Mission

Etta Projects collaborates with communities, creating sustainable solutions to improve health, sanitation and clean water.

Life Challenges of the Women Served

In Bolivia, the poorest country in South America, 43 percent of the country’s 10 million residents live in poverty. In rural areas, the number rises to 63 percent. Nonexistent water and sanitation systems compound the issue in rural eastern Bolivia, where only 10 percent of the population has toilets, and waterborne illnesses are the number one cause of death. Nine out of 10 people use pit latrines or open air, which often overflow during the rainy months, spreading human waste and leading to diarrhea and other parasitic infections. The risk of contracting an infectious disease such as hepatitis A, malaria or yellow fever is also high.

Unfortunately, Bolivia’s healthcare system can neither prevent nor effectively treat these and other common medical issues because it is grossly inadequate and often inaccessible. Poor infrastructure, cultural attitudes and lack of access to information all contribute to negative but preventable health outcomes. For instance, an area with over 1,000 residents may have just one physician and one nurse. Outside of weekday hours, there is no emergency or urgent care. Roads flood in the rainy season and transportation is often unreliable during the dry season, forcing villagers to walk to health centers. In addition, the indigenous people, who comprise 20 percent of the population, may not trust modern medicine or those who treat them, due to prejudice and a lack of respect displayed by medical personnel.

Unfortunately, Bolivia’s healthcare system can neither prevent nor effectively treat these and other common medical issues because it is grossly inadequate and often inaccessible. Poor infrastructure, cultural attitudes and lack of access to information all contribute to negative but preventable health outcomes. For instance, an area with over 1,000 residents may have just one physician and one nurse. Outside of weekday hours, there is no emergency or urgent care. Roads flood in the rainy season and transportation is often unreliable during the dry season, forcing villagers to walk to health centers. In addition, the indigenous people, who comprise 20 percent of the population, may not trust modern medicine or those who treat them, due to prejudice and a lack of respect displayed by medical personnel.

The situation is particularly grim for Bolivian women, who endure horrific treatment on top of the unsanitary conditions. Bolivia ranks first in Latin America for violence against women and second for sexual violence. Women in rural Bolivia suffer gender inequality and discrimination, remaining in abusive relationships and in isolated communities with little emotional or social support. Seven out of 10 suffer psychological and physical violence in the home. These women are unaware of their rights and believe that men can continue to physically or psychologically mistreat them. Victims cannot reach their personal or professional goals, which, coupled with poor sanitation and little medical support, fosters generations of abuse, negativity and hopelessness. In general, Bolivian women disproportionately encounter disparities in health services and education, especially with respect to reproductive rights. Sexual and reproductive health is still a taboo subject in these communities, and young people are poorly informed on sexual and reproductive issues.

The Project

The Etta Projects Health Promotion Program for Bolivian Women increases educational opportunities and leadership roles for participants, improves village health, and seeks to reduce violence against women and girls. Health Promoters (HPs) learn how to educate and care for their fellow villagers, participate in planning meetings, and provide public health data to local authorities. They learn a skill that they can teach to others, thus offering the potential of enhanced health for future generations. Children, who often attend training sessions with their mothers, learn and see their mothers in a different light. The program has the ability to alter traditional stereotypes that exist for rural women and girls. However, in a patriarchal society like Bolivia, women who quickly ascend to leadership positions are frequently the subject of violence and marginalization. In response, the program allows time not only for change on the part of the women, but also positive change and acceptance in their villages, marriages and families.

The Etta Projects Health Promotion Program for Bolivian Women increases educational opportunities and leadership roles for participants, improves village health, and seeks to reduce violence against women and girls. Health Promoters (HPs) learn how to educate and care for their fellow villagers, participate in planning meetings, and provide public health data to local authorities. They learn a skill that they can teach to others, thus offering the potential of enhanced health for future generations. Children, who often attend training sessions with their mothers, learn and see their mothers in a different light. The program has the ability to alter traditional stereotypes that exist for rural women and girls. However, in a patriarchal society like Bolivia, women who quickly ascend to leadership positions are frequently the subject of violence and marginalization. In response, the program allows time not only for change on the part of the women, but also positive change and acceptance in their villages, marriages and families.

Etta Projects (EP) will train 50 local villagers from 11 communities to become Health Promoters. These individuals, 95 percent of whom are women ages 18 – 40, will be chosen by community members by vote. Over the course of 80 training sessions (400 hours), participants will forge bonds with local doctors and traditional healers as they learn.

During the first year of training, HPs in the communities will provide greater access to information about health services and measures to improve the health of families in the community. Their primary care training will prepare them to respond in medical emergencies and treat recurrent common diseases. They will use a health kit for emergency care and to treat issues such as dehydration, stomach upset, headaches and minor injury, and they will be able to provide guidance on preventive measures, hygiene and sanitation. Also in their first year, and throughout their training, women and adolescents will begin to participate in community health meetings to voice their needs, report any situation where rights – primarily sexual and reproductive rights – are being compromised or abused and how to be advocates against physical violence.

During the first year of training, HPs in the communities will provide greater access to information about health services and measures to improve the health of families in the community. Their primary care training will prepare them to respond in medical emergencies and treat recurrent common diseases. They will use a health kit for emergency care and to treat issues such as dehydration, stomach upset, headaches and minor injury, and they will be able to provide guidance on preventive measures, hygiene and sanitation. Also in their first year, and throughout their training, women and adolescents will begin to participate in community health meetings to voice their needs, report any situation where rights – primarily sexual and reproductive rights – are being compromised or abused and how to be advocates against physical violence.

In their second year of training, participants learn about gender equality and how to improve access to information about sexual and reproductive health issues and contraception. HPs will conduct practicums, visit clinics and learn about sexual and reproductive rights, healthy birthing techniques and contraceptive options. HPs will work with classes of secondary school students teaching adolescents about their rights, abuse and how to access information to improve their life plans. All health kits will be enhanced with contraceptives and more advanced medications and equipment as HPs’ skills increase.

Overall, HPs learn basic first aid, sexual and reproductive health, midwifery skills, wound care and suturing, administration of vaccinations and antibiotics, basic life-saving, public speaking, leadership training, public health training in disease prevention and hygiene. This two-year model effectively promotes behavior change, self-esteem building and leadership skills among participants. HPs will become fluent in the specific health needs of children, adolescents, adults and elders. They will also learn more about their rights, current Bolivian policy and steps they can take to provide support and resources for issues related to violence in the family and community.

The project will take place in 11 villages in the Saavedra region, home to 5,361 residents.

Direct beneficiaries: 50 (all in their second year of training)

Indirect beneficiaries: 5,361

Sustainable Development Goals

![]()

![]()

Questions for Discussion

- Why is it important for Bolivia’s indigenous populations to have a voice in medical treatment?

- How might this program change rural Bolivian society?

- How could the role of Health Promoters influence attitudes about violence against women?

How the Grant Will be Used

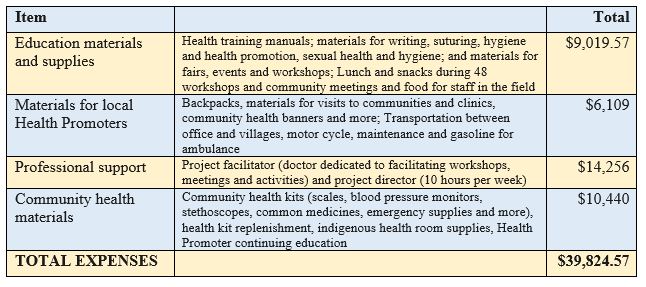

DFW’s grant of $39,824.57 over one year will cover the second year of the two-year training program for 50 Health Promoters. This will cover all educational workshop materials, office supplies and equipment, food, professional support, transportation and community health materials.

Why We Love This Project/Organization

We love this project because it enhances health and education, offers leadership roles for women, alters stereotypes for rural Bolivian women and girls and potentially reduces domestic abuse.

Evidence of Success

Studies show that the provision of safe water coupled with proper sanitation facilities can reduce deaths from diarrhea and water-related illnesses by 65 percent and improve overall childhood mortality by 55 percent. Since its inception, Etta Projects has enhanced the lives of over 64,500 rural Bolivians by providing improvements in the following areas:

- Health – Over 100 community leaders, 95 percent of whom are women, have beentrained in health promotion in 19 communities. These individuals possess the tools, skills and knowledge to become certified HPs, serving more than 7,500 people in 22 communities. These villagers provide many important health services and educate their communities on disease prevention, family planning, nutrition and child and adolescent health. EP has improved health care service in seven hospitals and health centers by providing medical equipment to isolated areas. In addition, EP has created one of Bolivia’s first Domestic Violence Prevention programs, and designed a program to help women bring back indigenous herbal medicine as a legitimate and affordable treatment for many ailments.

- Water quality – EP has developed water distribution systems specifically designed to meet the needs of individual villages. Families must assist in the manual labor and contribute financially to the cost of materials necessary for their own domestic connection, while water management committees are created by local elections.

- Sanitation – Seventeen communities and 380 families now have environmentally sound sanitation systems, thanks to the construction of more than 380 dry-ecological composting latrines that replaced shallow pit latrines or open defecation. Through training, families now enjoy improved hygienic bathroom habits and facilities, hand-washing and safe water practices. This has resulted in fewer water-related illnesses such as intestinal parasites, diarrhea, and scabies.

- Education – In addition to the in-depth training for rural Bolivians, EP conducts the It Starts Here, Now program for US students. To date, approximately 600 students have become educated on issues related to global poverty.

Voices of the Girls

“I am 30 years old and I have always dedicated myself to taking care of my family. I take care of the children and the house, and sometimes I help my husband in the fields. I feel sad because I can’t help cover the costs of our household economically, since I don’t have a job. Previously there was a course for health promoters, but I had to stop attending because I got sick. Now that there is another opportunity to learn I am definitely not going to miss out. I want to learn about nursing so that I can help my family, care better for my children and the baby that I’m expecting. I’ll also be able to help my community, because we live in a little town that is far from anything else, and when somebody gets sick there is nobody there to help them. The health center is 15 kilometers away and it is not open in the afternoons or weekends. Sometimes the only transportation is a tractor or a  motorcycle, and they have to go all the way to Montero to see a doctor. Besides, if I learn how to clean wounds, change dressings, or give shots I can charge a few bolivianos for my work. In that way I can contribute some money to my family. We are poor, my house is made of mud and palm leaves. I hope that one day I have my own first aid kit so that I can sell medication – right now there isn’t even a place to buy simple medications in our town. And with everything I do I will be a good example to my daughters, because they are women, and I want them to study something, and not feel limited to be a home maker like me.”

motorcycle, and they have to go all the way to Montero to see a doctor. Besides, if I learn how to clean wounds, change dressings, or give shots I can charge a few bolivianos for my work. In that way I can contribute some money to my family. We are poor, my house is made of mud and palm leaves. I hope that one day I have my own first aid kit so that I can sell medication – right now there isn’t even a place to buy simple medications in our town. And with everything I do I will be a good example to my daughters, because they are women, and I want them to study something, and not feel limited to be a home maker like me.”

–Carmen, Lote Hoyos community member

“Before I became a HP, I spent all my time in the house or in the sugar cane fields doing heavy labor. Now, I am studying and learning and my kids see me as an example. I want them to dream, to study, to reach their goals. My husband is learning to accept my independence which is hard in our very traditional culture. He’s still working on it! As a community HP, I delivered a baby in the ambulance at 11 p.m. one night! There were no doctors or medical staff at the clinic, and the ambulance driver didn’t know how to deliver a baby. He drove to my house and said ‘Someone needs you; I can’t find a doctor and I don’t know if I can get this mom to the hospital in time.’ Who knows what they would have done without me!”

–Marta, Bolivian mother and Health Promoter who went on to become a nurse

About the Organization

Etta Projects was created in 2003 by the Turner/Nixon families to honor the short life and meaningful legacy of Etta Turner, who died in a bus accident in 2002 while in Bolivia as an exchange student. Wise beyond her years, Etta believed in the power of the individual to effect meaningful change. Founder Pennye Nixon, Etta’s mother, was a Child, Family and Marriage Therapist before starting Etta Projects. In 2009, she was awarded the RESULTS Kitsap Peninsula Global Humanitarian Award for her work with global poverty issues. In 2008, she was awarded the International Woman of the Year Award by the city of Montero, Bolivia. Her goal is to help build communities where everyone can be safe and healthy.

Where They Work

EP serves women and families in rural eastern Bolivia who live without adequate water, sanitation and access to health care. Bolivia ranks at or near the bottom among Latin American countries in several areas of health and development, including poverty, education, fertility, malnutrition, mortality and life expectancy. Public education is poor, and educational opportunities are unevenly distributed, with girls and indigenous and rural children less likely to be literate or to complete primary school. Child labor is a reality for a quarter of children ages 5 – 14. Lack of education and family planning services results in Bolivia’s fertility rate of a little under three children per woman. As of 2012, 42 percent of the population was under the age of 19.

EP serves women and families in rural eastern Bolivia who live without adequate water, sanitation and access to health care. Bolivia ranks at or near the bottom among Latin American countries in several areas of health and development, including poverty, education, fertility, malnutrition, mortality and life expectancy. Public education is poor, and educational opportunities are unevenly distributed, with girls and indigenous and rural children less likely to be literate or to complete primary school. Child labor is a reality for a quarter of children ages 5 – 14. Lack of education and family planning services results in Bolivia’s fertility rate of a little under three children per woman. As of 2012, 42 percent of the population was under the age of 19.

A Closer Look at Poverty and Health

Poverty and poor health are inextricably linked, forming an unforgiving cycle: poverty increases the odds of ill health, and ill health traps individuals into poverty. Today, 1.2 billion people live in extreme poverty, or on less than $1 per day. A billion of these individuals suffer from diseases and disorders that can cause severe pain, life-long disabilities, or even death. Around the world, the list of diseases associated with poverty is familiar and tragic, since many are preventable, including HIV and tuberculosis. Women bear a disproportionate brunt of poverty, with higher rates of maternal and child mortality. Diarrhea, malaria and pneumonia account for nearly half of all child deaths globally.

The inability to afford life’s most basic necessities forces people to live in unhealthy environments, such as those found in rural eastern Bolivia, without clean water, adequate sanitation, healthy food or decent shelter. When the inevitable illness strikes, the fallout is often life-altering. If available, the cost of treatment may force families to sell their property, send their children to work instead of school, or become beggars. The most marginalized groups, including women and indigenous communities, may be faced with horrific choices, such as choosing to feed their children instead of themselves.

The inability to afford life’s most basic necessities forces people to live in unhealthy environments, such as those found in rural eastern Bolivia, without clean water, adequate sanitation, healthy food or decent shelter. When the inevitable illness strikes, the fallout is often life-altering. If available, the cost of treatment may force families to sell their property, send their children to work instead of school, or become beggars. The most marginalized groups, including women and indigenous communities, may be faced with horrific choices, such as choosing to feed their children instead of themselves.

Regardless of location, the root causes of poverty are typically political, social and economic inequalities. Such is the case in Bolivia, where income inequality is the highest in Latin America and among the highest in the world. The poverty-health connection becomes even more pronounced where war or other conflicts exist. In these areas, healthcare systems often collapse and medical equipment runs out, adding yet another impediment to a situation that already feels hopeless.

Source Materials

http://www.who.int/hdp/poverty/en/

CIA World Factbook

2014, UNICEF in Bolivia, UNICEF