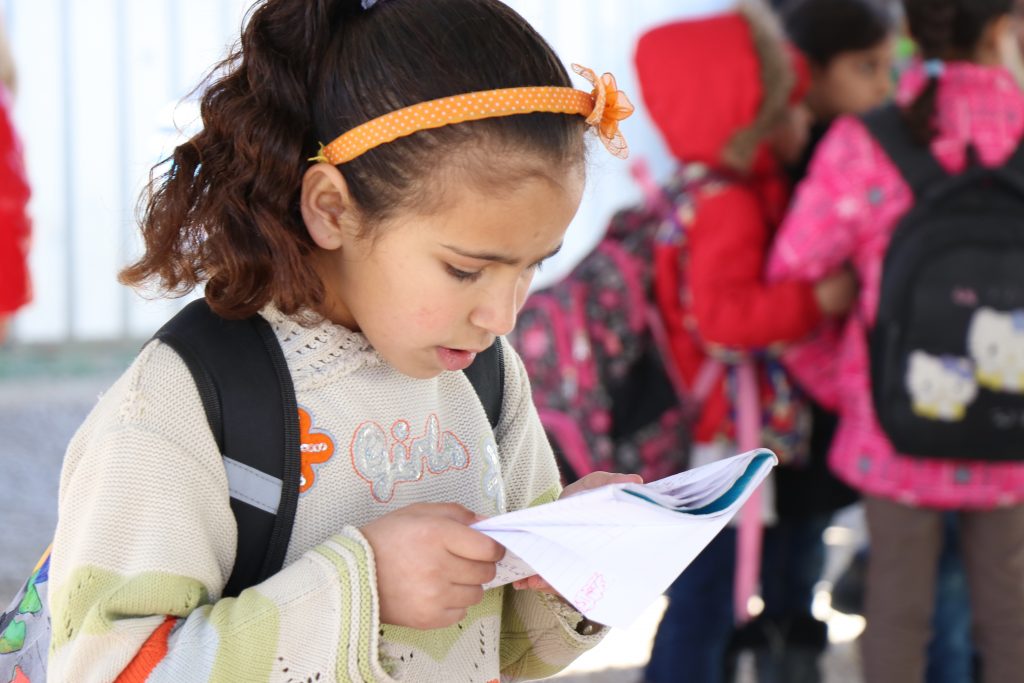

RPI aims to provide Syrian refugee girls in Arsal, Lebanon, a regulated, non-formal primary education and the opportunity to access birth registration documentation. Refugee women will be mobilized to support the education of girls, including those with disabilities, and school staff will receive training on how to support inclusive learning.

The three objectives of this project are to 1. help Syrian women register the birth of their daughters to improve school access, 2. provide free education to refugee girls at their settlements to overcome cost barriers to Lebanese schools, and 3. encourage families to educate girls, including those with disabilities, and help schools meet their needs.

This project follows a 5-pronged approach:

This project follows a 5-pronged approach:

- Birth registration information and case management – RPI’s local partner Union of Relief and Development Associations (URDA) will provide information and legal counseling sessions to 1,000 refugee women in 40 informal settlements, giving priority to single mothers, pregnant women, and vulnerable women of child-bearing age. The sessions will inform refugees of the importance of birth registration to accessing services and the four-step process to be followed to register birth certificates with the Foreigners Registry. Sessions will also inform refugees of eligibility criteria, requisite documentation and fees for the application process, and the locations to be visited.

At the end of the session, participants will receive the telephone number for the lawyer, who they may call to receive additional counseling. The lawyer will also meet with parents briefly directly after each group session to answer any immediate questions and to conduct interviews with those in need of further legal counselling and/or financial/logistical support in order to complete the birth registration process.

To make registration feasible for 155 of the most vulnerable girls of single mothers, RPI will cover the $100 birth registration fee, complete registration applications, and transport application materials to registration offices, including through security checkpoints when needed. At times, advocacy will be required to encourage disinclined administration officials to adhere to regulations and process the applications. To mitigate the risk of tension over beneficiary selection for this project component, criteria will be clearly explained during group information sessions.  Regulated non-formal primary school education – Building on a four-year non-formal education partnership with RPI, RPI’s local partner Multi Aid Programs will reopen three caravan schools to serve 300 Syrian girls in Arsal. MAPS will first meet with the target communities to explain selection criteria and encourage enrollment. Books and paper will be distributed to students. Classes will be taught in English (six per week), Arabic (six per week), math (five per week), science (two per week) and life skills (once per week). Life skills will focus on cultivating strong ethics and leadership skills.

Regulated non-formal primary school education – Building on a four-year non-formal education partnership with RPI, RPI’s local partner Multi Aid Programs will reopen three caravan schools to serve 300 Syrian girls in Arsal. MAPS will first meet with the target communities to explain selection criteria and encourage enrollment. Books and paper will be distributed to students. Classes will be taught in English (six per week), Arabic (six per week), math (five per week), science (two per week) and life skills (once per week). Life skills will focus on cultivating strong ethics and leadership skills.

In contrast to Lebanese schools, these caravan classrooms are within refugee settlements. Students need not pay for bus transportation and parents will not fear for their daughters’ protection on their way home from school in the dark because no travel beyond the settlement is required. Students will have free access to learning materials, psychosocial support, and the basic Lebanese curriculum in their native language Arabic. Students will be better prepared to pass their entrance exams to Lebanese secondary schools owing to rigorous academic work and intensive English classes. Their non-formal education is recognized thanks to a Memorandum of Understanding between MAPS and the Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education.

Psychosocial support will be provided using the Helping Hands program. Teachers have received training in this program since 2017 by Dr. Solfird Raknes, a Norwegian clinical psychologist. Teachers now have the tools to help students who have experienced trauma to develop their emotional literacy and social communication skills. Teachers have also been trained in assessing children’s psychological condition using a validated behavioral questionnaire. MAPS has partnered with the Art of Hope to learn how to support children with PTSD through art.

In addition, students will benefit from periodic medical screenings and referrals to MAPS health centers for treatment. Students in grades 4-6 will have access to classes in applied science, robotics and computer programming. Principals and teachers will inform students about personal, school and home hygiene practices. The teachers will conduct a periodic screening of students for hygiene and illness and refer cases that need treatment and follow-up Parent-teacher meetings will be held each semester to discuss the academic progress of the parents’ children.

In addition, students will benefit from periodic medical screenings and referrals to MAPS health centers for treatment. Students in grades 4-6 will have access to classes in applied science, robotics and computer programming. Principals and teachers will inform students about personal, school and home hygiene practices. The teachers will conduct a periodic screening of students for hygiene and illness and refer cases that need treatment and follow-up Parent-teacher meetings will be held each semester to discuss the academic progress of the parents’ children.- Engaging female teachers from the refugee community – RPI will hire 15 refugee women as teachers at the three schools, providing an estimated 75 members of their families with the indirect benefits of improved household income.

Community awareness campaigns by refugee schools – RPI will raise awareness among up to 1,500 community members (women and girls) on the importance of educating girls and children with disabilities (to encourage enrollment and retention), on best hygiene practices while in displacement. Through monthly awareness sessions at its schools, MAPS will discourage dropouts among older primary school-age girls by highlighting the long-term gains to self-reliance of avoiding early marriage. MAPS will also emphasize the right of children with disabilities to as inclusive an education as possible. These messages will be reinforced during parent-teacher conferences and the principal will visit the homes of students who are absent or have dropped out to encourage their return to school.

Community awareness campaigns by refugee schools – RPI will raise awareness among up to 1,500 community members (women and girls) on the importance of educating girls and children with disabilities (to encourage enrollment and retention), on best hygiene practices while in displacement. Through monthly awareness sessions at its schools, MAPS will discourage dropouts among older primary school-age girls by highlighting the long-term gains to self-reliance of avoiding early marriage. MAPS will also emphasize the right of children with disabilities to as inclusive an education as possible. These messages will be reinforced during parent-teacher conferences and the principal will visit the homes of students who are absent or have dropped out to encourage their return to school.- Improving teacher capacity to educate refugee girls with disabilities – S. and regional specialists will be invited to provide remote professional development support in special education and visual aids to three teachers to serve as school focal points. These focal points will be trained on how to provide group pull-out services to children with special needs, how to instruct teachers to make modifications and adaptations within mainstream classrooms, and how to instruct refugee volunteers to serve as in-class aides.

Direct Impact: 2,670, Indirect Impact: 320

UN Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- How do you think educating these children benefit the broader community?

- What special skills might a teacher need with refugee children?

- Why is it important that the teachers themselves are refugees?

How the Grant Will be Used

NOTE: During these unprecedented times of COVID-19, Dining for Women has adapted grant funding and offered flexibility to grantees in the timeline, budgets and execution of their projects. These adjustments will be reported in the grantee reports.

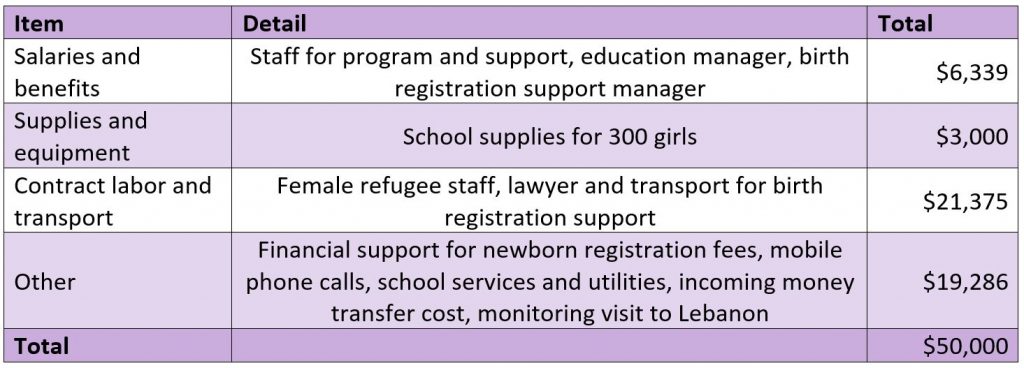

DFW’s grant of $50,000 will be used for the following:

Why We Love This Project/Organization

Presently, Lebanon hosts 1.5 million Syrian refugees who are facing protracted displacement and statelessness. By helping women and girls with documentation, birth registration, schooling, and access to services, these populations will have more stability in their lives and an opportunity to work towards a better future.

Evidence of Success

RPI’s model was recognized by the New England International Donors Giving Circle on Refugees in its 2019 grant awards. The American Securities Foundation featured RPI’s collaboration with refugee-led partner Multi Aid Programs (MAPS) on refugee education in Lebanon in their 2018 and 2017 giving back reports. RPI was featured for three years in MathWorks Social Mission year-end campaign and the Swedish Women’s Educational Association yuletide fair in Boston.

Voices of the Girls

“I am a teacher. I teach Syrian refugee children in their informal settlements. I’m working with this target group because they will be the cornerstone of Syria. We’re teaching young children so that they will be empowered to rebuild their country with knowledge and hope. I’m so glad that I have this chance to work with them. They make me feel stronger and more optimistic that Syria will soon recover to be better, hopefully.”

“I am a teacher. I teach Syrian refugee children in their informal settlements. I’m working with this target group because they will be the cornerstone of Syria. We’re teaching young children so that they will be empowered to rebuild their country with knowledge and hope. I’m so glad that I have this chance to work with them. They make me feel stronger and more optimistic that Syria will soon recover to be better, hopefully.”

- Female refugee teacher in Bekaa Valley.

“My name is Rabi’a and I am 7 years old. I was born with a decreased level of oxygen in my brain (Cerebral Hypoxia). This led me to have a deformity in both my legs. I am now studying in the Al Amal Teaching Centers so that I can become a teacher when I grow up. I want the children that I will teach to grow up and become doctors so that they can heal people that have my disease.”

- Young Syrian girl in Bekaa Valley.

“My name is Shifa, 7 years old. When I grow up, I’ll be a doctor to help all people in need.”

- Female Syrian refugee student in Bekaa Valley

“I’m grateful to God. My children were not registered and lacked any official documents. Now they are officially registered and able to join schools and benefit from other services. Everything is okay now and my children possess all the necessary documents to lead a normal life.”

- Shared by Syrian refugee mother with RPI’s local community partner, the Union of Relief & Development Associations (URDA)

“I am from Syria. I gave birth to my daughter a month ago. She wasn’t registered. I managed to register my daughter thanks to URDA and RPI, which offered to handle all the necessary expenses.”

- Shared by Syrian refugee mother with URDA

About the Organization

Refugee Protection International was founded in 2015 by Jennifer (Zimmermann) Hill, President and Executive Director, in collaboration with three other board directors, all of whom remain on the board today.

RPI focuses on refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) who have fled armed conflicts but remain in their country of origin or frontline host countries. RPI prioritizes women and children displaced to urban areas, where traditional aid is often limited or inadequately tailored. In justifiable cases, they also support aid in rural makeshift settlements. RIP’s refugee-led partners benefit from visibility on their website and conversations with giving partners. They also benefit from technical support with project design, proposal writing, and networking with specialists. RPI’s vision is for partners to access external funding more readily and for their projects to better meet refugee self-reliance needs.

RPI focuses on refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) who have fled armed conflicts but remain in their country of origin or frontline host countries. RPI prioritizes women and children displaced to urban areas, where traditional aid is often limited or inadequately tailored. In justifiable cases, they also support aid in rural makeshift settlements. RIP’s refugee-led partners benefit from visibility on their website and conversations with giving partners. They also benefit from technical support with project design, proposal writing, and networking with specialists. RPI’s vision is for partners to access external funding more readily and for their projects to better meet refugee self-reliance needs.

With a record 71 million persons displaced globally, RPI promotes self-reliance and protection among conflict-displaced civilians using an efficient, scalable, and locally driven humanitarian model. They assist inspiring refugee-led nonprofits in the Middle East with project design, technical and logistic needs, grants, and monitoring to better serve urban refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) in 3 key program areas: protection and self-reliance, education and health, and shelter.

Together with their refugee-led partners, RPI has improved access to education, health, shelter, and protection for more than 44,751 refugees and IDPs in the Middle East, and rehabilitated medical infrastructure to serve an estimated 56,412 civilians annually. The personal impact stories shared are humbling and inspiring.

Together with their refugee-led partners, RPI has improved access to education, health, shelter, and protection for more than 44,751 refugees and IDPs in the Middle East, and rehabilitated medical infrastructure to serve an estimated 56,412 civilians annually. The personal impact stories shared are humbling and inspiring.

In Eastern Ghouta, Syria, 12-year old orphan Abdul-Aziz refused to talk after losing his entire family in an air raid. Pulled from the rubble, Abdul-Aziz was invited to participate in an RPI-supported psychosocial support program held underground for safety. With the dedicated attention of local NGO staff, he emerged from seclusion and re-engaged with his peers. A total of 180 children participated, many having hidden from aerial attacks in their families’ basements without light or sanitation for weeks on end.

Ali Jumaa, his wife, children, and extended female relatives had displaced six times to avoid heavy shelling before fleeing to an unfinished one-room apartment exposed to the winter elements in Idlib. In exchange for housing repairs conducted by Basmeh and Zeitooneh under a project co-designed by RPI, a new landlord provided one year of rent-free adequate housing, enabling this family to stay warm and afford schooling.

RPI’s model amplifies humanitarian impact in the refugee space in three ways. First, they support the local capacity of vetted refugee-led nonprofits on the frontlines of war, allowing them to lead efforts where most of the displaced live. Second, they strengthen project design by bridging silos and integrating gender analysis, public-private-civil society partnerships, and a rights-based urban approach. Third, through collaboration they allocate 93 – 95 percent of expenses toward programming. RPI currently partners primarily with the following local NGOs: Multi Aid Programs, Union of Relief and Development Associations, Basmeh and Zeitooneh, Kids Paradise, Olive Branch, and the Sustainable International Medical Relief Organization.

RPI’s model amplifies humanitarian impact in the refugee space in three ways. First, they support the local capacity of vetted refugee-led nonprofits on the frontlines of war, allowing them to lead efforts where most of the displaced live. Second, they strengthen project design by bridging silos and integrating gender analysis, public-private-civil society partnerships, and a rights-based urban approach. Third, through collaboration they allocate 93 – 95 percent of expenses toward programming. RPI currently partners primarily with the following local NGOs: Multi Aid Programs, Union of Relief and Development Associations, Basmeh and Zeitooneh, Kids Paradise, Olive Branch, and the Sustainable International Medical Relief Organization.

Where They Work

The smallest country in continental Asia, Lebanon sits between Israel and Syria on the Mediterranean Sea. It is home to 5.5 million Arabs, of whom 61 percent are Muslim and 34 percent are Christian. The majority live near the coast in and around the capital city of Beirut, where they enjoy mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers.

In theory, Lebanon is a free-market economy. However, although the government does not restrict foreign investment, there is considerable corruption, complex procedures, high taxes, and other roadblocks. Wars have damaged the lives, livelihoods, and economic standing of the Lebanese. The civil war that raged from 1975 to 1990 damaged Lebanon’s economic infrastructure, cutting the national output by half and unseating Lebanon as the Middle Eastern banking hub. After the war, Lebanon borrowed to rebuild. Unfortunately, this ended up adding a huge debt burden to the country. The conflict with Syria resulted in nearly a million registered and 300,000 unregistered Syrian refugees arriving in Lebanon, which has greatly increased social tensions and increased competition for low-skill jobs and public services.

In theory, Lebanon is a free-market economy. However, although the government does not restrict foreign investment, there is considerable corruption, complex procedures, high taxes, and other roadblocks. Wars have damaged the lives, livelihoods, and economic standing of the Lebanese. The civil war that raged from 1975 to 1990 damaged Lebanon’s economic infrastructure, cutting the national output by half and unseating Lebanon as the Middle Eastern banking hub. After the war, Lebanon borrowed to rebuild. Unfortunately, this ended up adding a huge debt burden to the country. The conflict with Syria resulted in nearly a million registered and 300,000 unregistered Syrian refugees arriving in Lebanon, which has greatly increased social tensions and increased competition for low-skill jobs and public services.

Regardless of the crisis with Syria, Lebanon faces several challenges. These include weak infrastructure, poor service access, institutionalized corruption, and lots of red tape. As a result, almost 29 percent of Lebanese live below the poverty line.

Arsal is 77 miles northeast of Beirut, an area known for hand-made carpets and a source of good water. The Lebanese government bulldozed many refugee huts in 2019. According to the UNHCR, the resolution affected 2,300 shelters in 17 camps and up to 15,000 people, of whom about half were children. As a result, the humanitarian situation in Arsal has deteriorated dramatically.

A closer look at the schooling of refugee children and their long-term prognosis for economic empowerment

There are approximately 26 million refugees in the world; around half are under age 18. More than half of school-age refugee children do not receive any kind of education. Consider the comparisons: 63 percent of refugee children attend primary school compared to 91 percent globally. Only 24 percent of teen refugees get a secondary education compared to 84 percent globally. A mere 3 percent of refugee children go on to higher education compared to 37 percent globally. The reasons for these disparities vary, but often include low absorption capacity in local schools, the distance a refugee child must travel to attend school, and numerous social, cultural, and economic factors.

The UNHCR estimates that refugees miss three to four years of schooling due to forced displacement. The refugee children who do attend school show up with grave histories and scars. Many watched their homes be destroyed and family members killed. They have witnessed unthinkable violence. Some have disabilities, were child soldiers themselves, or have survived sexual abuse.

The UNHCR estimates that refugees miss three to four years of schooling due to forced displacement. The refugee children who do attend school show up with grave histories and scars. Many watched their homes be destroyed and family members killed. They have witnessed unthinkable violence. Some have disabilities, were child soldiers themselves, or have survived sexual abuse.

Yet despite these profound challenges, gaining an education can have a transformative effect on child refugees – just as it does for children around the world. It can provide the foundation for future growth and learning, an opportunity to learn about the world around them. In addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic, it can teach children about basic health care and hygiene, human rights, and who can provide assistance when needed. Gaining an education helps children feel more independent and hopeful. Some countries have developed strategies and systems for integrating refugees into their classrooms, while others remain challenged.

Child refugees who do not receive an education fall through much larger cracks than other children. Without this foundation – and living with deep emotional scars – they become at risk for a host of unfortunate outcomes, including child trafficking. Without intervention, their futures and economic outlook are extremely bleak.

Source Materials

https://www.unhcr.org/neu/28737-refugee-education-in-crisis-more-than-half-of-the-worlds-school-age-refugee-children-do-not-get-an-education.html

https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/starting-out.html

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/le.html

https://www.npr.org/2019/06/22/733408450/forced-to-demolish-their-own-homes-syrian-refugees-in-lebanon-seek-new-shelter